Tag: writing

Human destinies

7 February 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

To what extent does a ‘historical novel’ have to lean on facts to become best-sellers? Two new novels from 2013 examined

When Helsingin Sanomat, Finland’s largest newspaper, asked its readers and critics in 2013 to list the ten best novels of the 2000s, the result was a surprisingly unanimous victory for the historical novel.

Both groups listed as their top choices – in the very same order – the following books: Sofi Oksanen: Puhdistus (English translation Purge; WSOY, 2008), Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is (Finnish translation Jää, ‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2012) and Kjell Westö: Där vi en gång gått (Finnish translation Missä kuljimme kerran; ‘Where we once walked‘, Söderströms, 2006).

What kind of historical novel wins over a large readership today, and conversely, why don’t all of the many well-received novels set in the past become bestsellers? More…

Kirjailijoiden Kalevala [The writer’s Kalevala]

7 February 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kirjailijoiden Kalevala

Kirjailijoiden Kalevala

[The writer’s Kalevala]

Toim. [Ed. by]: Antti Tuuri, Ulla Piela ja Seppo Knuuttila

(Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 92, the Kalevala Society’s yearbook 92)

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2013. 313 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-429-3

€47, hardback

The Kalevala is the Finnish national epic, compiled from oral folk poetry by Elias Lönnrot. It has provided a source of inspiration to Finnish culture since 1839. Kirjailijoiden Kalevala continues a project entitled ‘The artists’ Kalevala’, started in 2009. To start with, four scholars examine, from different viewpoints, the influence of folk poetry and the Kalevala on literature. Some twenty Finnish-language authors then approach the epic with original thoughts and literary means. The result may take the form of reminiscing, of a short story, poem or cartoon. In some texts the Kalevala is present only indirectly, in others some character of the epic is placed in the focus – Väinämöinen, Kullervo, Lemminkäinen or Aino. Kirjailijoiden Kalevala offers a multifaceted collection of viewpoints; aptly, the editors, in their foreword refer to the epic as a literary sampo, the mysterious, mythical object of the Kalevala that generates wealth and riches.

Decisions, decisions: the fate of virtual literature

28 November 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

Once upon a time: ‘Boyhood of Raleigh’ by J.E. Millais (1871). Wikipedia

In an era of ‘liveblogging’‚ we are all storytellers. But what’s the story, asks Teemu Manninen

One score of years ago, when the internet was new, the cultural critics of the time were fond saying that it would usher in a new utopia of free distribution of information: we would be able to read everything, know everything and share everything anywhere and every day.

Truly, they told us, we would become enriched by the internet to the point of not knowing what to do with all that wealth of knowledge, the amount of connections between us and the ever-increasing online availability of anyone with everyone, every waking hour.

Now that we really do have this always-on connectivity, you will indeed be available every waking hour: you will update your status, check your inbox, post pics and be available for chatting, texting, a quick email and a message or two, just to make sure no one is offended by your unreachability, since – from experience – a week’s worth of not tweeting or facebooking can make someone think that something serious has happened, or that you don’t even exist anymore. More…

Truth or hype: good books or bad reviews?

8 November 2013 | Letter from the Editors

‘The Bibliophile’s Desk’: L. Block (1848–1901). Wikipedia

More and more new Finnish fiction is seeing the light of day. Does quantity equal quality?

Fewer and fewer critical evaluations of those fiction books are published in the traditional print media. Is criticism needed any more?

At the Helsinki Book Fair in late October the latest issue of the weekly magazine Suomen Kuvalehti was removed from the stand of its publisher, Otavamedia, by the chief executive officer of Otava Publishing Company Ltd. Both belong to the same Otava Group.

The cover featured a drawing of a book in the form of a toilet roll, referring to an article entitled ‘The ailing novel’, by Riitta Kylänpää, in which new Finnish fiction and literary life were discussed, with a critical tone at places. CEO Pasi Vainio said he made the decision out of respect for the work of Finnish authors.

