Tag: war

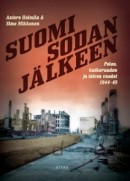

Antero Holmila & Simo Mikkonen: Suomi sodan jälkeen. Pelon, katkeruuden ja toivon vuodet 1944-1949. [Finland after the war, 1944-1949. Years of fear, bitterness and hope.]

16 June 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Antero Holmila – Simo Mikkonen

Antero Holmila – Simo Mikkonen

Suomi sodan jälkeen. Pelon, katkeruuden ja toivon vuodet 1944-1949. [Finland after the war, 1944-1949. Years of fear, bitterness and hope.]

Helsinki: Atena, 2015. 2650., ill.

ISBN 978-952-300-112-1

€34, hardback

Finland lost the Winter War and the Continuation War that followed, to the Soviet Union, and was then forced to engage in the short Lapland War to expel its former allies, the Germans. The return to peace was not easy, as the historians Antero Holmila and Simo Mikkonen demonstrate in this highly readable book. Loss of territory meant finding homes for more than 400,000 evacuees elsewhere in Finland, and this was not achieved without difficulty. Soldiers were demobilised and had to redomicile themselves in ordinary life and work; there was a shortage of housing; and heavy war reparations were to be paid to the Soviet Union. Leading politicians accused of appeasing the Soviet Union during the war received prison sentences, which many people considered wrong. The work highlights the aspirations of the Communists and the internal fighting on the political left. The Communist party, which had been banned, returned to the political stage and was successful in the 1945 elections. The majority of the nation was fearful of the growth of influence of the Communists and, through them, the Soviet Union. However, the Social Democrats, competing with the Communists for workers’ votes, succeeded in gaining considerably more votes than the Communists as early as 1948. Although strikes and conflicts occurred, conditions settled down gradually towards the end of the 1940s and the nation began to get back on its feet.

Images of war

5 May 2015 | This 'n' that

A soldier playing his accordion. Photo: SA-kuva

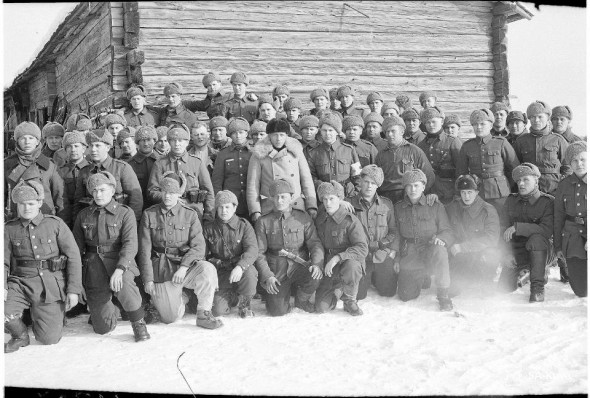

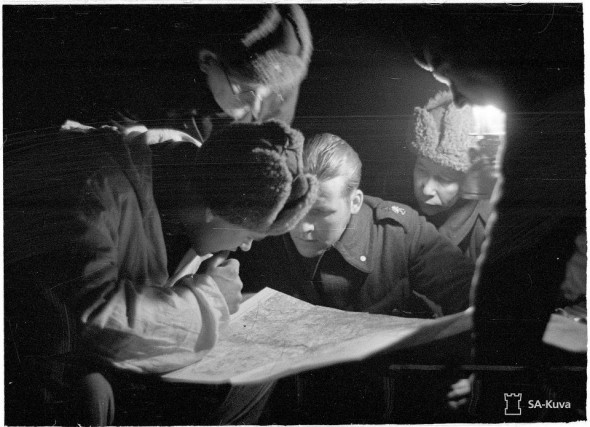

Between 1939 and 1944 Finland fought not one, but three separate wars – the Winter War (1939-45), the Continuation War (1941-44) and the Lapland War (1944-45).

We have become used to black-and-white images of the conflict, with their distancing effect. Among the 160,000 images in the Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive, however, are some 800 rare colour photographs from the Continuation War, which bring the realities of fighting much closer. The events pictured leap out of history and into the present. More…

The day peace came…

18 March 2015 | This 'n' that

Flags fly at half-mast in Helsinki. Photo: SA-Kuva

Seventy-five years ago, in the period known as the Phony War, while the rest of the world was preparing to fight, it looked as if hostilities were over for one country.

In the preamble to the Second World War, Soviet Union had attacked Finland on 30 November 1939, demanding substantial border territories for the protection of Leningrad. Germany had invaded Poland, and France and Great Britain had declared war; but the Nazi invasions of Norway and Denmark, Italy’s entry into the war, the Battle of Britain, Pearl Harbor, D-Day, Hiroshima, Nagasaki and all the other horrors of the Second World War were yet to come.

