Tag: Finnish history

Jonna Pulkkinen: Kieltolaki. Kielletyn viinan historia Suomessa. [Prohibition. A history of prohibited liquor in Finland.]

29 June 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Jonna Pulkkinen

Jonna Pulkkinen

Kieltolaki. Kielletyn viinan historia Suomessa. [Prohibition. A history of prohibited liquor in Finland.]

Helsinki: Minerva, 2015. 213pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-312-112-6

€32,90, hardback

Prohibition of the making and selling of strong liquor was in force in Finland between 1919 and 1932. In this approachable book, the journalist and non-fiction writer Jonna Pulkkinen charts Finnish attitudes to alcohol over the ages and describes the origin and effects of prohibition. Total abstinence was popular in Finland in the second half of the 19th century, and was adopted in particular by the working class. Limits on alcoholic consumption were first imposed as early as the First World War. When a prohibition law that had been passed a couple of years earlier came into effect in newly independent Finland in 1919, however, support had already begun to dwindle. Home stills proliferated, smuggling from abroad was considerable and broadly accepted, and enforcing the law was difficult. Pulkkinen has numerous interesting and even comical examples that flouted the law on prohibition. The law was broken in all social classes, the use of liquor and crime increased throughout the country, and taxation income on alcohol was lost. As public criticism grew, an advisory referendum was held in 1931, and as a result the prohibition law was abolished the following year.

Antero Holmila & Simo Mikkonen: Suomi sodan jälkeen. Pelon, katkeruuden ja toivon vuodet 1944-1949. [Finland after the war, 1944-1949. Years of fear, bitterness and hope.]

16 June 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Antero Holmila – Simo Mikkonen

Antero Holmila – Simo Mikkonen

Suomi sodan jälkeen. Pelon, katkeruuden ja toivon vuodet 1944-1949. [Finland after the war, 1944-1949. Years of fear, bitterness and hope.]

Helsinki: Atena, 2015. 2650., ill.

ISBN 978-952-300-112-1

€34, hardback

Finland lost the Winter War and the Continuation War that followed, to the Soviet Union, and was then forced to engage in the short Lapland War to expel its former allies, the Germans. The return to peace was not easy, as the historians Antero Holmila and Simo Mikkonen demonstrate in this highly readable book. Loss of territory meant finding homes for more than 400,000 evacuees elsewhere in Finland, and this was not achieved without difficulty. Soldiers were demobilised and had to redomicile themselves in ordinary life and work; there was a shortage of housing; and heavy war reparations were to be paid to the Soviet Union. Leading politicians accused of appeasing the Soviet Union during the war received prison sentences, which many people considered wrong. The work highlights the aspirations of the Communists and the internal fighting on the political left. The Communist party, which had been banned, returned to the political stage and was successful in the 1945 elections. The majority of the nation was fearful of the growth of influence of the Communists and, through them, the Soviet Union. However, the Social Democrats, competing with the Communists for workers’ votes, succeeded in gaining considerably more votes than the Communists as early as 1948. Although strikes and conflicts occurred, conditions settled down gradually towards the end of the 1940s and the nation began to get back on its feet.

Kai Häggman: Pieni kansa, pitkä muisti. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura talvisodasta 2000-luvulle. [Small nation, long memory. The Finnish Literature Society from the Winter War to the 21st century.]

16 June 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kai Häggman

Kai Häggman

Pieni kansa, pitkä muisti. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura talvisodasta 2000-luvulle. [Small nation, long memory. The Finnish Literature Society from the Winter War to the 21st century.]

Helsinki: SKS, 2015. 524pp., ill.

€48, hardback

The Finnish Literature Society, publisher of Books from Finland, is of unique importance as a collector of Finnish folk poetry and folk tradition, a publisher of literature and a promoter of research into the Finnish language and history; today it is known particularly as one of the most important publishers of the humanities. The historian Kai Häggman has published many works about publishing, and his new book, the third volume of a history of the Finnish Literature Society, describes events from the Second World War to the present day. Among other things, the book describes the Finnish Literature Society’s activities in conquered Eastern Karelia in what was then considered part of the Greater Finland, and its ideological development from narrow nationalism to the broader outlook of the post-war decades. In the late 20th century the generation that had lived through the war was replaced by younger people, and the study of the folk tradition embraced aspects of modern society; methods, too, were renewed. The book also casts light on relationships between Finnish scholars and those from kindred nations such as Estonia. Häggman gives a lively all-round view of the work of the Society as part of Finnish cultural history as a whole, emphasising the importance of the most important scholars, and not forgetting the occasional infighting.