His action was consequently assessed by the author Elina Hirvonen who, in her column in the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, criticised the decision. ‘The attempt to conceal the article was incomprehensible. Authors are not children. The Finnish novel is not doing so badly that it collapses if somebody criticises it. Even a rambling reflection is better for literature than the same old articles about the same old writers’ personal lives.’ More…

Girls just want to have fun

3 October 2013 | Essays, Non-fiction, On writing and not writing

In this series, Finnish authors ponder the complexities of their profession. Susanne Ringell describes her work as sailing on sometimes stormy seas – without a skipper certificate, but with conviction

We are such stuff as dreams are made on; / and our little life is rounded with a sleep. (William Shakespeare, The Tempest.) In Swedish – my mother tongue and the language in which my pencil writes – the play is called Stormen, ‘The storm’. There are a lot of storms on the sea of dreams. The sky suddenly grows dark, and deceptive whirlwinds blow up, there are cold shivers and tornadoes, there is the Bermuda Triangle and the mighty chasm of the Mariana Trench. In its southern part is the world ‘s deepest marine environment, Challenger Deep, 11 kilometres. Our boats are small and fragile, and it ‘s a miracle they haven’t capsized more often.

It’s a miracle that in spite of it all we still so frequently reach our home harbour, that we arrive where we were bound for. Or somewhere else, but we do get there. We come ashore, we come ashore with what we set our minds on. More…

Cut time, paste space

12 September 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

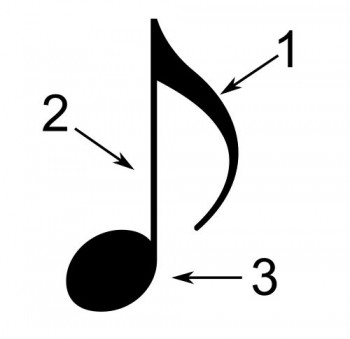

Back to basics. Parts of a musical note. Picture: Wikimedia

How different are the art of words and the art of sounds, author Teemu Manninen ponders, as he unexpectedly finds himself in the role of a musician in a performance. Time, space or both?

Some time ago I got the chance to participate in an unusual concert – as a performer: six players, myself included, were grouped around a table with a triangle in one hand and a glove in the other. Pieces of dry ice and a bucket of water were placed in front of each of us.

The performance began: we took a piece of dry ice and pressed it against the triangle. As the metal cooled, it burned through the ice, releasing gas, which in turn made the metal vibrate very fast. This produced a keening sound that filled the room. More…

No sex in Finland

31 July 2013 | Reviews

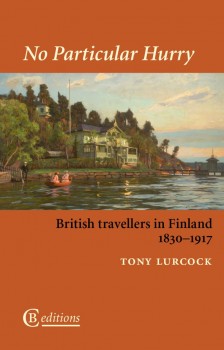

Tony Lurcock

Tony Lurcock

No Particular Hurry. British Travellers in Finland 1830–1917

London: CB editions, 2013. 278 p.

ISBN 978-0-9567359-9-7

£10, paperback

For British travellers of the late 18th- and early 19th-century Finland was mainly a transit area between Stockholm and St Petersburg, or on the way to exotic Lapland. A century later, the country was already a tourist destination in itself, a newly emergent nation state, though still subordinate to Russia.

Tony Lurcock’s anthology of travel literature about Finland is a sequel to his collection ‘Not so Barren or Uncultivated’: British Travellers in Finland 1760–1830 (reviewed in Books from Finland in June 2013).

The practical conditions of tourism were changing. English-language tour guides were being published, and Britain now had direct steamship connections to Finland, where rail, road and inland waterway traffic had been established. In 1887 the Finnish Tourist Association was founded with the aim of making life easier for foreign tourists on selected travel routes. However, the British – like many other foreigners – marvelled at some of the country’s curious features: the excruciating rural journeys by horse and cart, the wretched inns and strange choice of food, the rye bread and milk-drinking, and of course the sauna. But to this there were also exceptions, in the form of new, surprisingly resplendent hotels, world-class dinners and the life of the modern city. More…

Writes of passage

20 June 2013 | This 'n' that

Debating the word: participants at the Lahti Reunion. Photo: LIWRE

The 26th Lahti International Writers’ Reunion took place at Messilä Manor (some 120 km from Helsinki, on Lake Vesijärvi) from 15 to 18 June.

Chaired by Virpi Hämeen-Anttila and Joni Pyysalo, writers from more than 20 countries held discussions in Finnish, English and French.

This summer the theme was ‘Breaking walls’. ‘Problems demand answers, answers demand questions. If attitudes harden, arms talk, and everyone erects a wall around himself, where is literature in the equation? Is the highest wall right there inside the writer? Or is literature itself a protecting wall? What happens when walls break down?’

The first Writers’ Reunion took place in Lahti – first at Mukkula Manor – fifty years ago; more than a thousand writers, translators, critics and other professionals both Finnish and foreign have come to Lahti to discuss writing. The Reunion has always been open to the public as well.

