Tag: education

Not joined up

19 February 2015 | In the news

Photo: Brad Flickinger / CC BY 2.0

The news that Finnish schools are to stop teaching cursive writing, in favour of a new emphasis on touch typing and the most efficient way of composing a text message, has been widely reported in the British press.

But not in our household.

With three children – aged 13, 9 and 6 – all struggling, to a greater or lesser degree, to make sense of the curlicues of joined-up writing as it’s taught in British schools, the pressure to abandon school in London and move to Finland would be all but irresistible if they every got to hear the news.

With letter-forms that bear little resemblance to printed characters and a loopy style, apparently derived from old-fashioned copperplate, that few children are going to be able to master completely, let alone develop into an elegant mode of handwriting, joined-up handwriting remains for many an obstacle to, not a means of, communication.

Added to the benefits of Finnish schools my children already know about – the shorter working days, the lighter homework load, the absence of school uniforms, the good school meals, the outdoor breaks every hour – the news that not only will Finnish schoolchildren not be expected to develop good handwriting, but will be issued with tablets on which to practise their computer skills, would axe their enthusiasm for school at home in Britain.

For their mother, the puzzle remains how Finland manages to employ such child-friendly school policies and still remain close to the top of the global Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessments. The trick seems to be to recruit top-level graduates into well-run teacher training schemes, pay them well, and to trust them to do their job as teachers, without the mounds of paperwork and need for incessant testing that bedevil the job in Britain.

About the handwriting, my children will find out soon enough, when their friends in Finland come home carrying not exercise books but tablets.

But meanwhile, I’m keeping my fingers crossed they don’t see this piece.

Yikes! How good are Finnish schools now?

28 November 2013 | This 'n' that

Questions and answers. Illustration, from a Danish magazine, 1890: Wikimedia

The new PISA results were published in December: these tests, conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), measure the level of education of 15-year-old schoolchildren every three years.

Finland has done pretty well in recent years, so there has been interest in other countries in finding out what it is that makes Finnish schools better places for learning.

In 2000 Finnish pupils had been best at reading, and second at maths in 2003 – although competition has grown due to a larger number of countries, particularly in Asia – taking part in the study: for example, only 32 in 2000, but 65 in 2009 and in 2012.

In 2009 Finnish kids were third best in reading and sixth in maths. Now PISA 2012 results place Finnish kids in 12th place in maths, which created a stir in various educational circles. The best five were all Asian countries.

On the index list measuring skills at maths, science and literacy together, Shanghai leads, then come Singapore and Hong Kong. Finland is the best European country, number 7; Estonia is 8, Germany 16, Great Britain 21, the US 29, Sweden 38.

Non scholae, sed vitae discimus. Competition permeates everything now more than ever, but we do not learn for school but for life – not for PISA either. Still, teaching methods and students’ motivation are clearly worth improving.

The chances of learning on this globe are greater and more accessible than ever, but learning still takes brains, motivation and time. Yikes!

Good school, bad pupils, or vice versa?

21 December 2012 | This 'n' that

Number one: Finland. The Pearson analysis, 2012

Finland is used to feeling pretty good about itself when it comes to education. In the widely respected PISA tests – the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s exams in science and literacy – Finnish schoolchildren have, since the turn of the century, been outperforming most of their peers.

A shock came in 2009 when the tests revealed that Finnish kids were only third-best at reading, and sixth in maths; but by this time they were competing against the newly participating Asian countries, with their huge concentration on education.

Now, however, a new league table, drawn up by the education publishers Pearson, places Finland right at the top (2006–2010, 40 countries). Second place is held by South Korea; third is Hong Kong. The Pearson analysis uses a broader set of criteria, using not just test results but broader measures such as how many people go to university. In a result that is causing some puzzlement in the United Kingdom, Britain is rated sixth. Entirely, say critics, because British universities are so easy to get into.

The results are indeed flattering to Finland – but Finnish children’s motivation to learn is among the weakest in the survey’s countries. In reading, mathematics and the sciences Finns’ attitudes and application were low. It looks as if Finnish children consider school a place to hang out with their friends, not a place for teaching and learning. Countries where competition is stronger breed different attitudes.

So here’s the Finnish paradox: kids here hate school – yet still end up at the top of the list.

Must be something in the water.

In with the new?

17 December 2010 | Letter from the Editors

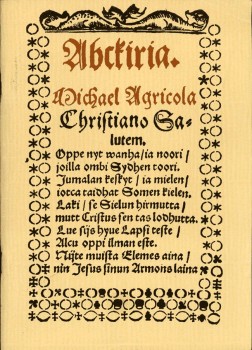

Abckiria (‘ABC book’, 1543): the first Finnish book, a primer by the Reformation bishop Mikael Agricola, pioneer of Finnish language and literature

In August 2010 the American Newsweek magazine declared Finland (out of a hundred countries) the best place to live, taking into account education, health, quality of life, economic dynamism and political environment.

Wow.

In the OECD’s exams in science and reading, known as PISA tests, Finnish schoolchildren scored high in 2006 – and as early as 2000 they had been best at reading, and second at maths in 2003.

Wow.

We Finns had hardly recovered from these highly gratifying pieces of intelligence when, this December, we got the news that in 2009 Finnish kids were just third best in reading and sixth in maths (although 65 countries took part in the study now, whereas in 2000 it had been just 32; the overall winner in 2009 was Shanghai, which was taking part for the first time.)

And what’s perhaps worse, since 2006 the number of weak readers had grown, and the number of excellent ones gone down. More…