Tag: Finnish society

Eveliina Talvitie: Keitäs tyttö kahvia. Naisia politiikan portailla [Put the kettle on, girl. Women on the ladder of politics]

23 May 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Keitäs tyttö kahvia. Naisia politiikan portailla

Keitäs tyttö kahvia. Naisia politiikan portailla

[Put the kettle on, girl. Women on the ladder of politics]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2013. 332 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-39485-4

€29, hardback

In 1906 Finnish women were the first in Europe to obtain the right to vote, and Finland, like the other Nordic countries, is viewed as a model of equality. Journalist and author Eveliina Talvitie examines the role of women in politics. She has interviewed seventeen Finnish female politicians, more than half of whom have served as cabinet ministers. Among them are former President Tarja Halonen and Elisabeth Rehn, who has long worked on international assignments – between her and the youngest politician in the book there is a 52-year age gap. The interviewees describe the different aspects of the progress of their careers, their successes and setbacks. At the end of each chapter the author considers the challenges faced by female politicians from a particular point of view, backing up her conclusions with supplementary interviews. Not all of the politicians in the book have been handicapped because of their gender, but the work clearly demonstrates that, even in a relatively egalitarian country, female politicians are still treated differently from men, and their career paths can often be more difficult than those of their male colleagues.

Translated by David McDuff

Jukka Sarjala: Kotomaamme outo Suomi [Finland, our strange homeland]

4 April 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kotomaamme outo Suomi

Kotomaamme outo Suomi

[Finland, our strange homeland]

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 264 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-440-7

€ 27, paperback

Jukka Sarjala, ex-director general of the Finnish National Board of Education and bibliophile, is the author of several works of non-fiction, mainly in the field of history. In this book he focuses on the phenomena and events that characterised early twentieth-century Finland, some of them rather peculiar. In a couple of dozen chapters written in a humorous and conversational style the author does not conceal his own opinions, for example, on the foolishness of politicians. Much of the writing is devoted to the era of Finnish independence and the Finnish Civil War, as well as to episodes from political history, such as the story of the attempt to import to the newly independent country a German-born prince as King of Finland, the vagaries of the political far right and far left, the recruitment of Finnish Reds into the British Army – and the horse that gave rise to a small rebel movement. Sarjala draws many fascinating portraits of early twentieth-century figures, for example the utopian socialist Matti Kurikka and the founder of a party that in some ways anticipated the present-day True Finns [Perussuomalaiset], the talkative politician Veikko Vennamo (1913–1997). Although the book lacks footnotes and a bibliography, it demonstrates its author’s extensive reading.

Translated by David McDuff

On the road, in the world

21 March 2013 | Reviews

In Romani dress: Finnish Romani women still wear their traditional velvet skirts (which weigh 5-8 kilos). Photo: Topi Ikäläinen, 1983

Suomen romanien historia

[A history of Finland’s Romani people]

Toimittanut [Edited by] Panu Pulma

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (the Finnish Literature Society), 494 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-364-7

€57, hardback

The Romani people set out from India around a thousand years ago; there are those who even claim that they originated in Egypt long before that. This latter account was favoured among the Romani in Europe, and so their leaders took to styling themselves the Dukes of ‘Egypt Minor’ or ‘Little Egypt’.

The Romani of Europe are generally considered to have come from northern India in the 15th century. They arrived in Finland – which at that time was part of Sweden – in 1512.

Five hundred years later, it seems a fitting time to publish Suomen romanien historia, a volume edited by Panu Pulma, PhD, a university lecturer in Finnish and Nordic history, with chapters contributed by a total of 14 additional experts.

The Romani who reached Stockholm, also in 1512, were said to be from ‘Egypt Minor’. This purported connection with Egypt is the origin behind the English word gypsy. The Swedish word zigenare (related to the German Zigeuner) did not come into use until the 17th century. More…

Maailman paras maa [The best country in the world]

14 March 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Maailman paras maa

Maailman paras maa

[The best country in the world]

Toim. [Ed. by] Anu Koivunen

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 255 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-347-0

€ 37, paperback

In this book twelve writers, representing various fields of research, ponder Finland and Finnishness from the viewpoint of history, ethnology, society, culture and economics. Finland-Swedishness and the relationship between Finns and Russians, the need of Finns to defend their participation in the Second World War in alliance with Germany as a ‘separate war’, and the nostalgia related to lost Karelia. The articles deal with Finland facing economic challenges, attitudes towards foreign beggars and self-critical Finnish opinion pieces. They also take a look at Finnish man as portrayed in the classic novel Seitsemän veljestä (‘The seven brothers’, 1870, by Aleksis Kivi) and in a recent prize-winning film about men talking in the sauna about their feelings, and discuss the relationship of the two national languages, Finnish and Swedish. Well-written and original articles question truisms and challenge the reader contemplate his or her own relationship with Finnishness.