Oldest Helsinki photograph

2 June 2015 | This 'n' that

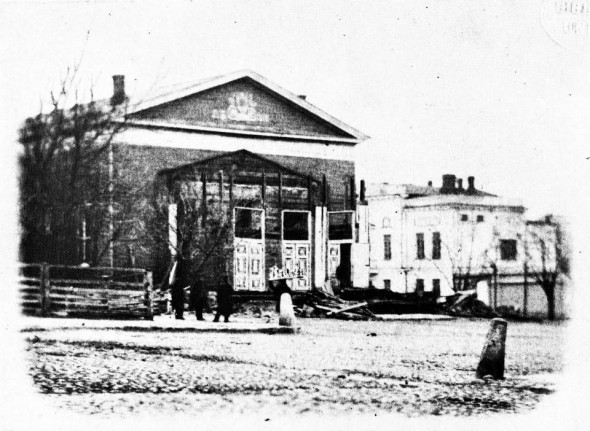

Old Helsinki: this image, taken in the Esplanadi park more than 150 years ago, shows the old theatre building, which was demolished in the 1850s. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Hidden in plain sight in Sven Hirn’s Kameran edestä ja takaa – valokuvaus ja valokuvaajat Suomessa 1839-1870 (‘Behind the camera and in front of it – photographs and photographers in Finland 1839-1870’), published more than 40 years ago, the image shows four men standing in front to the theatre designed by Carl Ludvig Engel in 1827 (and demolished when it became too small to accommodate the city’s enthusiastic theatre-going public in the 1850s). Unusually, in those days of slow shutter speeds, the photograph shows people, among them Carl Robert Mannerheim, father of the Marshal Mannerheim who was to lead Finland’s defence forces in the Second World War (third from left).

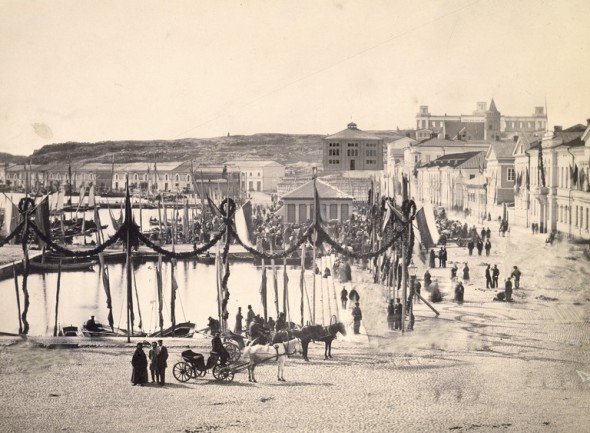

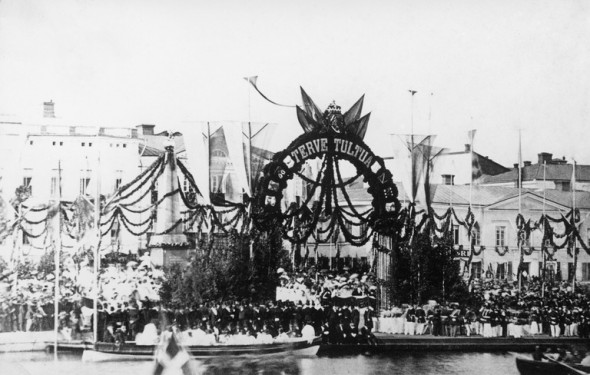

Among the other photographs published by Helsingin Sanomat are some images of Helsinki decked out in garlands awaiting the arrival of Tsar Alexander II to the capital of his autonomous grand duchy of Finland in July 1863.

