Tag: novel

The three-minute redemption

28 March 2013 | Fiction, Prose

Artist and writer Hannu Väisänen’s alter ego, Antero – who has appeared in Väisänen’s earlier autobiographical novels – is a young artist in his new novel Taivaanvartijat (‘The guardians of heaven’, Otava, 2013). Antero is invited to create the altarpiece for a new church. He rejects conventional, ecclesiastical ‘Sunday art’ and uses simple and versatile everyday symbols; his design contains an ordinary Finnish door key, familiar to everybody. The clergymen and laywomen are appalled: is this art, is it appropriate? In this extract the frustrated Antero takes a therapeutic break – on a roller-coaster

Now I need to get another beat into my head. What can help me forget those morose, curled up creatures, their strange commands and scents? I remember the roller-coaster. And I remember the ancient lore that it’s good to ride the roller-coaster with a lover before you attempt anything else. I go home quickly, throw down my sketch-book and my unnecessarily businesslike briefcase, exchange my suit, which was supposed to indicate devotion, for a windcheater, arrange my hair more carelessly, get on my bike and cycle to the funfair where I know the roller-coaster, the genuine, real, old-fashioned, clanking roller-coaster, to be.

Who could have been the first person to imagine the delights of the roller-coaster? Into whose happy capacity for daydreaming did it fall? Who saw those massive iron tentacles in their figure-eight shapes, those stretched and knotted rings of eternal joy? Who understood that on such a ride shame and anxiety would fall out of one’s pockets? It’s claimed that the first roller-coaster was invented by Catherine the Great. The monarch, with her multifarious patronage of culture, commissioned in Oranienbaum, St Petersburg, the first Montagne Russe amid the amusements of the wise: a Russian mountain with its ice-paths, raised into the air, which melted with the coming of spring. Who else could understand this organ-stirring amusement as deeply as the Great Wife with her hundreds of lovers. In the grip of mortal fear, I too always pray: before I am laid in earth, before the crematorium’s oven, take me once more to the roller-coaster. More…

Johanna Holmström: Asfältsänglar [Asphalt angels]

21 March 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Asfältsänglar

Asfältsänglar

[Asphalt angels]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 294p.

ISBN 978-951-52-3120-8

€29.90, hardback

Finnish translation:

Itämaa

Helsinki: Otava, 2012. 333 p.

Suom. [Translated by] Tuula Kojo

ISBN 978-951-1-26841-3

€29.90, hardback

The immigrant novel has not played a significant role in contemporary Finnish literature; since the wave of Russian refugees in the early 19th century, there have been few immigrants to Finland. In her short story collection Camera Obscura (2009) Johanna Holmström (born 1981) managed to combine realism and fantasy in a fascinating way; her new novel, Asfaltsänglar, is the directly yet eloquently told story of two young immigrant sisters. Leila, bullied at school, is becoming a drop-out, while Samira, who has tried to live according to western norms, lies unconscious after an unexplained accident. Their Finnish mother is a fanatical convert to Islam and their father comes from the Maghreb region. The novel confronts claustrophobic Arabic family culture and western ideals of freedom, taken so far that people completely lose any sense of responsibility for one another, with the adults’ betrayal of their children playing a key role. Holmström goes to great lengths to give a balanced portrayal of both cultures and show why her characters act as they do, even when the results are tragic.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Me and my shadow

Hotel Sapiens is a place where people are made to take refuge from the world that no longer is habitable to them; the world economy has fallen – like the House of Usher, in Edgar Allan Poe’s story – and with it, most of what is called a civilised society. A rapid synthetic evolution has taken humankind by surprise, and the world is now governed by inhuman entities called the Guardians. ‘Kuin astuisitte aurinkoon’ (‘As if stepping into the sun’) is a chapter from the novel Hotel Sapiens ja muita irrationaalisia kertomuksia (‘Hotel Sapiens and other irrational tales’, Teos, 2012), where several narrators tell their stories

The fog banks have dissipated; the sky is empty. I cannot see the sails or swells in its heights, nor the golden cathedrals or teetering towers. I would not have believed I could miss a fog bank, but that’s exactly what it’s like: its disappearance is making me uneasy. For all its flimsiness and perforations it was our protection, our shield against the sun’s fire and the stars’ stings. Now the relentlessly blazing sun has awakened colours and extracted shadows from their hiding places. The moist warmth has dried into heat and the Flower Seller’s herb spirals have dried up into skeletons. The leaves on the trees are full of bronze, sickly red and black spots. Though there is no wind and autumn is not yet here, they come loose as if of their own volition, as if they wanted to die.

