Tag: short story

Patsy, the artist of the lumber camps

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Atomintutkija ja muita juttuja (1950). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

Deep in the wilds, where the only sound is the sad, primeval sighing of the forest, it is easy to succumb to a mood of boredom and melancholy. It may sometimes occur to you that in such a place you are wasting your life. Real life goes on elsewhere, in places with more people, more signs of human activity, more light, more gaiety…

You fell a tree, severing a string of that mighty instrument, the forest. You saw it into logs, you strip off the bark: it all seems dull and pointless. Sometimes the rain decides to go on for days: the trees have streaming colds, droplets hang from every needle-tip. You make for the shelter of a lumber camp. But the low-roofed rest-hut, deep in the forest, looks a dreary place, the well-known faces are so dull, the talk so futile. You feel you know in advance what each man is going to say. And the food, too, is just the same as usual, the same old rubbishy mush. The sight of the pot, with its blackened sides, gives no pleasure: you know all too well what is in it. And those grubby playing-cards, how disgusting! The mere sight of them is enough to make you feel defiled… More…

The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Puhalluskukkapoika ja taivaankorjaaja (‘The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer’, 1983). Interview by Olavi Jama

Cold.

A chill west wind came over the blue ice. It went right to the skin through woollen clothes. Shivers ran up and down the spine, made shoulders shake.

In the bank of clouds close to the horizon, right where the icebreaker had crunched open a passage to the shore, hung a pale blotch, a substitute for the sun. It gave off more chill than warmth.

Lennu’s teeth were chattering.

He wore a buttoned-up windbreaker, a hand-me-down from Gunnar, over a heavy lambswool shirt. It couldn’t keep off the cold. More…

The report

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

And he left the road

Issue 2/1983 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three short stories from Maantieltä hän lähti (‘And he left the road’). Introduction by Eila Pennanen

And he left the road

And he left the road, walking straight ahead across fields and ditches, past barns and through bushes growing in the ditch. From the fields he went on to the forest, climbed a fence, walked past spruce and pine, juniper bushes and rocks, and came to the edge of a forest and to the swamp. He crossed the swamp, going through small groves of trees if they happened to be in his way. He went on walking rapidly across rivers, through forests, over seas and lakes, and through villages, and finally he came back to the very spot from which he had started walking straight ahead.

In the same way he walked at a right angle to the direction he had first taken and after that, a few times between those two directions. Every time he would start from the road and in the end would always come back to the road in the same direction as when he’d started off. On his rounds, after walking a bit, he would stop and look up every now and then, and each time he looked he would see the sky and sun or the moon and stars. More…

The Storm • September

Issue 3/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

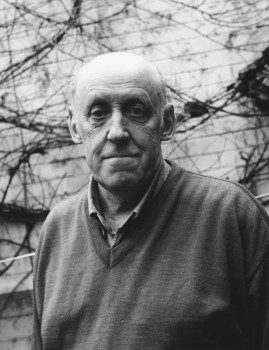

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Jag minns att jag drömde (‘I remember dreaming’, 1979)

The Storm

I remember dreaming about the great storm which one October evening over forty years ago shook our old schoolhouse by the park. My dream is filled with racing clouds and plaintive cries, of roaring echoes and strange meetings, a witch’s brew still bubbling and hissing in the memory of those great yellow clouds.

Our maths teacher – a small sinewy woman who seemed to have swallowed a question mark and was always wondering where the dot had gone, so she directed us in a low voice and with downcast eyes as if we didn’t exist – and yet her little black eyes saw everything that happened in the class, and weasel-like, were there if anyone disobeyed her – was writing the seven times table on the blackboard, when a peculiar light filled our classroom. We looked across at the window; the whole schoolhouse seemed to have been suddenly transformed into a railway station, shaking and trembling, a whistling sound penetrating the cold thick stone walls, and at raging speed, streaky clouds of smoke were sliding past the window, hurtling our classroom forward as if we were in an aeroplane. Our teacher stopped writing and raised her narrow dark head. Without a word, she went over to the window and stood looking out at the racing clouds. More…

Arska

Issue 3/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kaksin (‘Two together’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

A landlady is a landlady, and cannot be expected – particularly if she is a widow and by now a rather battered one – to possess an inexhaustible supply of human kindness. Thus when Irja’s landlady went to the little room behind the kitchen at nine o’clock on a warm September morning, and found her tenant still asleep under a mound of bedclothes, she uttered a groan of exasperation.

“What you do here this hour of day?” she asked, in a despairing tone. “You don’t going to work?”

Irja heaved and clawed at the blankets until at last her head emerged from under them.

“No,” she replied, after the landlady had repeated the question.

“You gone and left your job again?”

“Yep.” More…

Choosing a play

Issue 3/1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Leiri (‘The camp’). Introduction by Vesa Karonen

The local amateurs were having their theatre club meeting on a Friday evening in the main part of the parish hall. It was late August, the light was beginning to fade and no one had remembered to put the lights on. First the stage grew dark, then the floor, then the ceiling. The light lingered on the inside wall for the longest. There were creaks and groans from the rooms at the back and from the attic. The caretaker had been moving around in there about three in the afternoon, and his traces lingered, as they do in old buildings.