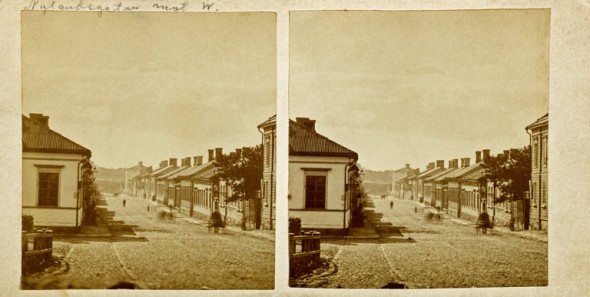

Other mid-century images show central Helsinki looking not unlike its present-day self. It’s only when the camera ventures outside the few blocks of the city centre that the view becomes more unfamiliar, the streets lined with one- and two-storey wooden houses.

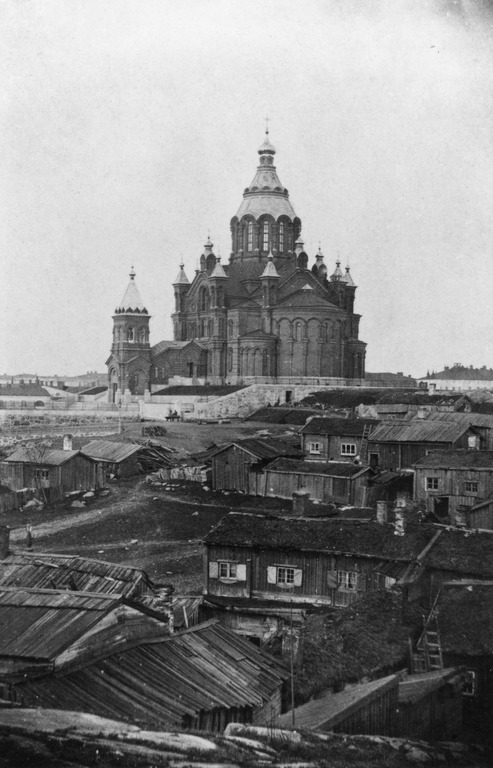

Most intriguing of all, however is a sequence of eighteen photographs taken in 1866 by one Eugen Hoffers from the top of Helsinki Cathedral. Helsingin Sanomat has linked them into a panorama with views of Suomenlinna fortress, the new Russian Orthodox Uspenski Cathedral, Books from Finland’s old publisher Helsinki University Library, and the burgeoning city beyond.

Imperial welcome: Helsinki is bedecked with flowers to welcome Tsar Alexander II on 28 July 1863. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Pomp and circumstance: elaborate floral tributes for the visit of Tsar Alexander II in 1863. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

New and old: the recently completed Uspenski Cathedral is surrounded by a shanty-town of tumbledown cottages in this image from 1868. Photo: Hoffers Eugen, Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Strange and familiar: this picture, from 1865, shows the Cathedral, the Senate and the University Library surrounded by low wooden buildings and unbuilt land. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

City of wood: beyond the familiar buildings of the few blocks of the then city centre, in this image from the 1860s, lie streets of modest one- and two-storey wooden houses. Photo: Gustaf Edvard Hultin , Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Hengen paloa & painettua sanaa. Renqvist-Reenpäät kustantajina 1815–2015. [A burning spirit & the printed word. The Renqvist-Reenpääs as publishers 1815-2015.]

25 May 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Juhani Salokannnel

Juhani Salokannnel

Hengen paloa & painettua sanaa. Renqvist-Reenpäät kustantajina 1815–2015. [A burning spirit & the printed word. The Renqvist-Reenpääs as publishers 1815-2015.]

Helsinki: Otava, 2015. 344 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-27838-2

47, hardback

Otava is currently Finland’s biggest book publisher, and is also active in the fields of newspapers, printing and bookshops. Almost from the beginning, the Reenpää (originally Renqvist) family has been at the head of this family business. Otava was founded in 1890, but 200 years ago a family forefather, Henrik Renqvist, who was studying for the priesthood began to publish religious books. In 1893 his grandson, Alvar Renqvist became Otava’s longstanding editorial director. Through his enthusiasm for Finnish-language literature and education, it was he who formed the basis for the publisher’s growth. His five sons and their sons guided the publishing house in the same spirit through some difficult times to the 21st century, and today the fifth generation is still at work there. The Reenpää family has had an important position in Finnish cultural life both as influential figures and as patrons. The writer Juhani Salokannel’s generously illustrated, well-designed work is based on wide source material and interviews with members of the Reenpää family and does not hold back from describing conflicts between some strong characters. The book is, indeed, a lively depiction of the Reenpääs’ history and work at Otava; a history of the publishing house as such has already been published.

