Tag: novel

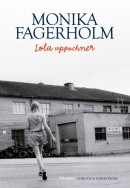

Monika Fagerholm: Lolauppochner [Lola upside down]

20 September 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Lolauppochner

Lolauppochner

[Lola upside down]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 461 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2997-7

€ 31, hardback

Lola ylösalaisin

Suomentanut [Translated into Finnish by]: Liisa Ryömä

Helsinki: Teos, 2012. 300 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-480-3

€28.40, hardback

Lolauppochner (‘Lola upside down’) is a more authentic crime novel than the same author’s Den amerikanska flickan (English translation: The American Girl, 2004) and Glitterscenen (The Glitter Scene, 2009), though they too wove their dense fiction around an old crime. Readers who are at ease in Fagerholm’s luxuriant wordscapes with their tragic teens, country bumpkins and summer visitors will still be able to find their way around the small community where Jana Marton, a teenage girl on the way to her job at the local store, discovers the corpse of a boy, a key player among the local gilded youth. The novel’s opening, and many sections that follow, are extremely effective, with sharp and lightning-swift characterisations and a fine intuition for both the fear and the excitement in the social circle where the murder turns up hidden connections like worms from the soil. But the novel is too long for its own good – somewhere towards the end it ceases to gain depth, and the gallery of characters starts to feel too big. All the same, this book is a must for Fagerholm’s readership at home and abroad. A bonus for locals – and attentive outsiders – is present in the outlines of the small seaside town of Ekenäs that can be glimpsed behind the text. They supply a kind of physical magic that rubs off on much else besides – characters, moods and sense of place.

Translated by David McDuff

Olli Jalonen: Karatolla

14 September 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Karatolla

Karatolla

Helsinki, Otava, 2012. 238 p.

ISBN 978-951-1-26469-9

€34.10, hardback

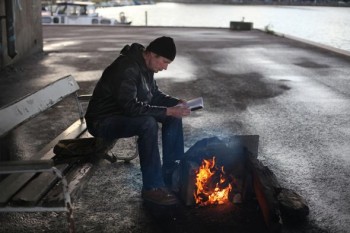

Karatolla is a Finnish dialect word for a bonfire that is lit at New Year or Easter. One of the main characters in Olli Jalonen’s new novel (his twenty-first publication to date) is an artist called Valo, ‘Light’. By the fires of his youth he has come to learn that the world is composed of nine basic elements: fire, smoke, light, earth, water, snow, ice, air, and time. At the beginning of the twenty-first century Valo and his colleague the architect Silla set out to construct a major European art work in which pyramids built of the above-mentioned elements are assembled in Prague, Brussels, Santiago de Compostela, Krakow, Reykjavik, Bergen, Helsinki, Avignon and Bologna respectively. In this novel Jalonen (born 1954) develops themes from his previous novel Yhdeksän pyramidia (‘Nine pyramids’), published in 2000: the events have moved forward ten years. When the project is completed, a nascent love affair between Light and Silla ends when Light falls victim to a fatal illness. Jalonen’s narrative is fascinating; the construction of pyramids, the cities in which they are constructed and the characters are portrayed with great skill, developing themes of artistry, honesty and the fragility of love. Much open space is left for the reader’s thoughts and imagination.

Translated by David McDuff

Money makes the world go round

31 August 2012 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Mr. Smith (WSOY, 2012). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

I have a confession to make.

I couldn’t have lived on my salary. Most people would solve this by taking out a loan, living on credit. I’ve never lived in debt. Instead I’ve had to make my modest capital grow by investing it – through the company, of course, because irrespective of their colour governments generally understand companies better than small investors. You have to make money somewhere other than the Social Security Office.

Work doesn’t make money; money makes money.

You have to let money do the work.

This is nothing short of a profound human tragedy: most people are forced to waste the majority of their lives, to use it in the service of complete strangers, for unknown purposes, doing something for money that they would never do if they didn’t have to. The most shocking thing is that people actively seek out this state of affairs, strive towards it; it is a goal towards which society lends us its full support, no less.