As the world watched, ‘plucky little Finland’, massively outnumbered in terms of both men and equipment but superior in morale, organisation and knowledge of the terrain, managed to keep the Red Army at bay for months – far longer than anyone had expected. Eventually, however, the Russians overcame Finnish border defences and the war ended on 13 March 1940. Now generally regarded by Finns as a defensive victory – Finland was not occupied by the Soviet Union – the peace treaty nevertheless imposed a heavy burden on Finland, which lost extensive territories in Karelia to the south and Salla to the north.

In the event, the war was far from over for Finland, which still had the Continuation War (1941-44) and the Lapland War (1944-45) to fight. But for the moment, the country was once more at peace.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the war, the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper has published a selection of photographs of the day peace came.

Soldiers of the 69th infantry regiment are able to eat in peace at last. Photo: SA-Kuva

A tree felled across a road provides a makeshift border point. Photo: SA-Kuva

Soldiers in their white winter camouflage rest in Viipuri after peace is declared. Photo: SA-Kuva

Soldiers in Kuhmo, north-eastern Finland, inspect the new border line. Photo: SA-Kuva

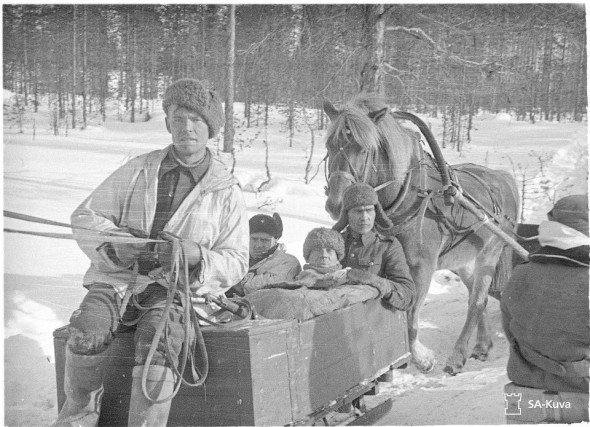

The last wounded soldiers are brought back by horse and cart from Saunajärvi. Photo: SA-Kuva

New from the archives

5 February 2015 | This 'n' that

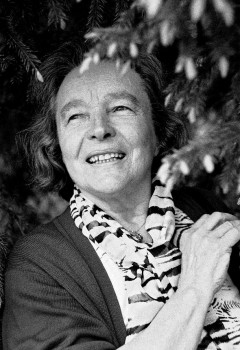

Eeva Kilpi. Kuva: Veikko Somerpuro

When we first published this piece, evacuation in Europe was a distant memory. The violent events that were to take place in what was then still Yugoslavia – Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia, Kosovo – were still to come.

Reading Kilpi’s description of her departure from eastern Karelia as an 11-year-old girl in 1939 with these more recent events in mind makes her evocation of the as-yet-unshattered familiarity of everyday life, the fragility of her prayers that everything will be all right, all the more poignant.

Kilpi (born 1927) is a poet, short-story writer and novelist who shot to international fame with her experimental, erotic novel Tamara (1972; English translation Tamara). She won the Runeberg Prize in 1990 for Talvisodan aika (‘The time of the winter war’), from which this extract is taken.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues apace, with a total of 355 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Ville Kivimäki: Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945 [Broken minds. The battle for the nerves of the Finnish soldiers 1939–1945]

28 November 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945

Murtuneet mielet. Taistelu suomalaissotilaiden hermoista 1939–1945

[Broken minds. The battle for the nerves of the Finnish soldiers 1939–1945]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 475 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-37466-5

€37, paperback

Ville Kivimäki bases this work on his dissertation. His research concentrates on how mentally wounded soldiers of the Winter War and the Continuation war (1939–1945), were treated and what sort of conclusions can be made as regards to their age and social background. Eighteen thousand men received, or were forced to undergo, psychiatric treatment; no doubt the number of those who remained untreated and those who suffered symptoms after the war was large. Cases increased not just during combat but also during the long periods of trench warfare. Mental problems were considered shameful, and often even the psychiatrists had moralising attitudes. Those who became ill were regarded as physically and mentally weaker material, trying to benefit from their illness. Treatment relied on German methods, mainly appropriate, even though unappropriate examples exist. The goal was to return the patient to the front, to useful work or home. Kivimäki also takes a look at those who did not fall sick and describes the community of the soldiers at the front and their ways of coping. Remains of wartime attitudes were, surprisingly, seen in doctor’s views as late as the 1990s, when remunerations were discussed. The book won the Finlandia Prize for Non-fiction in 2013.