Riitta Nikula: Suomalainen rivitalo. Työväen asunnosta keskiluokan unelmaksi. [The Finnish terraced house. From worker housing to middle-class dream.]

18 May 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Riitta Nikula

Riitta Nikula

Suomalainen rivitalo. Työväen asunnosta keskiluokan unelmaksi.

[The Finnish terraced house. From worker housing to middle-class dream.]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (The Finnish Literature Society), 2014. 252 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-568-9

€ 37, hardback

In her extensive, well-researched book on the semi-detached house, Professor Emerita of Art History Riitta Nikula describes the housing history of a typical well-to-do Finn as setting off from a flat in an apartment building, continuing to a terraced house and ending up in a house of his or her own. In Finland rivitalo (simply, ‘row house’) became increasingly popular in the 1960s and the majority of houses of this type were built during the two decades that followed. However, in her book Nikula concentrates on the years 1900–1960, the decades of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. In the 1930s Finland was eager to follow the renewal of town planning and architecture that was taking place elsewhere in Europe, and the rivitalo houses were part of the project of modernism. After the war the government funding system helped people to become owners of the properties they lived in, and the rivitalo became popular in growing towns. Prominent architects such as Eliel Saarinen, Alvar Aalto, Hilding Ekelund, Viljo Revell, and Kaija and Heikki Siren have all contributed to the development of this form of architecture. Nikula has travelled widely, in Europe and in Finland, researching this mode of living (the index of literature referred to alone fills seven large pages). The plentiful photographs and illustrations complement the text well.

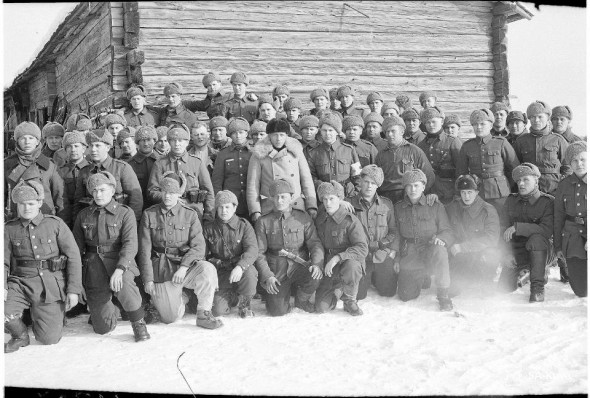

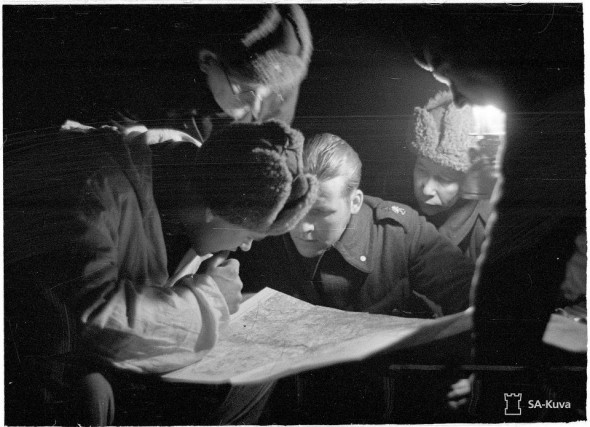

Images of war

5 May 2015 | This 'n' that

A soldier playing his accordion. Photo: SA-kuva

Between 1939 and 1944 Finland fought not one, but three separate wars – the Winter War (1939-45), the Continuation War (1941-44) and the Lapland War (1944-45).