“Something of that sort but short, and it’s got to be bloody funny,” said the chairman, a carpenter called Ranta.

In the store cupboard there were 108 old scripts. Tammilehto, the secretary, hauled out about 30 scripts onto the table. His job was running a kiosk down the road.

“Nothing out of date,” said Ranta.

“There’s got to be a bit of love in it, I say,” said Mrs Ranta.

She had a taxi-driver’s cap on her head and was wearing a man’s grey summer jacket, a white shirt and a blue tie. Her car could be seen from the window. It was in the yard. She always parked her car so it could be seen from inside. More…

The Comb

Issue 3/1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Tilanteita (‘Situations’, 1962). Introduction by Vesa Karonen

The young man’s comb dropped behind the radiator under the window. The young man crouched down to look and felt with his fingers in between the pipes and along the floor. No trace of the comb.

Lose something on a train and it eludes you. A train ticket I left once – just placed it long enough on the window ledge for it, too, to fall behind the radiator. Couldn’t find it. The conductor came along, said “Any new fares! Tickets please.” I just sat still, totally unconcerned, until he’d gone. I’m sure there are little details which give the game away to conductors, they know who’s just got on.

New passengers are always somehow fresher, more alert. In winter, I hear, they look at the passengers’ feet. If there’s snow round the edges of the shoes, no need to hesitate. A lot of people are done for by looking straight in their eyes. Offenders always look straight back and then in the middle try to look somewhere else entirely. I was careful not to look steadily into the conductor’s eyes. It was easy when I concentrated on the way the long ventilator cords swung back and forth from the ceiling. They all swung in the same direction but some cords were a bit behind the others. Perhaps it was because the cords were all slightly different in weight and length. Now I remember – it’s not the weight that counts, just as it’s not weight that affects the way a pendulum swings. When the conductor had gone I began to look for my ticket again. I went on looking for it all the way to Tampere. The young man, too, would obviously go on looking for his comb until he got where he was going, without finding it. More…

The engineer’s story

Issue 2/1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Maailman kivisin paikka (‘The stoniest place in the world’, 1980). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Coffee was going to be served down by the river. The engineer took my elbow and led me across his paved courtyard and over his lawn; we settled ourselves down in cane chairs under the trees. Mirja came out of the house with a tray of coffee and coffee-cups, a loaf of sweet bread, already cut, some marble cake and some biscuits. The engineer said nothing. My eye wandered over the ample weeping birches by the river, the mist creeping up in the cool of the evening and shifting in the cross-pull of the breeze and the current, and I watched Mirja moving under the trees back to the house and then down again to the riverbank.

As we sipped our coffee we spoke about chance, and the part it plays in life, about my husband – for I was able to speak about him now: enough time had gone by. The engineer eased himself into a comfortable position, gave me a quick look and then launched off into an account of his own, about his trip abroad:

I spotted the news item as I was going through the morning paper on the plane. I sat more or less speechless all of the first leg, listening to Kirsti and her husband confabulating. I didn’t say anything during the stop-over in Copenhagen, either, where they wanted to get some schnapps and, of course, some chocolate ‘if Kirsti would really like some’. We came rushing back into the plane just as the last English, German and Danish announcements were coming over, and then we sat waiting for the take-off. That was delayed too because of a check-up (not announced), and then we were off again for Zurich, me without a word and they whispering together. Then it was the bus as far as the terminal, and after that a taxi to the hotel. Quite clearly Kirsti hadn’t heard a thing about it yet, and probably hadn’t had much contact with Erkki for quite some time, her new husband even less. More…

Locomotive

Issue 2/1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Dockskåpet (‘The doll’s house’). Introduction and translation by W. Glyn Jones

What I am about to write might perhaps seem exaggerated, but the most important element in what I have to tell is really my overriding desire for accuracy and attention to detail. In actual fact, I am not telling a story, I am writing an account. I am known for my accuracy and precision. And what I am trying to say is intended for myself: I want to get certain things into perspective.

It is hard to write; I don’t know where to begin. Perhaps a few facts first. Well, I am a specialist in technical drawings and have been employed by Finnish Railways all my life. I am a meticulous and able draughtsman; in addition to that I have for many years worked as a secretary; I shall return to this later. To a very great extent my story is concerned with locomotives; I am consciously using this slightly antiquated word locomotive instead of loco, for I have a penchant for beautiful and perhaps somewhat antediluvian words. Of course, I often draw detailed sketches of this particular kind of engine as part of my everyday work, and when I am so engaged I feel no more than a quiet pride in my work, but in the evenings when I have gone home to my flat I draw engines in motion and in particular the locomotive. It is a game, a hobby, which must not be associated with ambition. During recent years I have drawn and coloured a whole series of plates, and I think that I might be able to produce a book of them some time. But I am not ready yet, not by a long way. When I retire I shall devote all my time to the locomotive, or rather to the idea of the locomotive. At the moment I am forced to write, every day; I must be explicit. The pictures are not sufficient. More…