Mothers and sons

Issue 1/2008 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Helvi Hämäläinen’s novel Raakileet (‘Unripe’, 1950. WSOY, 2007)

In front of the house grew a large old elm and a maple. The crown of the elm had been destroyed in the bombing and there was a large split in the trunk, revealing the grey, rotting wood. But every spring strong, verdant foliage sprouted from the thick trunk and branches; the tree lived its own powerful life. Its roots penetrated under the cement of the grey pavement and found rich soil; they wound their way under the pavement like strong, dark brown forearms. Cars rumbled over them, people walked, children played. On the cement of the pavement the brightly coloured litter of sweet papers, cigarette stubs and apple cores played; in the gutter or even in the street a pale rubber prophylactic might flourish, thrown from some window or dropped by some careless passer-by.

The sky arched blue over the six-and seven-storey buildings; in the evenings a glimmer could be seen at its edges, the reflection of the lights of the city. A group of large stone buildings, streets filled with vehicles, a small area filled with four hundred thousand people, an area in which they were born, died, owned something, earned their daily bread: the city – it lived, breathed….

Six springs had passed since the war…. Ilmari’s eyes gleamed yellow as a snake’s back, he took a dance step or two and bent over Kauko, pretending to stab him with a knife. More…

Wolf-eye

Issue 2/2004 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Käsky (‘Command’, WSOY, 2003). Introduction by Jarmo Papinniemi

Only once he had led the woman into the boat and sat down in the rowing seat did it occur to Aaro that it might have been advisable to tie the woman’s hands throughout the journey. He dismissed the thought, as it would have seemed ridiculous to ask the prisoner to climb back up on to the shore whilst he went off to find a rope.

It was a mistake.

After sitting up all night, being constantly on his guard was difficult. Sitting in silence did not help matters either, but they had very few things to talk about. More…

A life at the front

Issue 3/2001 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Marsipansoldaten (‘The marzipan soldier’, Söderström & Co., 2001). Introduction by Maria Antas

[Autumn 1939]

Göran goes off to the war as a volunteer and gives the Russians one on the jaw. Well, then. First there is training, of course.

Riihimäki town. Recruit Göran Kummel billeted with 145 others in Southern elementary school. 29 men in his dormitory. A good tiled stove, tolerably warm. Tea with bread and butter for breakfast, substantial lunch with potatoes and pork gravy or porridge and milk, soup with crispbread for dinner. After three days Göran still has more or less all his things in his possession. And it is nice to be able to strut up and down in the Civil Guard tunic and warm cloak and military boots while many others are still trudging about in the things they marched in wearing. The truly privileged ones are probably attired in military fur-lined overcoats and fur caps from home, but the majority go about in civilian shirts and jackets and trousers, the most unfortunate in the same blue fine-cut suits in which they arrived, trusting that they would soon be changing into uniform. More…

Looking back on a dark winter

Issue 4/1989 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the autobiographical novel Talvisodan aika (‘The time of the Winter War’), the childhood memoirs of Eeva Kilpi. During the winter of 1939–40 she was an 11-year old-schoolgirl in Karelia when it was ceded to the Soviet Union and the population evacuated

Time is the most valuable thing

we can give each other

War’s coming.

One day my father comes out with the familiar words in a totally unfamiliar way, while we’re sitting round the kitchen table eating, or just starting to eat.

He says to mother, as if we simply aren’t there, as if we don’t need to bother, or as if listening means not understanding. Or perhaps they’ve simply no other chance to speak to each other, as father’s always got to be off hunting, or on his way to the station, and mother’s always cooking. More…

The strike

Issue 4/1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Täällä Pohjantähden alla (‘Here beneath the North Star’), chapter 3, volume II. Introduction by Juhani Niemi

With banners held aloft, the procession of strikers moved towards the Manor. It was known that the strikebreakers had arrived early and that the district constable was with them. Just before reaching the field the marchers struck up a song, and they went on singing after they had halted at the edge of the field. The men at work in the field went on with their tasks, casting occasional furtive glances at the strikers. Nearest to the road stood the Baron and the constable. Uolevi Yllö’s head was bandaged: someone had attacked him with a bicycle chain as he left the field at dusk the evening before. Arvo Töyry was in the field too, the landowners having agreed that those who had got their own harrowing and sowing done should lend the others a hand. Not all the men in the field were known to the strikers. The son of the district doctor was there they noticed, and the sons of several of the village gentry, as well as the men from the smallholdings. More…