We have become used to black-and-white images of the conflict, with their distancing effect. Among the 160,000 images in the Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive, however, are some 800 rare colour photographs from the Continuation War, which bring the realities of fighting much closer. The events pictured leap out of history and into the present. More…

Alpo Rusi: Etupiirin ote [The grip of the sphere of influence]

4 May 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Alpo Rusi

Alpo Rusi

Etupiirin ote [The grip of the sphere of influence]

Helsinki: Gummerus, 2014. 411p.

ISBN 978-951-20-9715-9

€34.90, hardback

In his work Etupiirin ote, the scholar, writer and former ambassador Alpo Rusi provides an interesting and polemical analysis of Finland’s foreign and security policies, particularly with regard to its neighbour, Russia / the Soviet Union. His premise is that from the 18th century onward Finland has, sometimes more broadly, sometimes more narrowly, formed part of the Russian sphere of influence. He gives a brief account of the end of the period of Swedish rule (until 1809) and that of Russian rule (1809-1917), as well as of the early decades of Finnish independence. The main emphasis of the book is on the period beginning with the Second World War. Rusi has a personal perspective on much recent history. He bases his evaluations on many diverse, sometimes controversial, sources and expresses strong opinions in his account, for example, of ‘Finlandisation’, Soviet influence on Finnish politics with its negative side effects. Rusi strongly criticises decision-makers who, as late as the 1980s and 1990s, believed in the desirability of trade with the east and the permanence of the Soviet Union, despite signals to the contrary. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland joined the European Union, but even as a member its attitudes towards, for example, Nato and Russia, have been problematic in many ways. Rusi ends his book on the theme of the Ukraine crisis, presenting his own proposal for the development of foreign and security policies.

Hannu Rautkallio: Mannerheim vai Stalin. Yhdysvallat ja Suomen selviytyminen 1939–1944 [Mannerheim or Stalin. The United States and Finland’s survival 1939–1944]

2 April 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Mannerheim vai Stalin. Yhdysvallat ja Suomen selviytyminen 1939–1944

Mannerheim vai Stalin. Yhdysvallat ja Suomen selviytyminen 1939–1944

[Mannerheim or Stalin. The United States and Finland’s survival 1939–1944]

Helsinki: Otava, 2014. 463 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-27394-3

€39.70, hardback

In his book political historian Hannu Rautkallio explores American attitudes towards Finland during the Second World War, when the country fought a Winter War and Continuation War against the Soviet Union. He makes use both of older materials and of American documents that have only become accessible to researchers in the 2010s. During the war years two trends were dominant; one was sympathetic to the aims of the Soviet Union, while the other took a hostile view of them. The US political leadership had refused to support Finland in the Winter War, but as the World War progressed the United States tended to understand the small country’s objectives and also the special nature of its alliance with Germany. The two states shared intelligence and there were a large number of secret contacts with Finland’s top government leadership. At the end of World War II, the United States communicated to the Soviet Union, which was dictating peace terms to Finland, that it was important Finland should remain an independent state. Rautkallio’s account keeps branching out along interesting side-tracks, but the book’s central theme captures the reader’s interest.

Translated by David McDuff

Ville Laamanen: Suuri levottomuus. Olavi Paavolaisen kultturinen katse ja matkat 1936-39 [A great restlessness. Olavi Paavolainen’s cultural gaze and travels 1936-1939].

2 April 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Ville Laamanen

Ville Laamanen

Suuri levottomuus. Olavi Paavolaisen kultturinen katse ja matkat 1936-39 [A great restlessness. Olavi Paavolainen’s cultural gaze and travels 1936-1939].

Turku: K&H, 2014. 346p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-29-5632-6

€32, paperback

The writer Olavi Paavolainen (1903-1964) was an important cultural critic in Finland in the years between the two World Wars. The historian Ville Laamanen’s doctoral thesis Suuri levottomuus explores how Paavolainen interpreted the encounter between the modern and totalitarianism. Laamanen examines Paavolainen’s journeys to National Socialist Germany and South America, where he was able to gain distance from Eurocentricity. Paavolainen published three books on the basis of these journeys, and these form the central sources for Laamanen’s research. The outbreak of the Winter War in Finland in 1939 prevented the publication of a fourth volume. This work would have focused on the Soviet Union, which at that point was little-known. The most important offerings of Laamanen’s book are the research results based on material from Russian archives which has hitherto remained unexamined. Paavolainen was not a communist, but was accorded VIP status in the Soviet Union and was able to gain a diverse view of the country. Laamanen also places Paavolainen in the broader cultural context of the 1930s. The book is at the same time a rigorous academic study and a well-written, gripping portrait of a still interesting Finnish intellectual during an important period.