This morning, as I was strolling up and down the park path as usual, I saw another shadow alongside my own.

– Ah, you’re back! I said. – I wondered what had happened to you after you lost your shadow; how did you manage to change into your own shadow yourself? More…

Happy days, sad days

28 February 2013 | Reviews

Pekka Tarkka

Pekka Tarkka

Joel Lehtonen II. Vuodet 1918–1934

[Joel Lehtonen II. The years 1918–1934]

Helsinki: Otava, 2012. 591 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-25924-4

€38.50, hardback

A well-meaning bookseller’s idealism, inspired by Tolstoyan ideology, is brought crashing down by the laziness and ingratitude of the man hired to look after his estate: conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the ‘ordinary folk’ are played out in heart of the Finnish lakeside summer idyll in Savo province.

Taking place within a single day, the novel Putkinotko (an invented, onomatopoetic place name: ‘Hogweed Hollow’) is one of the most important classics of Finnish literature. Putkinotko was also the title of a series (1917–1920) of three prose works – two novels and a collection of short stories – sharing many of the same characters [here, a translation of ‘A happy day’ from Kuolleet omenapuut, ‘Dead apple trees’, 1918] .

In 1905 Joel Lehtonen bought a farmstead in Savo which he named Putkinotko: it became the place of inspiration for his writing. With an output that is both extensive and somewhat uneven, the reputation of Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) rests largely on the merits of his Putkinotko, written between 1917 and 1920. More…

Riku Korhonen: Nuku lähelläni [Sleep close to me]

28 February 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Nuku lähelläni

Nuku lähelläni

[Sleep close to me]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2012. 300 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-39305-5

€29.90, hardback

Contrary to the more agreeable expectations that might be prompted by its title, this book is dominated by the image of a masked anarchist raising his hand in a cloud of teargas. Korhonen (born 1972) is an analyst of social problems who in his most recent novels has expanded his field of vision from the realities of suburban Finland to the global centres of money and power. This novel, his fifth book, offers a pessimistic picture of Europe today. The collapse of the economy has left people with an inner sense of emptiness and anger. A young man travels to a central European financial centre to collect his brother’s corpse. The dead man had a management level job in banking, but his body is discovered with an anti- globalisation protest mask on its face. Analysis of the world situation is combined with elements of a detective thriller. The novel’s love affair is likened to a business deal: capital, profit and risk are equated with desire, hope and sorrow. This anti-capitalist metaphor is a typical theme of contemporary Finnish prose fiction.

Translated by David McDuff

Moomins, and the meanings of our lives

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

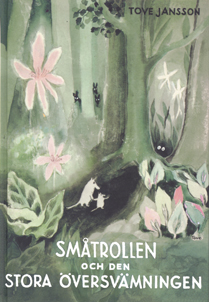

The first ever Moomin story, 1945

Tove Jansson’s Moomin books are widely cherished by children and adults alike. They are funny and charming yet haunting and profound. Lovable Moomintroll; practical and sensible Moominmama; spiky Little My; the terrifying yet complex monster, Groke – Jansson’s creations linger in the mind.

The first ever Moomin book – The Moomins and the Great Flood (Småtrollen och den stora översvämningen, 1945) – was published in the UK in October by Sort Of Books, but Jansson’s writing for adults is also achieving recognition in the English-speaking world.

A Winter Book, a selection of 20 stories by Jansson (Sort Of Books, 2006) was the trigger for a recent event on London’s South Bank. Along with journalist Suzi Feay and writer Philip Ardagh, I was invited to talk about Jansson’s work in general and about these stories in particular.

As Ali Smith notes in her fine introduction to the collection, the texts are ‘beautifully crafted and deceptively simple-seeming’. They are, as she puts it ‘like pieces of scattered light’. She also refers to the stories’ ‘suppleness’ and ‘childlike wilfulness’.

‘The Dark’, for example, offers an apparently random set of snapshots of childhood. Arresting images abound – swaying lamps over an ice rink, swirls in the pattern of a carpet that turn into terrible snakes – to create a tapestry of childhood. It’s like a dream: of ice and fire, fear and safety, a mixture that recalls the secure yet scary world of Moomin valley.

‘Snow’, too, conjures childhood fear. The house that features in this story is unhomely or uncanny, to refer to Freud, and seems haunted by the ghosts of other families. The story ends with the shared resolution between mother and child to return to a place of safety: ‘So we went home.’