The biannual Reunion began life in 1963, during the Cold War. Writers from both sides of the Iron Curtain met under the oaks of Mukkula. In the Reunion’s blog some participants and organisers share their experiences of the past; here, the meeting’s one-time international secretary Marianne Bargum recalls the late 1970s and early 1980s:

‘…following in the footsteps of the legendary publisher Erkki Reenpää who knew everybody and all languages, I did my best to persuade big stars to come to Mukkula. Some writers had difficulties when they realised that they were not as well known in Finland as in their own countries. The French poet Michel Deguy left after one day, very offended when nobody knew how big a name he was. (I met him in Paris some years later and he apologised.)

A scandal with huge political consequences came close when the French philosopher Bernard-Henry Lévy said some derogatory things about the Soviet head of state Brezhnev. The Russian delegate, Michael Baryshev, threatened to leave the conference, and Valentina Morozova, interpreter and politruk, had to phone the Soviet Embassy in Helsinki and explain that this was not very serious. The famous British critic and writer Al Alvarez did his best to calm down the antagonists in a panel.’

My own first personal experiences of this international fête (which could mean either wading in the mud on the way to the huge tent sheltering the discussions or basking in hot sunshine followed by the most gentle nightless nights), from the sunny summer of 1983: interviewing Salman Rushdie and Jayne Anne Phillips, among others, for the Finnish Broadcasting Company. Another time the bag containing some hundred copies of the latest issue of Books from Finland, fresh from the printing press, sat on a bus heading for Lahti while I sat on the one behind – which then broke down in the middle of the road, and this was before mobile phones. The driver did have a radio phone though, and the participants got their copies in time.

Soccer on the sand: Messilä beach. Photo: LIWRE

Among the traditions is a midnight football match between Finns and foreigners: the summer night is light and long. This time the result of the Finland against the rest of the world was convincing 6-3 to Finland.

Designbites

26 April 2013 | This 'n' that

Hey, design hipsters, wherever you are – after the super-serious focus brought about by Helsinki’s year as World Design Capital 2012, here’s a way to blow off steam.

Hey, design hipsters, wherever you are – after the super-serious focus brought about by Helsinki’s year as World Design Capital 2012, here’s a way to blow off steam.

Written by the comic-strip artist, illustrator and designer Kasper Strömman (born 1974), The Kasper Stromman Illustrated Design Encyclopedia (HuudaHuuda, 2013) consists of a series of post-ironic sound-bites on Finnish material culture.

Strömman was voted Graphic Designer of 2013 in Finland by Grafia (Association of Visual Communication Designers), by a jury that considered him to be a ‘catalyst, challenger and the standup comedian of graphic design’.

His book really is encyclopaedic, with entries ranging from the usual suspects (Artek, Arabia, Iittala) through the iconoclastic (in purist design terms, anyway: Angry Birds, the heteka sofa bed, Nokia gumboots and mobile phones) and the everyday (hapankorppu crispbread, vihreä kuula sweets, the Anttila mail-order catalogue and store) to the just plain wacky (the Aqua Tube disposable toilet roll, the Konrad ReijoWaara bridge, the Superlon mattress).

There are also fun sections on how to make your own design classics – for example, a pair of original orange Fiskars scissors (just use some paint) or Harri Koskinen’s glass block lamp – and outings to less-than-fashionable destinations (in eastern Helsinki) such as the Puhos shopping centre or the Itä-Pasila housing estate.

And so on. You can get a taste of what to expect at Kasper Strömman’s design blog in English (sadly discontinued, although it remains online. He’s started a new blog, although only in Finnish, entitled Kasper Diem…).

So far, so good; we like the idea, and it’s hard to think of another source that succeeds so well in bringing together every material thing we think of as Finnish. The problem is that it’s all delivered in faintly annoying one-liners – Kalevala Koru makes ‘jewellery based on bronze age findings, usually bought for you by your parents’; the Jugend style of architecture ‘should not be confused with “Hitler Jugend”’; Lapponia, Lapland in Latin, ‘useful to know if you were planning a ski trip in the Middle Ages’ – quite funny at first, but in the end they begin to get on your nerves. It’s like a diet of street food that never quite adds up to a meal.

