Tag: poetry

Landscapes of the mind

Issue 2/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

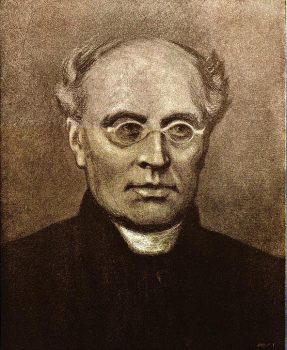

Tuomas Anhava. Photo: Otava

In his book Suomalaisia nykykirjailijoita (‘Contemporary Finnish writers’), Pekka Tarkka describes Tuomas Anhava’s development as a poet as follows: In his first work, Anhava appears as an elegist of death and loneliness; and this classical temperament remains characteristic in his later work. Anhava is a poet of the seasons and the hours of the day, of the ages of man; and his scope is widened by the influence of Japanese and Chinese poetry. As well as his miniature, crystalclear, imagist nature poems, Anhava writes, in his Runoja 1961 (‘Poems 1961’), brilliant didactic poems stressing the power of perception and rebuffing conceptual explanation. The mood in Kuudes kirja (‘The sixth book’, 1966) is of confessionary resignation and intimate subjectivity.

Anhava’s literary inclinations reflect his most important translations, which include William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1959), selections of Japanese tanka poetry (1960, 1970, 1975), Saint John Perse’s Anabasis (1960), a selection from the works of Ezra Pound, published under the title Personae, and selections from the work of the Finland-Swedish poets Gunnar Björling and Bo Carpelan.

![]()

Song of the black

My days must be black,

to make what I write stand out

on the bleached sheets of life,

my rage must be the colour of death, to make my black love stand out,

my nights must be summer white and snow white,

to make my black grief burn far,

since you're grieving and I love you

for your undying grief.

Let the sun's rolled gold gild dunghills,

let the moon's blue milk leak out till it's empty,

we're not short of those.

The obscure black darkness of the cosmic night

glitters on us enough.

From Runoja (1955)

Poems

Issue 4/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

Birds of passage

Ye fleet little guests of a foreign domain,

When seek ye the land of your fathers again?

When hid in your valley

The windflowers waken,

And water flows freely

The alders to quicken,

Then soaring and tossing

They wing their way through;

None shows them the crossing

Through measureless blue,

Yet find it they do.

Unerring they find it: the Northland renewed,

Where springtime awaits them with shelter and food,

Where freshet-melt quenches

The thirst of their flying,

And pines’ rocking branches

Of pleasures are sighing,

Where dreaming is fitting

While night is like day,

And love means forgetting

At song and at play

That long was the way. More…

Poems

Issue 3/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by Pertti Lassila

If you come to the land of winds, to the bottom of the sea,

there are few trees, plenty of icy wind

from shore to shore.

You can see far

and see nothing.

Around you screech the newborn plains

still wet from fog

but clear as a dream

at the edge, the sea

beneath, the deep earth

above, the wide expanse

shouts to you and to the plains

about being

it looks at you and asks

When we returned home

and leaned against the long table

we could see the simple grain of the wood

and our weariness turned into knowledge

of why we had had to go away:

to come back to see the uncharted patterns

in the table at home.

From Lakeus (‘The plain’, 1961)

Poems

Issue 2/1985 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Introduction by Bo Carpelan

A flower beckons there, a secent beckons there, enticing my eye. A hope glimmers there. I will climb to the rock of the sky, I will sink in the wave: a wave-trough. I am singing tone, and the day smiles in riddles.

*

Like a sluice of the hurtling rivers I race in the sun: to capture my heart; to seize hold of that light in an inkling: sun, iridescence. In day and intoxication I wander. I am in that strength: the white, the white that smiles.

*

To my air you have come: a trembling, a vision! I know neither you nor your name. All is what it was. But you draw near: a daybreak, a soaring circle, your name.

Eroica

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Ilpo Tiihonen. Photo: Irmeli Jung

Poems from From Eroikka (‘Eroica’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Ilpo Tiihonen (born 1950) published his first collection of poetry in 1975. From the beginning, his poems have been couched in the language of the street, and he uses slang liberally. Tiihonen has always been opposed to the miniature idylls of nature that were so characteristic of the 1970s. He aims at the secularisation of poetry, and he uses humour and comedy as a counterweight to high culture. He has evidently been influenced in his technique by Mayakovsky and Yesenin, to whom he often refers in his poems. His preferences in the poetic tradition are apparent in the fresh and liberal new interpretations of poems by Gustav Fröding contained in his collection Eroikka. Unusually for a contemporary Finnish poet, Tiihonen makes extensive use of rhyme. The result is often strongly lyrical poems that could almost be called modern broadsheet ballads, and may also bring Brecht to mind. More…

