Tag: writing

Pen to paper

25 October 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

Writing is ancient: the act of taking a stylus, a quill or a pen into one’s hand still feels powerful. Will we find a way of scrawling in space, to mark our individuality, wonders Teemu Manninen

It was my vacation, and I wanted to catch up on some fun writing projects, but because I didn’t want to depend on my devices (would we have wifi? would the batteries last?) or carry around too much extra stuff I bought a red notebook and wrote in black ink on white paper while sitting in cafes and restaurants with my wife.

Writing by hand got me – surprise – to thinking about handwriting in general. Etymologically, ‘writing’, from Old English writan, means scratching, drawing, tearing. In the original Hebrew, God does not simply fashion humans out of clay, he writes them: his word is his image, giving life to the letter of his meaning, the human being.

Writing is violence. It brings about vivid change in the matter of the world: in the age of clay tablets, the stylus was a carving instrument. During the age of ink, cutting the tip of the quill was, if we believe the early Renaissance manuals of handwriting, as precise and violent an act as cutting someone’s head off. More…

Figuring out father

18 October 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

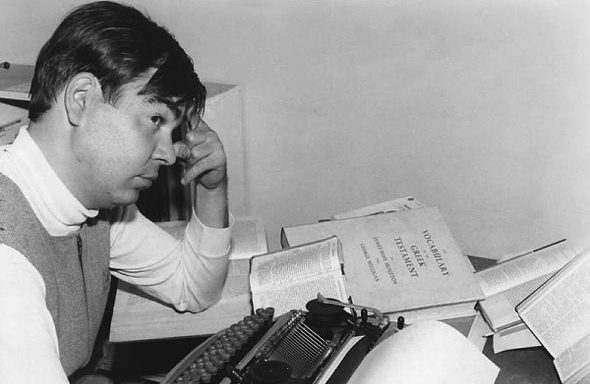

Pentti Saarikoski (1960s). Photo: Otava/Nikolai Naumoff

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) jotted in one of his journals: ‘I have never cared for relatives.’ Thirty years after his death one of his five children set out to find out what his father was like – by reading almost all he left behind in writing; these comments by Saska Saarikoski are from his Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012), an annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts

Pentti Saarikoski died when I was 19. I remember complaining to my mother that I had not yet even got to know my dad. My mother answered: You’ve got plenty of time, the real Pentti is to be found in his books. She did not know how right she was, for she meant Pentti’s published books, not knowing what a mountain of texts awaited its readers in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society. Pentti had written everything down in his diaries.

I read Nuoruuden päiväkirjat (‘Youthful diaries’), published soon after Pentti’s death in 1983, as soon as they were published, but when his Prague, Drunkard’s and Convalescent’s Diaries appeared around the millennium, they went straight on to my library shelf. I was not terribly interested in the ramblings of Pentti’s alcoholic years.

It could be that my reluctance was influenced by the cool attitude I had adopted from early on in relation to my father. Other people were welcome to consider him a genius; for me, he was a father who did not telephone, write or come to see my football matches. I didn’t call him, either; for me, it was a father’s job. More…

Indifference under the axe

9 March 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

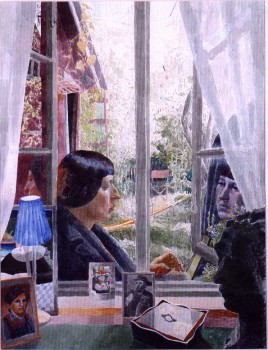

In the forest: an illustration by Leena Krohn for her book, Sfinksi vai robotti (Sphinx or robot, 1999)

The original virtual reality resides within ourselves, in our brains; the virtual reality of the Internet is but a simulation. In this essay, Leena Krohn takes a look at the ‘shared dreams’ of literature – a virtual, open cosmos, accessible to anyone, without a password

How can we see what does not yet exist? Literature – specifically the genre termed science fiction or fantasy literature, or sometimes magic realism – is a tool we can use to disperse or make holes in the mists that obscure our vision of the future.