Tove Jansson (1914–2001)

The combination of scariness and safety, of comfort and unease, is one of the things that makes Jansson (1914–2001) such a powerful writer, not only for children – although questions of security and fear might have especial resonance in early life – but also for adults, who continue to be haunted by the unknown, but also tempted by it.

The South Bank event also gave participants and audience the chance to talk about other works by Jansson. The Summer Book (Sommarboken, 1972) notably, is a delicate and deft evocation of a summer spent on an island.

The narrative charts the relationship between a grandmother and granddaughter, and at the same time probes such profoundly human questions as love and loss, hope and change and continuity. As always in Jansson, the descriptions are sharp and crisp, and the writing is at once spare and suggestive.

Novels like Fair Play (Rent spel, 1989) and The True Deceiver (Den ärliga bedragaren, 1982) reveal Jansson’s subversive, sly, and subtle sides, which sit alongside her playfulness, warmth, and humour to create a unique aesthetic. Fair Play is a book about the relationship between two women; it’s tender, funny and thoughtful. Never sentimental, it is nonetheless moving. And it’s quietly subversive in its matter-of-fact depiction of a same-sex relationship.

The True Deceiver is set in a snowbound hamlet. A young woman fakes a break-in at the house of an elderly artist, a children’s book illustrator, and a strange dynamic develops between the two women. It’s a book about being outside, about not belonging. The relationship between the women, which is never fully resolved or explained, is especially fascinating.

Jansson excels at showing the human need for both company and privacy, intimacy and autonomy. And her work is profoundly philosophical. In very light, nimble narratives, Jansson explores the meanings of our lives.

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012

13 December 2012 | In the news

Ulla-Lena Lundberg. Photo: Cata Portin

The winner of the 29th Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, worth €30,000, is Ulla-Lena Lundberg for her novel Is (‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms), Finnish translation Jää (Teos & Schildts & Söderströms). The prize was awarded on 4 December.

The winning novel – set in a young priest’s family in the Åland archipelago – was selected by Tarja Halonen, President of Finland between 2000 and 2012, from a shortlist of six.

In her award speech she said that she had read Lundberg’s novel as ‘purely fictive’, and that it was only later that she had heard that it was based on the history of the writer’s own family; ‘I fell in love with the book as a book. Lundberg’s language is in some inexplicable way ageless. The book depicts the islanders’ lives in the years of post-war austerity. Pastor Petter Kummel is, I believe, almost the symbol of the age of the new peace, an optimist who believes in goodness, but who needs others to put his visions into practice, above all his wife Mona.’

Author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born 1947) has since 1962 written novels, short stories, radio plays and non-fiction books: here you will find extracts from her Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010). Among her novels is a trilogy (1989–1995) set in her native Åland islands, which lie midway between Finland and Sweden. Her books have been translated into five languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (researcher Janna Kantola, teacher of Finnish Riitta Kulmanen and film producer Lasse Saarinen) shortlisted the following novels: Maihinnousu (‘The landing’, Like) by Riikka Ala-Harja, Popula (Otava) by Pirjo Hassinen, Dora, Dora (Otava) by Heidi Köngäs, Nälkävuosi (‘The year of hunger’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen and Mr. Smith (WSOY) by Juha Seppälä.

Fredrik Lång: Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman [From what is happiness. A Croesus novel]

4 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman

Av vad är lycka. En Krösusroman

[From what is happiness. A Croesus novel]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 221 p.

ISBN 978-951-523-002-7

€20.25, hardback

What is happiness? According to the Western thought, happiness is to have, to own, and whenever possible to get even more – it is interesting to find out what our forefathers thought about the question before it was answered. This is precisely what Fredrik Lång does in this novel, the best since the ancient-inspired Mitt liv som Pythagoras (‘My life as Pythagoras’, 2005). Lång describes the Lydian king Kroisos, the richest man of his day, and his attempt to overthrow the wise Greek Solon’s idea that moderation and a contemplative lifestyle lead to happiness. Even if the driving force behind this novel is philosophical, it is brought alive with graphic depictions, extravagant battlefield scenes, intrigue and heartrending romance. Lång’s narrative is often ironic or comical, yet it still manages to emphasise the hard lives of its characters and the complete and utter inequality between master and slave, rich and poor, man and woman. Despite the immersion in the past, it is his own time Lång writes about, sometimes via shameless anachronism, sometimes subtle hints.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Robert Åsbacka: Samlaren [The collector]

30 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Samlaren

Samlaren

[The collector]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 191 p.