The day peace came…

18 March 2015 | This 'n' that

Flags fly at half-mast in Helsinki. Photo: SA-Kuva

Seventy-five years ago, in the period known as the Phony War, while the rest of the world was preparing to fight, it looked as if hostilities were over for one country.

In the preamble to the Second World War, Soviet Union had attacked Finland on 30 November 1939, demanding substantial border territories for the protection of Leningrad. Germany had invaded Poland, and France and Great Britain had declared war; but the Nazi invasions of Norway and Denmark, Italy’s entry into the war, the Battle of Britain, Pearl Harbor, D-Day, Hiroshima, Nagasaki and all the other horrors of the Second World War were yet to come.

As the world watched, ‘plucky little Finland’, massively outnumbered in terms of both men and equipment but superior in morale, organisation and knowledge of the terrain, managed to keep the Red Army at bay for months – far longer than anyone had expected. Eventually, however, the Russians overcame Finnish border defences and the war ended on 13 March 1940. Now generally regarded by Finns as a defensive victory – Finland was not occupied by the Soviet Union – the peace treaty nevertheless imposed a heavy burden on Finland, which lost extensive territories in Karelia to the south and Salla to the north.

In the event, the war was far from over for Finland, which still had the Continuation War (1941-44) and the Lapland War (1944-45) to fight. But for the moment, the country was once more at peace.

To mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the war, the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper has published a selection of photographs of the day peace came.

Soldiers of the 69th infantry regiment are able to eat in peace at last. Photo: SA-Kuva

A tree felled across a road provides a makeshift border point. Photo: SA-Kuva

Soldiers in their white winter camouflage rest in Viipuri after peace is declared. Photo: SA-Kuva

Soldiers in Kuhmo, north-eastern Finland, inspect the new border line. Photo: SA-Kuva

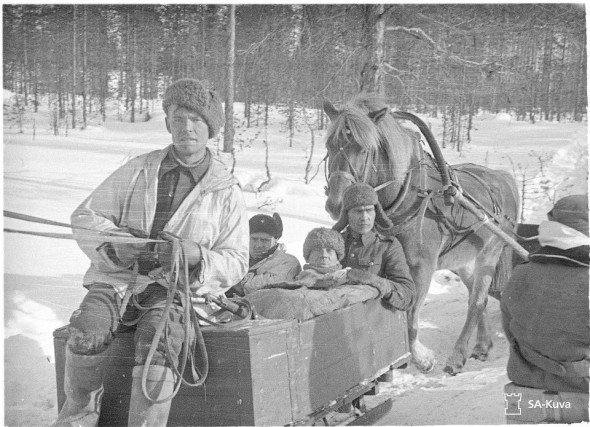

The last wounded soldiers are brought back by horse and cart from Saunajärvi. Photo: SA-Kuva

Petri Pietiläinen: Koirien Suomi. Kansanperinnettä ja historiaa [Dogs in Finland. Folk tradition and history]

12 March 2015 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Koirien Suomi. Kansanperinnettä ja historiaa

Koirien Suomi. Kansanperinnettä ja historiaa

[Dogs in Finland. Folk tradition and history]

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2014. 239 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-540-5

€32, hardback

Non-fiction writer Petri Pietilä is the author of the award-winning book Koirien maailmanhistoria (‘Dogs in world history’), which deals with the general cultural history of the dog. In the first half of this lively and fascinating new book he discusses the dog in Finnish folk tradition, while in the second half he gives an account of the history of the dog in Finland to the present day. Dogs have been domesticated in the North European region for thousands of years. In folk poetry, such as the national epic, the Kalevala, the dog is first and foremost a house guard and a partner in hunting. In Finnish folk tradition, the dog is viewed more leniently than in other countries, and stories about hellhounds are rare. Yet the attitude towards dogs in Finnish proverbs is not an exclusively positive one. Pietilä also says that the dog’s change of status has been linked to its becoming a helper and beloved pet, and today there are more than half a million of them in Finland. In addition, they are increasingly being used in various work and service roles. The book also presents the six Finnish dog breeds, and includes a dog name day calendar.