Umayya Abu-Hanna: Multikulti. Monikulttuurisuuden käsikirja [Multiculti. A handbook of multiculturalism]

17 January 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Multikulti. Monikulttuurisuuden käsikirja

Multikulti. Monikulttuurisuuden käsikirja

[Multiculti. A handbook of multiculturalism]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2012. 229 p.

ISBN 978-952-234-064-1

€ 24.90, paperback

Umayya Abu-Hanna is a Palestinian-born journalist and writer who lived in Finland for a long time and is now resident in Amsterdam. She has received awards for her work as an expert on multiculturalism. Finland’s migrant population is constantly growing, and Multikulti is aimed particularly at workers in Finland’s cultural sector; it may also be useful to others as a polemical handbook. Written in fluent, if flawed, Finnish, it contains practical instructions, tasks, and themes for discussion for those who deal with migrants. On the basis of her own experience and that of others Abu-Hanna shows clearly how migrants from outside Europe, especially Africans and Muslims, but also those who come to Finland from closer to home, encounter prejudice, racism, an involuntary lack of understanding and a lack of ‘cultural literacy’. Faults are evident at all levels of society, including the state’s cultural administration.

Translated by David McDuff

Good school, bad pupils, or vice versa?

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

Number one: Finland. The Pearson analysis, 2012

Finland is used to feeling pretty good about itself when it comes to education. In the widely respected PISA tests – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s exams in science and literacy – Finnish schoolchildren have, since the turn of the century, been outperforming most of their peers.

A shock came in 2009 when the tests revealed that Finnish kids were only third-best at reading, and sixth in maths; but by this time they were competing against the newly participating Asian countries, with their huge concentration on education.

Now, however, a new league table, drawn up by the education publishers Pearson, places Finland right at the top (2006–2010, 40 countries). Second place is held by South Korea; third is Hong Kong. The Pearson analysis uses a broader set of criteria, using not just test results but broader measures such as how many people go to university. In a result that is causing some puzzlement in the United Kingdom, Britain is rated sixth. Entirely, say critics, because British universities are so easy to get into.

The results are indeed flattering to Finland – but Finnish children’s motivation to learn is among the weakest in the survey’s countries. In reading, mathematics and the sciences Finns’ attitudes and application were low. It looks as if Finnish children consider school a place to hang out with their friends, not a place for teaching and learning. Countries where competition is stronger breed different attitudes.

So here’s the Finnish paradox: kids here hate school – yet still end up at the top of the list.

Must be something in the water.

Pilvi Torsti: Suomalaiset ja historia [The Finns and history]

21 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Suomalaiset ja historia

Suomalaiset ja historia

[The Finns and history]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2012. 303 p., ill .

ISBN 978-952-495-264-4

€37, paperback

Dr Pilvi Torsti’s book is based on a project aimed at finding out through extensive interviews what ordinary Finns think of Finland’s history (especially in the period of independence since 1917), and how important it is to them, rather than how much they know about it. The large majority of the respondents believe that history forms part of general knowledge and also explains the present. They also attached importance to their own family history, while Finnish history was seen as a story of progress. History undertaken as a hobby is more common in Finland than in some comparable countries. When asked about the most important issues in the country’s history, the education system came top of the list in more than 75 per cent of the responses, and the Winter War (1939–40) and universal suffrage (1906) in more than half. The comprehensive presentation of research data and conclusions is leavened by the interviewees’ statements, as well as by drawings. More information about this many-faceted study can be found on the project’s website.

Translated by David McDuff

Mind the gaffe

14 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

Celebrating Finnish Independence Day is a serious business involving lots of handshakes and plenty of pitfalls for the unwary, observes columnist Jyrki Lehtola. But luckily there’s plenty of fun to be had for ordinary Finns in complaining about it all

When Finland makes the news, it’s usually because of a national tragedy or something odd we do. The latter ripe fodder for filling the blank pages of the international media on slow news days includes such things as the Finnish penchant for competitions in such sporting events as Wellington boot /mobile phone tossing (saappaan- / kännykänheitto) and wife carrying (akankanto).