A book is a harbinger of things to come. Sometimes it predicts future events; even more often it serves as a warning. Many of the direst visions of science fiction have already come true. Big Brother and the Ministry of Truth are watching over even greater territories than in Orwell’s Oceania of 1984. More…

Life is

16 February 2012 | Letter from the Editors

Helsinki silhouette. Photo: Valtteri Hirvonen, Eriksson&Company / World Design Capital Helsinki, 2011

Where is Books from Finland located?

In the old days, the answer was simple, although not unambiguous. Books came from its office in central Helsinki; it was written in various locations in Finland and abroad, and translated mainly in England and the United States; and it was published in the small town of Vammala, about 200 kilometres north of Helsinki.

It spread, in multiple paper copies, to readers throughout the world, to find its place on desks, on bedside tables, in briefcases and handbags, propping up table-legs or holding doors open – in London, England, Connecticut, New England, with a few in Paris, France, and Paris, Texas, maybe. More…

A light shining

28 July 2011 | Essays, Non-fiction

Portrait of the author: Leena Krohn, watercolour by Marjatta Hanhijoki (1998, WSOY)

In many of Leena Krohn’s books metamorphosis and paradox are central. In this article she takes a look at her own history of reading and writing, which to her are ‘the most human of metamorphoses’. Her first book, Vihreä vallankumous (‘The green revolution’, 1970), was for children; what, if anything, makes writing for children different from writing for adults?

Extracts from an essay published in Luovuuden lähteillä. Lasten- ja nuortenkirjailijat kertovat (‘At the sources of creativity. Writings by authors of books for children and young people’, edited by Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen; The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature & BTJ Kustannus, 2010)

What is writing? What is reading? I can still remember clearly the moment when, at the age of five, I saw signs become meanings. I had just woken up and taken down a book my mother had left on top of the chest of drawers, having read to us from it the previous day. It was Pilvihepo (‘The cloud-horse’) by Edith Unnerstad. I opened the book and as my eyes travelled along the lines, I understood what I saw. It was a second awakening, a moment of sudden realisation. I count that morning as one of the most significant of my life.

Learning to read lights up books. The dumb begin to speak. The dead come to life. The black letters look the same as they did before, and yet the change is thrilling. Reading and writing are among the most human of metamorphoses. More…

Face, book

23 June 2011 | Letter from the Editors

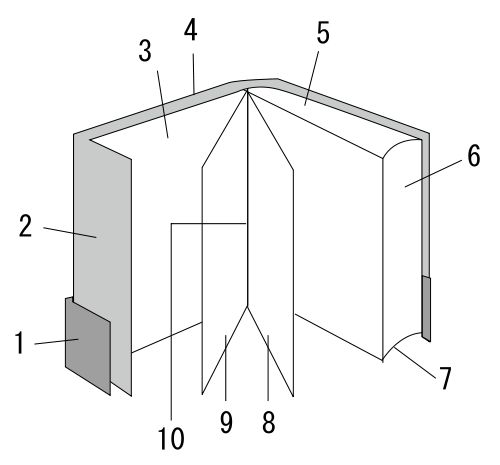

What are books made of? Picture: Wikipedia

‘The worst of all is if the writer forgets writing and starts turning out books.’

This thought is from the poet Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen’s introductory talk at the Lahti International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE), which took place at Messilä Manor between 19 and 22 June. ‘There’s too much talk of the stunting of the book’s lifespan and the economic life of the publishers,’ she continues. A writer ‘must not forget that he or she is responsible to the work of art, nobody else, not even the readers.’