The book’s foreword claims it to be ‘unique in the sense that it was put together with a minimum amount of research’ – no designers’ names or information-based facts. There’s an advantage here – it means that Strömman has felt free to include, among his opinions, plenty of oral and hearsay information, essential in dealing with everyday objects and their meanings.

But it also means that, too often, the author has let himself off the hook with a gag or a quip when staying with the subject would have been really rewarding. It’s a bit too much like material culture with attention deficit disorder. (It’s also hard to see who the book is really directed at – many of the jokes are so ‘in’ that it’s only those who are already in the know who will appreciate them.)

So hey, guys (Strömman refers to himself in the plural, so we will too), how about a challenge? Why not take yourselves seriously, and write the full-out version?

Fatherlands, mother tongues?

12 April 2013 | Letter from the Editors

Patron saint of translators: St Jerome (d. 420), translating the Bible into Latin. Pieter Coecke van Aelst, ca 1530. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikipedia

Finnish is spoken mostly in Finland, whereas English is spoken everywhere. A Finnish writer, however, doesn’t necessarily write in any of Finland’s three national languages (Finnish, Swedish and Sámi).

What is a Finnish book, then – and (something of particular interest to us here at the Books from Finland offices) is it the same thing as a book from Finland? Let’s take a look at a few examples of how languages – and fatherlands – fluctuate.

Hannu Rajaniemi has Finnish as his mother tongue, but has written two sci-fi novels in English, which were published in England. A Doctor in Physics specialising in string theory, Rajaniemi works at Edinburgh University and lives in Scotland. His books have been translated into Finnish; the second one, The Fractal Prince / Fraktaaliruhtinas (2012) was in March 2013 on fifth place on the list of the best-selling books in Finland. (Here, a sample from his first book, The Quantum Thief, 2011, Gollancz.)

Emmi Itäranta, a Finn who lives in Canterbury, England, published her first novel, Teemestarin tarina (‘The tea master’s book’, Teos, 2012), in Finland. She rewrote it in English and it will be published as Memory of Water in England, the United States and Australia (HarperCollins Voyager) in 2014. Translations into six other languages will follow. More…

Not a day without pen and paper

14 March 2013 | This 'n' that

For use and fun: stories for children by Z. Topelius

Zacharias Topelius wrote every day for almost 70 years. His published works contain almost 16,000 pages.

As he was also the editor of the Swedish-language newspaper Helsingfors Tidningar which he published twice a week for 20 years, his output, counted in pages, is enormous.

Author, journalist, historian, critic and pedagogue Topelius (1818–1898) wrote poetry, hymns, travelogues, serials, articles, short stories, fairy tales, textbooks and plays.

As for Finnish translations, his historical serial Fältskärns berättelser (‘The barber-surgeon’s tales’, 1853–1867) and Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’) are probably his most popular works.

In a bilingual (Swedish and Finnish), text-critical, annotated (and illustrated) project, entitled ‘Zacharias Topelius Skrifter’ (‘Z. T. writings’), Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland) will publish a large number of Topelius’s works in digital facsimile form. The selection grows continually.

Location, location, location

11 February 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

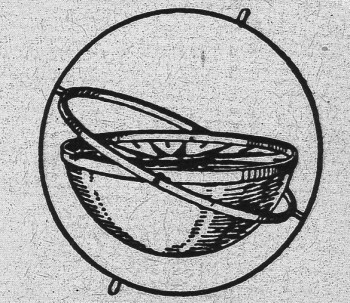

Before GPS: compass and and gimbal, 1570. Picture: Wikimedia

Art that requires navigation systems? Whatever next. In his column poet and writer Teemu Manninen wonders whether literature can function as ‘locative’. How to blend technology and art? Perhaps literature too might expand from the printed word

What if the Romantic poet John Keats had never published his poetry in print – if his works had been distributed only in manuscript form and read only by his friends and acquaintances? Had that been the case, the only way of hearing his poetry would have been at the salons and informal clubs that took place in literary people’s homes, at coffee houses, or other meeting places.

Keats might not even have, most likely, been in attendance himself, but maybe someone had a copy of a copy of a fragment of a poem that they might read to the gathered intellectuals and gentlefolk. You would have to have known the right people, have to have been at the right place at the right time to hear ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ read for the first and perhaps for the last time ever.

Or, what if Joyce had never intended for Ulysses to be published for the great reading public at all? What if, instead, he had left copies of each chapter around Dublin in the places where those chapters take place; what if, page by page, he had distributed his work in the actual locations of the events as they happened in his imagination? More…