Such wage slavery is called ‘work’. More…

Temporarily out of order

Extracts from the novel Hullu (‘The lunatic’, Teos, 2012). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

I found myself standing in front of the noticeboard. The rules were on a sheet of paper:

Ward 15 5-C

MEAL TIMES:

Breakfast 8:00 AM

Lunch 11:45 AM

Dinner 4:30 PM

Evening Snack 7:30 PM

COFFEE:

After lunch

We recommend leaving money, valuables, and bankbooks for storage in the ward valuables locker. We take no responsibility for items not left in the locker! Money may be retrieved 1–3 times per day. Use of mobile phones on the ward by arrangement.

VISITING HOURS:

M–F 2–7 PM

Sa–Su 12–7 PM

PERSONAL CLOTHING:

Use of one’s own clothing by individual arrangement. Clothing care individual. Washer and dryer available for use in the evenings after 6 PM.

OUTDOOR RECREATION:

Arranged individually according to health condition. Outdoor pass does not include the right to leave the area.

VACATIONS:

Vacations arranged during morning report, according to health condition.

NOTA BENE!

Smoking is only allowed on the smoking balcony! Smoking prohibited from 11 PM to 6 AM.

Pastor Karvonen available by appointment.

These were impossibly difficult rules. I read them through three times and simply did not understand. ‘Clothing care individual.’ ‘Outdoor pass does not include the right to leave the area.’

What did these sentences mean? With whom did you schedule the pastor and how? And why? More…

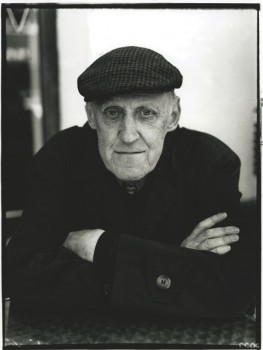

Tuomas Kyrö: Mielensäpahoittaja ja ruskeakastike [Taking offence: brown sauce]

25 April 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Mielensäpahoittaja ja ruskeakastike

Mielensäpahoittaja ja ruskeakastike

[Taking offence: brown sauce]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2012. 130 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-39079-5

€23.90, hardback

The most popular book by Tuomas Kyrö (born 1974), so far, has been his sixth novel, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Taking offence’: literally ‘He who takes offence’, 2010). It has sold nearly 65,000 copies as a book and audiobook. The protagonist is a 80-something man, a sturdy old bear who lives in the countryside, now alone, because his demented wife has been taken into care and the children have long since left home. Kyrö inserts genuine humour into the monologues of his stubborn – but by no means simple – character, defiantly critical, opposing new gadgets, fads and all sorts of silly stuff of the contemporary society. In this sequel Kyrö still manages to entertain the reader with his detailed portrait: now Mr Grumpy has to learn to cook, because the food a paid helper brings in just isn’t good enough. With the potato as the cornerstone of his diet, he finally learns how to make good, fatty and salty meals of meat and veg. ‘One must remember what’s important in life, marriage and prostate problems. Time and patience.’ Illustrations remind the reader of the old times: photographs of television programmes and printed recipes from the 1960s and 1970s.

Success after success

9 March 2012 | This 'n' that

The women of Purge: Elena Leeve and Tea Ista in Sofi Oksanen's Puhdistus at the Finnish National Theatre, directed by Mika Myllyaho. Photo: Leena Klemelä, 2007

Sofi Oksanen’s Purge, an unparalleled Finnish literary sensation, is running in a production by Arcola Theatre in London, from 22 February to 24 March.

First premiered at the Finnish National Theatre in Helsinki in 2007, Puhdistus, to give it its Finnish title, was subsequently reworked by Oksanen (born 1977) into a novel – her third.

Puhdistus retells the story of her play about two Estonian women, moving through the past in flashbacks between 1939 and 1992. Aliide has experienced the horrors of the Stalin era and the deportation of Estonians to Siberia, but has to cope with the guilt of opportunism and even manslaughter. One night in 1992 she finds a young woman in the courtyard of her house; Zara has just escaped from the claws of members of the Russian mafia who held her as a sex slave. (Maya Jaggi reviewed the novel in London’s Guardian newspaper.) More…

Wo/men at war

9 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

In reviews of Finnish books published this past autumn, young women writers’ portraits of war were pigeonholed time and again as a ‘category’ of their own. This gendered observation has been a source of annoyance to the writers themselves.