Bearded Madonna

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Parrakas madonna (‘Bearded Madonna’, 1983). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

The first volume of poems by Eira Stenberg (born 1943) appeared in 1966; since then she has published both poems and children’s stories. In her most recent collection, she examines human relationships within the family, divorce, motherhood and childhood. Stenberg’s voice is clear and concrete. Her treatment of both mother and child is unsentimental, sometimes ironic; perceptively and farsightedly she deals with the importance of childhood in the way it predestines the fate of the individual. No love or hate burns/ like that we receive as a gift from childhood, Stenberg writes in one of her poems. The home – protective, restrictive and punishing – is often the scene of her poems. The man, the father, is the butt of considerable irony and criticism, but Stenberg also destroys the myth of the madonna-like mother and the idyll of the home. More…

An intimation of Paradise

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Paratiisiaavistus (‘An intimation of Paradise’, 1983). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Satu Salminiitty (born 1959) has published only one collection of poetry since her first appeared in 1981, but with these two volumes she has achieved considerable success. She writes with a fine rhetoric using language and rhythm that are far removed from those of spoken Finnish. Religious pathos has a prominent place in her work, and her poems often derive from praise, prayer or even magic incantations; Salminiitty is a creator of vision who trusts to her metaphysical intuition, a quality not generally discernible among today’s Finnish poets. Equally rare is her lively faith in the goodness and beauty of people and of the world. A conscious rejoinder to materialism, pessimism and fear of the future can be read in her poems. More…

Narcissus in winter

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

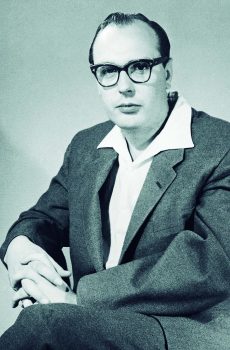

Risto Ahti. Kuva: Harri Hinkka

Poems from Narkissos talvella (‘Narcissus in winter’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Risto Ahti (born 1943) published his first work in 1975. His poetic expression finds form remarkably often in prose poems, and Narkissos talvella is made up exclusively of these. His poems transmute language into a mystical, surreal world, sometimes enigmatic and subjective in the extreme, and at its best strangely suggestive. It is as if Ahti’s world were in a state of constant change, subjected to a relentless process of demolition and rebuilding. The experience of the individual, generally his encounter with truth, is central to many of Ahti’s poems; the inner reality of a person manifests itself as more essential than the outward appearance. Ahti’s poems exhibit a fruitful contradiction: on the one hand, the accuracy with which he uses words and, on the other, the continual shape-changing and lack of definite boundaries of the world they describe. More…

Poems

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Interview by Philip Binham

Birdmount

I hear a happy tale, it makes me sad:

no-one will remember me for long.

I will send a letter with nothing inside, the emptiness will reek

as the pines do, of fruit-peel and of smoke,

a scent only.

Here I have stayed a week, seven riverside days.

The river treads the mill, ah, treads the mill,

the river’s wide, this is a placid reach, the sky is near:

smoke, like the shadow of a birdflock passing, nothing else.

And now it is September:

there are more pine trees here, and more darkness too. More…

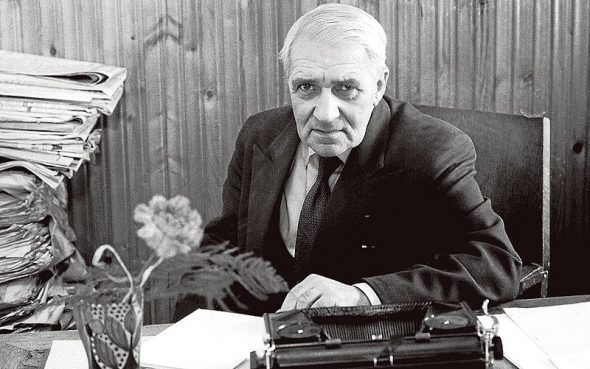

The power game

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

The starving, too

Issue 2/1983 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Poems from Det som alltid är (‘What always is’). Introduction by Sven Willner

The starving, too

The starving, too, can

love, but their love is

simplified to hunger, its

principle. With the help of

another’s love the sated love

themselves, which they

otherwise would hate. And

stronger is perhaps the love

that saves,

but deeper is the one that

seals. People, of

whom all that is left is

a heart and its

two arms, give one another

their hunger. More…