We have another odd national tradition, although it has never received as much international recognition as the fact that we carry our wives competitively. This time- honoured custom repeats annually on the sixth of December, when we close our shops and barricade ourselves gloomily within our homes. Its name is Independence Day. More…

Markku Kuisma & Teemu Keskisarja: Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012 [The infallible ones. The story of the great bank war and Finland’s commercial banks, 1862–2012]

13 December 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012

Erehtymättömät. Tarina suuresta pankkisodasta ja liikepankeista Suomen kohtaloissa 1862–2012

[The infallible ones. The story of the great bank war and Finland’s commercial banks, 1862–2012]

Helsinki, WSOY, 2012. 496 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-39228-7

€ 38.80, hardback

Historians Markku Kuisma and Teemu Keskisarja’s lively book tells the story of Finland’s commercial banks, from the establishment of the first one in 1862. A recurrent theme in the book is the competition between the two largest. With their relations to and allies in the business world the banks have had an important social and political influence in the country. The commercial banking institutions have had more prominence than others, and the directors have often been strong personalities. Most of the emphasis in the book is placed on the final decades of the 20th century. In the 1980s the financial markets were deregulated, and the boom of the ‘crazy years’ of the bank war was accelerated by share trading and cornering. In 1995 the recession caused by the banking crisis led to the merger of the two largest commercial banks. A few years later this new institution merged with a Swedish one, and the large new bank Nordea subsequently expanded to neighbouring countries. The age of large national commercial banks in Finland was over.

Translated by David McDuff

Form follows fun

4 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

The house that the artist built: ‘Life on a leaf’ (2005–2009, Turku). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Jan-Erik Andersson: Elämää lehdellä [Life on a leaf]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2012. 248 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5872-82-4

€42, hardback

‘I am Leaf House –

root house, sky house.

Enter me, be safe

And wander, dream.

The artist’s I is all our eyes….’

In the garden: red ‘apple’ benches designed by the English artist Trudy Entwistle. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

We all live – exceptions are really rare – in cubes. Not in cylinders or spheres, let alone in buildings of organic shapes like flowers or leaves; and houses in the shape of a shoe, for example, belong to the fairy-tale world, or perhaps to surrealism.

Artist Jan-Erik Andersson wanted to build a fairy-tale house in the shape of a leaf, and that is what he did (2005–2009), together with his architect partner Erkki Pitkäranta. Instead of the geometry of modernist architecture, he is inspired by the organic forms of nature.

Andersson’s house project, entitled ‘Life on a leaf’, also became an academic project, resulting in a dissertation at Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and now a book, including a detailed journal of the building process itself. The artist was at first advised, by a professor of architecture, not to proceed with his building project – he wouldn’t ‘like living in the house’, he was told. More…

See the big picture?

9 November 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Details from the cover, graphic design: Työnalle / Taru Staudinger

In his new book Miksi Suomi on Suomi (‘Why Finland is Finland’, Teos, 2012) writer Tommi Uschanov asks whether there is really anything that makes Finland different from other countries. He discovers that the features that nations themselves think distinguish them from other nations are often the same ones that the other nations consider typical of themselves…. In Finland’s case, though, there does seem to be something that genuinely sets it apart: language. In these extracts Uschanov takes a look at the way Finns express themselves verbally – or don’t

Is there actually anything Finnish about Finland?

My own thoughts on this matter have been significantly influenced by the Norwegian social scientist Anders Johansen and his article ‘Soul for Sale’ (1994). In it, he examines the attempts associated with the Lillehammer Winter Olympics to create an ‘image of Norway’ fit for international consumption. Johansen concluded at the time, almost twenty years ago, that there really isn’t anything particularly Norwegian about contemporary Norwegian culture.

There are certainly many things that are characteristic of Norway, but the same things are as characteristic of prosperous contemporary western countries in general. ‘According to Johansen, ‘Norwegianness’ often connotes things that are marks not of Norwegianness but of modernity. ‘Typically Norwegian’ cultural elements originate outside Norway, from many different places. The kind of Norwegian culture which is not to be found anywhere else is confined to folk music, traditional foods and national costumes. And for ordinary Norwegians they are deadly boring, without any living link to everyday life. More…

Do you speak my language?

23 August 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

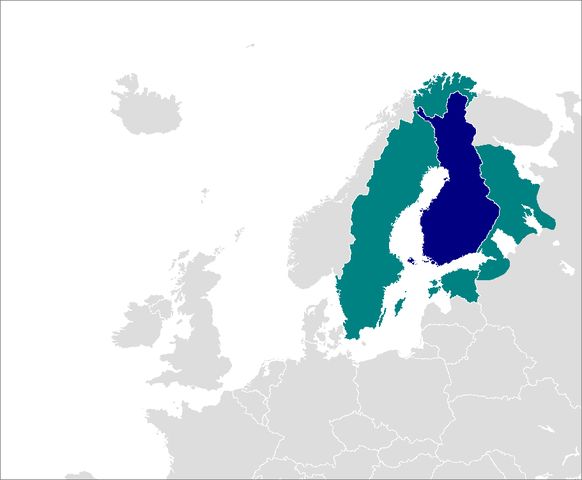

Finnish spoken outside Finland: Sweden (west), Estonia (south), Karelia/Russia (east), Norway (north). Illustration: Zakuragi/Wikipedia