Jenni Linturi, for instance, refused to ruminate on the impact of her sex on her debut novel Isänmaan tähden (‘For the fatherland’, Teos), which describes the war through the Waffen-SS Finnish volunteer units and the men who joined them [1,200 Finnish soldiers were recruited in 1941, and they formed a battalion, Finnische Freiwilligen Battaillon der Waffen-SS].

The work received a well-deserved Finlandia Prize nomination. Tiring of questions from the press about ‘young women and war’, Linturi (born 1979) was moved to speculate that some critics’ praise had been misapplied due to her sex. The situation is an apt reflection of the waves of modern feminism and the reasoning of the so-called third generation of feminists, who reject gender-limited points of view on principle. More…

Johanna Sinisalo: Enkelten verta [Angels’ blood]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Enkelten verta

Enkelten verta

[Angels’ blood]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 274 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-414-8

€ 32, hardback

The literary career of Johanna Sinisalo (born 1958) has embraced fiction, drama, sci-fi and children’s books. Her 2000 Finlandia Fiction Prize-winning fantasy novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi and the novel Linnunaivot (2008) have been published in English as Not before Sundown and Birdbrain respectively. In this new novel, set in the near future, the central role is played by bees: widespread beehive failures in the United States and the resulting drop in pollination have resulted in an enormous food shortage that threatens the world economy. Orvo is a loner, the father of Eero, his grown-up son. Sinisalo cleverly works in animal rights activist Eero’s controversial blog comments on animal rights and modern man’s flawed relation to nature. However, this is also the novel’s biggest problem, as the blogging starts to weaken the story, of three generations of men in a family. Both the mythic, parallel reality of the bees and the tough-and-tender relationship between father and son are strong indications of Sinisalo’s narrative skill.

Translated by David McDuff

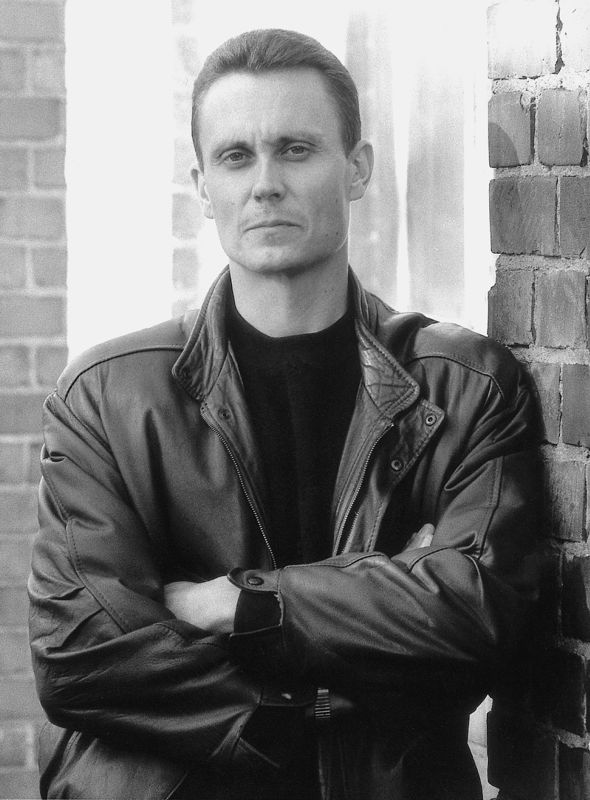

Asko Sahlberg: Häväistyt [Disgraced]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Häväistyt

Häväistyt

[Disgraced]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 331 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-38275-2

€ 33, hardback

The tenth novel by Asko Sahlberg (born 1964) is reminiscent of the earlier works of this distinctive author: its principal characters are hardened by experience and lead their lives somewhere in the Finnish countryside during a recent period of the country’s history. The sentences are beautifully constructed, and the pace of the narrative is very slow – sometimes even too slow. The main role is played by a middle-aged man who is running away with a woman and a small boy. What they are running away from for a long time remains a puzzle, as does the question of who they are looking for, a man called The Master. In the flashbacks of the last part of the book all is explained, and the rhythm of the story quickens. Considering the book’s desolate, even fatalistic view of the world, it is slightly surprising that everything eventually turns out as happily as in a fairytale. But perhaps this is Sahlberg’s tribute to his characters, and to all of us human beings, for whom he seems to care a great deal? His novel He (2010) will be published in February in England under the title The Brothers (Peirene Press).