Translated by David McDuff

Iconic Inha

5 February 2015 | This 'n' that

From time to time we have featured the charismatic photographs taken of Helsinki by I.K. Inha (1865-1050) in 1908 – most recently in a book pairing Inha’s iconic images with contemporary photographs of the same scenes by Martti Jämsä (2009). Fifty-one of the images have now been made available online to the public for the first time on the Finnish Museum of Photography’s Flickr page.

Many of the scenes are so little changed that it’s a shock to see them peopled with behatted gentlemen and ladies in long skirts. Commissioned for Finland’s first travel guide, the photographs show the handsome buildings, parks and seafronts of a solidly bourgeois looking city that is still the capital of a Russian province, an autonomous Grand Duchy actively fostering the dream of independence that is to be realised nine years later, in 1917.

Student Union Building on Itäinen Heikinkatu (now Mannerheimintie). I.K. Inha, 1908.

Boys at Hietalahti harbour. I.K. Inha, 1908.

Herman Lindqvist: Kun Suomi oli Ruotsi [When Finland was Sweden]

18 December 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kun Suomi oli Ruotsi

Kun Suomi oli Ruotsi

[When Finland was Sweden]

(original Swedish title: När Finland var Sverige, 2013)

Suom. [Translated from Swedish by] Heikki Eskelinen

Helsinki: WSOY, 2014. 497 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-0-40491-1

€44, hardback

The Swedish historian and journalist Herman Lindqvist is the author of dozens of popular non-fiction books. When Finland was Sweden is primarily intended for Swedish readers – an overview of the period when Finland was part of the Swedish kingdom – and it is partly based on new research. Finland became an integral part of the western neighbouring country in stages – including armed force – a process that was complete by the beginning of the fourteenth century. It remained an eastern borderland of the Kingdom of Sweden until the year 1809. The period was marked both by the rise of Sweden in the 16th century to become a great Baltic power and its decline in that role a hundred years later. Lindqvist connects up the different stages of Finland’s absorption into Sweden in a colourful and lively way. He shows how the influences went in both directions between the western and eastern part of the kingdom; the influence of the Finns could be seen both on the battlefields and in politics. The traces of the long time the two countries spent together are still visible today in both, thought in Finland they are stronger than in Sweden.

Translated by David McDuff

Mirkka Lappalainen: Pohjolan Leijona. Kustaa II Aadolf ja Suomi 1611–1632 [Lion of the North. Gustavus Adolphus and Finland, 1611–1632]

3 December 2014 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Pohjolan Leijona. Kustaa II Aadolf ja Suomi 1611–1632

Pohjolan Leijona. Kustaa II Aadolf ja Suomi 1611–1632

[Lion of the North. Gustavus Adolphus and Finland, 1611–1632]

Helsinki: Siltala, 2014. 321 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-952-234-242-3

€31.50, hardback

The book presents a diverse and vivid history of the reign of Gustavus Adolphus – possibly the most important ruler in Swedish history – his era and his impact on Finland. When he rose to the throne at the age of just 17 in 1611, Finland was a strategically important region because of the threat posed by Russia and Poland. Among other things the king organised a meeting of representatives of the estates in Finland, the Regional Parliament of 1616 – even though he felt distrust of the Finnish people, who had supported the Polish King Sigismund, who had sought the Swedish crown. When the threat from the East had been repelled, Finland remained as a marginal corner of the world, which mainly provided taxes and soldiers. In 1630 the King, as a Lutheran soldier of faith, took his troops to Germany to fight in the Thirty Years War, and fell in 1632. However, in the period described the Swedish state, with Finland as a part of it, became a centralised state led by the King and his Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, a system of government that was one of the most efficient in Europe. Lappalainen received the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014 for her book.