Finland has two official languages, Finnish and Swedish. Approximately five per cent of the population (290,000 Finns) speak Swedish as their native language. All Finns learn both languages at school, and students in higher education must prove they have an adequate knowledge of the other mother tongue. But how do native speakers of Finnish cope with what is, for many of them, a minority language that they will never need or even wish to use? We take a look at bilingual issues – and a new book devoted to them

‘In many parts of the world, language can be a fiery and divisive issue, one that pits the powerless against the powerful, the small against the big. The Basques battle the Spanish. The Flemish tussle with the Walloons. The Québécois scuffle with the rest of Canada.’

That is how Lizette Alvarez illustrated her theme in her article ‘Finland Makes Its Swedes Feel at Home’, published in the New York Times in 2005.

In Finland, language has been a fiery issue at times, though things have cooled down a bit since the early 20th century. The use of Finnish as a written language dates back to the 16th century, but the territory of Finland was part of the Swedish Empire until 1809. Swedish was spoken by the nobility as well as most of the peasant class – the mechanism of the state did not serve Finnish-speaking peasants or other segments of the population in Finnish. More…

Two to tango

3 August 2012 | This 'n' that

Tango: less romantic up north? Finns love it anyway. Photo: Orfeuz, Wikimedia

Picture the scene: it’s August, and the nightless days of midsummer have given way to darkening evenings. Candles are lit, and minds turn to the winter ahead.

The berries of the rowan trees are already turning bright scarlet and the purple rosebay willow herb catches the last of the sunset. From an outdoor dance floor across the meadow drift the melancholy strains of… the Finnish tango.

(The YouTube insert is from the film Tulitikkutehtaan tyttö [‘The matchbox factory girl’, 1990], by Aki Kaurismäki, featuring the actress Kati Outinen. Satumaa [‘Wonderland’ by Unto Mononen] is sung by Reijo Taipale.)

Cheesy as it is, we confess we have a liking for this most northerly cousin of the fiery Argentine original. So, it seems, does the BBC Magazine, in a recent article, Mark Bosworth goes to witness the traditional Tango Festival in Seinäjoki. Check it out. More…

Summer madness

27 June 2012 | Non-fiction, Tales of a journalist

Illustration: Joonas Väänänen

In the endlessly long days of the brief Nordic summer, what could be better than to go on a bender? Jyrki Lehtola explores a quaint Finnish custom

In Finland it’s cold and dark for nine months of the year. We spend the other three months drunkenly praying that tomorrow it might be warmer and lighter – and sometimes it is.

From the perspective of the national psyche, you’d think we might have learnt to live with the cold and the dark. We might have dealt with it and turned it into something useful to us and to our continued survival. Sadly though, this isn’t quite the case. For nine months we sit indoors staring at the television, complaining that there’s never anything worth watching and waiting for those three months to come so that we can go outside again.

And when we finally get outside, we go mad. No longer are we a silent, anxious people. Well, we are, but we pretend we’re a different kind of people: one that spends its time chattering joyfully on the beach, dancing, enjoying life, discussing, debating, participating, sharing.

The arrival of summer makes us go mad. By the end of June, this silent, anxious, suicidal nation has turned into the number one samba carnival of Northern Europe. More…

Getting by

18 May 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

To school: children on the march – no buses or taxis in the Finnish countryside after the war. Photo: the cover of Kauaksi kotoa

Kauaksi kotoa. Muutoksen sukupolvi kertoo

[Far from home. Stories of the change generation]

Toim. [Ed. by] Anja Salokannel & Kaija Valkonen

Helsinki: Kirjapaja, 2012. 320 p.

ISBN 978-952-247-291-5

€32.90, hardback

The post-war period in Finland was a time of hope and reconstruction, of procreation and tough, grey heroism. Finland picked itself up by the bootstraps, as fathers who had been ‘driven mad in the war’, who took to drink or spat blood because they had shrapnel in their lungs, built veterans’ houses around the small towns and cleared fields in the backwoods. More than 83,000 men were killed in the wars (Winter War 1939–1940, Continuation War 1941–1944).

Mothers worked like men. The baby boomers – the demographic peak which consists of those born between the war years and 1950 (in 1946–1949 more than 100,000 babies were born each year, compared to some 60,000 in 2011) – had to be fed and clothed and educated for a better and more prosperous future.

Now the baby boomers have started to retire. Editors Anja Salokannel and Kaija Valkonen (baby boomers themselves) have compiled the book Kauaksi kotoa. Muutoksen sukupolvi kertoo (‘A long way from home. Stories of the change generation’), in which 21 men and women talk about their lives during the decades of change. More…