Translated by David McDuff

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen: Kallorumpu [Skull drum]

23 December 2011 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kallorumpu

Kallorumpu

[Skull drum]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 390 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-413-1

€ 27.40, hardback

Eeva-Kaarina Aronen (born 1948) did not begin her writing career untill 2005, after a long career as editor of the newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. Her third novel Kallorumpu was shortlisted for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011. Aronen’s interest in historical characters and themes that challenge historical truth was already evident in the of her first novel Maria Renforsin totuus (‘The truth of Maria Renfors’, Teos, 2005). At the centre of Kallorumpu is the legendary figure of Finland’s Field Marshal C.G. Mannerheim (1867–1951). The book concentrates on the description of one day in November 1935 by an old filmmaker, the narrator of the novel, who is showing his documentary to a small group of viewers in the present day. He comments on his own film, complementing it with stories about Mannerheim’s home in Helsinki. At home the Marshal’s staff – a cook, a maid and a valet – not only provide narrative twists and turns, but also an insight into the class divisions of the Finnish civil war. Aronen’s portrayal of her gallery of characters is an interesting one, and the novel’s demanding structure, with its alternating time zones, is sound.

Translated by David McDuff

Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011

1 December 2011 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2011, worth €30,000, is Rosa Liksom, for her novel Hytti no 6 (‘Compartment number 6’, WSOY): read translated extracts and an introduction of the author here on this page.

The prize was awarded on 1 December. The winner was selected by the theatre manager Pekka Milonoff from a shortlist of six.

‘Hytti nro 6 is an extraordinarily compact, poetic and multilayered description of a train journey through Russia. The main character, a girl, leaves Moscow for Siberia, sharing a compartment with a vodka-swilling murderer who tells hair-raising stories about his own life and about the ways of his country. – Liksom is a master of controlled exaggeration. With a couple of carefully chosen brushstrokes, a mini-story, she is able to conjure up an entire human destiny,’ Milonoff commented.

Author and artist Rosa Liksom (alias Anni Ylävaara, born 1958), has since 1985 written novels, short stories, children’s book, comics and plays. Her books have been translated into 16 languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (journalist and critic Hannu Marttila, journalist Tuula Ketonen and translator Kristiina Rikman) shortlisted the following novels: Kallorumpu (‘Skull drum’, Teos) by Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, William N. Päiväkirja (‘William N. Diary’, Otava) by Kristina Carlson, Huorasatu (‘Whore tale’, Into) by Laura Gustafsson, Minä, Katariina (‘I, Catherine’, Otava) by Laila Hirvisaari, and Isänmaan tähden (‘For fatherland’s sake’, first novel; Teos) by Jenni Linturi.

Rosa Liksom travelled a great deal in the Soviet Union in the 1980s. She said she hopes that literature, too, could play a role in promoting co-operation between people, cultures and nations: ‘For the time being there is no chance of some of us being able to live on a different planet.’

Autumn’s child

17 November 2011 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Bo Carpelan’s novel Blad ur höstens arkiv. Tomas Skarfelts anteckningar (‘Leaves from autumn’s archive. The notes of Tomas Skarfelt’). Introduction by Clas Zilliacus

When I took my first walk here in Udda, along the road down to the end of the bay, my legs wanted to go left up to the forest, while I strove to walk straight ahead. It was an unsteadiness reminiscent of being slightly drunk. A slight vertigo I have already noticed before. Trees soughed through me and the water of the bay tasted almost like salt on my lips. All sorts of things try to pass straight through me nowadays. I am becoming a general store. The few people I know go there and choose, and I try to sell. Most of it is old memories with attendant dust. They are in no chronological order at all, and make involuntary, rapid leaps, like kangaroos. Even when I went to school they hopped around. They forced me to learn my lessons by heart. They continued to skip over me at university and added an extra complexity to my studies in general history: concentrate of reign lengths.

And if I followed my legs and gave not a damn about my dead straight road? Digressions from what was planned provided me later on with my best experiences, and coincidences were grains of gold. Improvisations were lucky throws, or disasters. Afterwards came the restrictions, the constructions, the architecture. Now only that squared-paper notebook remains with its pitfalls. The uncertainty is sometimes imperceptible, but is there: Am I not superfluous? Are not my legs somewhat irrational? More…