ISBN 978-951-52 3001-0

€22.50, hardback

Violence and darkness have always played an important role in the novels Robert Åsbacka (born 1961) writes, but up until now they have been accompanied by mitigating factors, tenderness, and warmer tones. His new novel is a dark story which goes deeper into the wound than any of the earlier novels. Tom, lonely boy and fatherless victim of bullying in a children’s world where adults neither see nor help, gets to know the young couple next door, Bo and Viola. Bo is friendly, Viola is nice and beautiful, and their life seems, for a while, to be the picture of a better future for a boy to grow up to, a life with a car, girlfriend, breathing room. But Åsbacka mercilessly reveals the grim truth about Bo and Viola; violence exists in the adult world too. In all its horror, Samlaren is one of the autumn’s best novels; the only comfort comes in the form of Åsbacka’s style, and well balanced and meticulous depictions. Åsbacka is careful in his choice of depictions, and he knows how to make sure the image remains etched into the reader’s memory.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Finlandia Prize for Fiction candidates 2012

23 November 2012 | In the news

The candidates for the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012 were announced on 15 November. They are Riikka Ala-Harja, Pirjo Hassinen, Heidi Köngäs, Ulla-Lena Lundberg, Aki Ollikainen and Juha Seppälä.

Their novels, respectively, are Maihinnousu (‘The landing’, Like), Popula (Otava), Dora, Dora (Otava), Is (‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms), Nälkävuosi (‘The year of hunger’, Siltala) and Mr. Smith (WSOY).

The jury – researcher Janna Kantola, teacher of Finnish Riitta Kulmanen and film producer Lasse Saarinen – made their choice out of ca. 130 novels. The winner, chosen by Tarja Halonen, who was President of Finland between 2000 and 2012, will be announced on 4 December. The prize, awarded since 1984, is worth 30,000 euros.

The jury’s chair, Janna Kantola, commented: ‘One of this year’s recurrent themes is the Lapland War [of 1944–1945]. Writers appear to be pondering the role of Germany in both the Second World War and in contemporary Europe. Social phenomena are examined using satire; the butt is the birth and activity of extremist political movements. Economics, the gutting of money and market forces, are present, as in previous years, but now increasingly with a sense of social responsibility.’

Popula deals with people involved in a contemporary populist political party. Dora, Dora describes Albert Speer’s journey to Finnish Lapland in 1943. Nälkävuosi depicts the year of hunger in Finland, 1868. Is takes place in the Finnish archipelago of the post-war years. Mr. Smith portrays greed and the destructive power of money both in Russian and Finnish history as well as in contemporary Finland. Maihinnousu, set in Normandy, depicts a child’s serious disease in a family that is going through divorce.

Aki Ollikainen: Nälkävuosi [The year of hunger]

23 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Nälkävuosi

Nälkävuosi

Helsinki: Siltala, 2012. 139 p.

ISBN 978-952-234-089-4

€32.90, hardback

Finland, winter 1867, famine. The historical framework of this first novel by Aki Ollikainen (born 1973) is barren and the twists of the plot, almost without exception, are dark. The novella weaves together two stories: the poor people of the countryside live hand to mouth, whereas city businessmen, the brothers Teo and Lars Renqvist, agonise about their love problems in their well-heated houses. Of a family of four that sets out from the countryside on a begging mission, only one lives to see the following spring and the melting of the snow. The beast in people leaps forth: when there is no longer anything left to lose, humanity, an unnecessary burden, is trampled into the mud. The whiteness of the endless winter becomes the colour of hunger and of death. Ollikainen’s brief and tragically beautiful novel – which won the Helsingin Sanomat Prize for first works in November – tells its cruel tale with a warmth that is not in conflict with the events it describes. When the roads of city gents and country people entwine, humanity wins, light dawns.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Kaj Korkea-Aho: Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan [The grass is darker on the other side]

9 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan

Gräset är mörkare på andra sidan

[The grass is darker on the other side]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012, 425 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2999-1

€22.40, hardback

Finnish translation:

Tummempaa tuolla puolen

Helsinki: Teos & Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 436 p.