Today, book publishers are responsible to capital and productivity, and a work of literature resembles a product with an invisible best-before marker. Is its life a couple of months, like ice cream? Books delivered to the shop in September are already old-hat in February, and are best put on sale. More…

Head in a cloud

27 May 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

Thinking, reading, writing, buying… Teemu Manninen explores the new freedoms, literal and poetic, offered by cloud computing, where what you can do is no longer limited by what you happen to have on your computer

High in the sky: cumulus clouds. Photo: Michael Jastremski, Wikimedia

I’m sitting in a rocking chair on the porch of a cottage by a lake. My fingers tap and slide on the surface of a black glass panel, a kind of instrument used in the composing of literature. Each tap equals a letter, a series of taps equals a word, a symphony of taps becomes a paragraph, a paragraph an essay.

The glass panel remembers these letters and words and the writings they become, and knows them by their names, but it could also record anything I see or hear. I could even talk to it and it would understand my commands, as if some nether spirit were captured inside, a magic genie slaved to do my bidding. More…

The pirate’s friend

11 March 2011 | Articles, Non-fiction

Intellectual property was hot stuff half a millennium ago, and not much has changed: Teemu Manninen takes a look at piracy and mercenaries in the age of electronic books

Sir Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554–1628) by Edmund Lodge. Photo: Wikimedia

In November 1586 Fulke Greville (later 1st Baron Brooke) sent Queen Elizabeth’s spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham a letter complaining about some ‘mercenary printers’‘ plans to print the romance novel Arcadia written by his friend (and Walsingham’s son-in-law) Sir Philip Sidney, who had died that very same year. This ‘mercenary book’ needed to be ‘stayed’, i.e. censored by the authorities, so that Sidney’s friends and relatives might take control, and also because publishing his works without consulting Greville or someone close to Sidney might damage his reputation or even his ‘religious honors’.

I rehearse this ancient tale because of its exemplary value for us today. From our point of view there seems nothing extraordinary about Greville’s actions: he is seeking to defend his friend’s literary estate from ‘mercenaries’ who steal intellectual property (IP): pirates. More…

Beyond words

15 December 2010 | This 'n' that

Meeting place of the Lahti International Writers' Reunion: Messilä Manor

‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must remain silent.’

This famous quotation from the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein has been adapted by the organisers of the Lahti International Writers’ Reunion (LIWRE): the theme of the 2011 Reunion, which takes place in June, will be ‘The writer beyond words’.

‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must write.’ How will the writer meet the limits of language and narration?

‘There are things that will not let themselves be named, things that language can not reach. Our senses give us information that is not tied to language – how can it be translated into writing? And how is the writer going to describe horrors beyond understanding or ecstasy that escapes words? How can one put into words hidden memories, dreams and fantasies that lie suppressed in one’s mind? Does the writer fill holes in reality or make holes in something we only think is reality?

‘Besides literature, there are other forms of interpreting the world; can the writer step into their realms to find new ways of saying things? The surrounding social sphere may put its own limits to writing. What kind of language can a writer use in a world of censorship and stolen words? How does the writer relate to taboos, those dimensions of sexuality, death or holiness that the surrounding world would not want to see described at all? Is it the duty of literature to go everywhere and reveal everything, or is the writer a guardian of silence who does not reveal but protects secrets and everything that lies beyond language?’

The first Writers’ Reunion took place in Lahti at Mukkula Manor in 1963; since then, more than a thousand writers, translators, critics and other book people, both Finnish and foreign, have come to Mukkula to discuss various topics.

In 2009 the theme was ‘In other words’, which inspired the participants to talk about the power of the written word in strictly controlled regimes, about fiction that retells human history and about the differences between the language of men and women, among other things. See our report from the 2009 Reunion; eleven presentations are available in English, too.

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) was a legend in his own lifetime, a media darling, a public drinker who had five children with four women. His oeuvre nevertheless encompasses 30 works, and his translations include Homer and James Joyce. The journalist Saska Saarikoski (born 1963) has finally read all that work – in search of the father whom he seldom met. The following samples are from his annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts over 30 years, Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012; see