Suomennos [Translated by]: Laura Beck

ISBN 978-951-851-482-7

€28.40, hardback

Benjamin’s life is turned upside down when he, in despair over his fiancée’s death, discovers things he perhaps didn’t want to know. A photograph taken by a speed camera minutes before the car crash shows that Sofie wasn’t alone in the car. A group of childhood friends reunite for Sofie’s funeral; dark secrets from the past which had until now lain hidden away and unexplained start to come out. What really happened when one of the villagers died in mysterious circumstances? Who murdered little Sidrid Ask? The enormous dark shadow filling people with chilling terror – is it Raamt, evil himself, walking amongst them again? Which should they be more scared of, the supernatural evil or the everyday and human that seems to be all around them? In his second novel the former television presenter and comedian Kaj Korkea-aho (born 1983) writes with great detail and a finely tuned ability to pitch his language. His novel is filled with fear, evil and supernatural phenomena, but at the same time with humour and warmth. The intrigue advances at an addictively fast pace. Korkea-aho takes his novel from biting parody, via horror to a beautiful yet serious depiction of the power of friendship.

Translated by Claire Dickenson

Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is [Ice]

1 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Is

Is

[Ice]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 364 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2987-8

€ 23.25, hardback

Finnish translation:

Jää

Helsinki: Teos & Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 365 p.

Suomennos [Translated by]: Leena Vallisaari

ISBN 978-951-851-475-9

€ 28.40, hardback

Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born on the island of Kökar, Åland, 1947) is already the author of an extensive list of award-winning books, but her new novel Is (‘Ice’) is undoubtedly her most impressive work. It is written in a classic genre, an epic bound by time and place, in which the sensitive portrayal of characters and details takes a strongly ethical direction. Is describes life in a outer archipelago in the late 1940s, where a young priest arrives with his small family. In his calling he is a man devoted to the Word: helpful, friendly, naïvely unsuspecting in his philanthropy. His wife is cast in a different mould: a practical, at times apparently emotionless survivor, who runs a large household single-handed. The couple becomes part of the community of small islands and its harsh living conditions. At times the ice that shuts the island off from the outside world melts into freedom, only to lapse again into a cold that rudely limits human destinies. Barren nature and a community spirit reverting to early Christianity take the measure of each other in the novel’s dramatic events.

Translated by David McDuff

Katri Lipson: Jäätelökauppias [The ice-cream vendor]

25 October 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Jäätelökauppias

Jäätelökauppias

[The ice-cream vendor]

Helsinki: Tammi, 2012. 300 p.

ISBN 978-951-31-6868-1

€ 36.20, hardback

The Finnish novel of the 2000s has been successfully set in other cultures. Like Kristina Carlson and Sofi Oksanen, Katri Lipson went her own way as an author in her award-winning debut novel Kosmonautti (‘Cosmonaut’, 2008), which was set in the Soviet Union of the 1980s. In her second novel Lipson (born 1965), who works as a doctor in Helsinki, portrays life in post-war Czechoslovakia. The novel begins with the making of a film. The director wants to work without a script, which is only in her head. The filming proceeds chronologically, so that the actors will not anticipate what happens to the characters in the future. The film tells the story of a man and a woman’s flight from danger in 1942. Although they do not know each other, they pretend to be a married couple and hide in the countryside. What will be their fate during the war and afterwards is left to the reader; the characters can be combined with those appearing in the novel’s later stages, in the 1960s and even the 1980s. Lipson’s technique boldly breaks with the supremacy of narrative and calls into question the construction of historical truth.

Translated by David McDuff

Sofi Oksanen: Kun kyyhkyset katosivat [When the doves disappeared]

9 October 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kun kyyhkyset katosivat

Kun kyyhkyset katosivat

[When the doves disappeared]

Helsinki: Like, 2012. 365 p.

ISBN 978-952-01078-19

€ 27.90, hardback

Four years after the huge national and international success of her third novel Puhdistus (Purge, 2008, now translated into 38 languages), Sofi Oksanen has published a new novel to the accompaniment of trumpets and drums – a launch cruise to Tallinn, Estonia, workshops and public readings. The Finnish film version of Puhdistus received its world premiere at the same time. Oksanen has earned her star status as a writer, but Kun kyyhkyset katosivat is not as good as its predecessor. The story of Estonian freedom fighter (‘Forest Brother’) Roland and his cousin Edgar, an opportunist who manoeuvres his way through the Nazi and Soviet occupations of Estonia from 1941 until the apparent liberalisation of the 1960s, is thin and fragmentary. The language and style are uneven and diffuse, while Edgar’s chameleon-like shifts of identity from pro-German sympathies through Siberia to complicity with the KGB deserve to be more carefully explored. While the book’s themes are unquestionably authentic and relevant, they don’t really blend together into a moving novel in the way that Puhdistus does.

Translated by David McDuff