Tag: classics

Poems

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

The poems of Aleksis Kivi were long considered no more than a peripheral aspect of his work. They were, as Kivi’s friend Kaarlo Bergbom wrote in a review, ‘gold that can’t be minted into coins’. The reason appears to have been Kivi’s poetic technique, which made a clear break with tradition. He did away almost completely with rhyme and instead emphasised the rhythm and musical sound qualities of words. He shortened words in a way that did not find favour with any subsequent Finnish poets. He avoided emotional expressions of patriotism and romantic love poetry; instead, he composed poems that were extended, narrative and fresco-like. Lauri Viljanen, whose 1953 study brought about a re-evaluation of Kivi’s poetry, has given them the apt soubriquet ‘epic idyll’.

The first of Kivi’s poems appeared in the Kirjallinen Kuukauslehti (‘Literary monthly magazine’) in 1866; a collection of his poetry entitled Kanervala was published the same year. Other poems appear in his novels and plays, and some have appeared in a collection after his death. Karhunpyynti (‘The bear hunt’) is from Kanervala. Its descriptive nature is typical of Kivi. The verse structure is tightly controlled but unrhyming. The winter landscape of the third verse, repeated at the end of the poem, is a ceremonious point of rest among the otherwise busy activity.

– Kai Laitinen

![]()

The Bear Hunt

The men on skis set out for the forest, a brave company

With guns and bright spears

And clamouring dogs on the leash,

With blazing eyes,

As the dawn chases gloomy Night

From the sky’s brow,

And the sun raises his head. More…

Poems

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Interview by Philip Binham

Birdmount

I hear a happy tale, it makes me sad:

no-one will remember me for long.

I will send a letter with nothing inside, the emptiness will reek

as the pines do, of fruit-peel and of smoke,

a scent only.

Here I have stayed a week, seven riverside days.

The river treads the mill, ah, treads the mill,

the river’s wide, this is a placid reach, the sky is near:

smoke, like the shadow of a birdflock passing, nothing else.

And now it is September:

there are more pine trees here, and more darkness too. More…

The power game

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

Mirdja

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Mirdja (1908). Introduction by Marja-Liisa Nevala

Now they were in the city – their minds more alive than usual with wilfulness and daring.

For – quite unable to jettison their shared life – they had at least to get on top it… Had to … Every single person has to battle …

And Mirdja’s head was full of efficacious rules for balance, countless cool and wise thoughts – to meet all conflicts.

Lucidly and coldly she had clarified her present position for herself. She was married. Right. No particular joy in that. But no need for any particular disaster in it either. And if she had thrown herself into dependence through this banal arrangement, the sort that everyone has a little of in this life, she had only herself to blame. She had to be able to live by rising above the trivialities of existence. Besides, she had always known that in the final count it was immaterial whom one was married to. A marriage always had its own profile, its dreary distinguishing marks, but one was not compelled to absorb these dreary sides into one’s own being. How did they do it in France? Every year thousands of marriages occur, without an atom of personal liking entering into the game, and extremely seldom are the marriages unhappy. Why so? Mutual politesse: a little of the art of social intercourse, and the whole problem is solved. In the morning a tiny friendly greeting at the breakfast table: ‘Bonjour ma chère,’ – ‘Bonjour, mon ami’; a courteous kiss on the hand, a pretty smile in response, and everything’s as it should be. Because those people know how to go about it. Marriage – one of society’s many empty regimentations! Only stupid people tried, within narrow limits like these, to find fullness of content or idealize. Stupid, Mirdja had been. Comically destructive in that heavy northern solemnity of hers – refusing to acknowledge any form without content, yet fearful of endowing content with any form except the conventional and time-tested. She had lived with a common-or-garden person’s longing for fullness, and then allowed, exactly like that sort of person, her disappointment and bitterness to flood over all her nearest and dearest. She had lived in indiscretion. She had been paltry and rotten and considered herself a slave … More…

Star-Eye

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

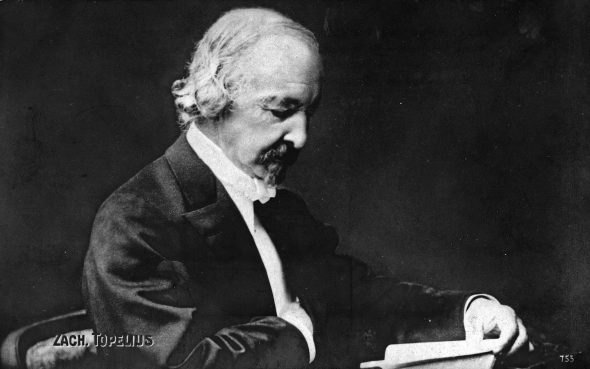

A story from Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’,1884). Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

There was once a little child lying in a snowdrift. Why? Because it had been lost.

It was Christmas Eve. The old Lapp was driving his sledge through the desolate mountains, and the old Lapp woman was following him. The snow sparkled, the Northern Lights were dancing, and the stars were shining brightly in the sky. The old Lapp thought this was a splendid journey and turned round to look for his wife who was alone in her little Lapp sledge, for the reindeer could not pull more than one person at a time. The woman was holding her little child in her arms. It was wrapped in a thick, soft reindeer skin, but it was difficult for the woman to drive a sledge properly with a child in her arms.

When they had reached the top of the mountain and were just starting off downhill, they came across a pack of wolves. It was a big pack, about forty or fifty of them, such as you often see in winter in Lapland when they are on the look-out for a reindeer. Now these wolves had not managed to catch any reindeer; they were howling with hunger and straight away began to pursue the old Lapp and his wife. More…

Howl came upon Mr Boo

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Drama, Fiction

The first Mr Boo book was published in 1973. Mr Boo has also made his appearance on stage this year; his theatrical companions are the children Mike and Jenny, who are not easily frightened – Mr Boo’s courage is a different matter, as can be seen in the extract from the stage play that follows overleaf.

Hannu Mäkelä describes the birth of Mr Boo:

To be honest, Mr Boo has long been my other self. The first time I drew a character who looked like him, without naming it Boo, I was really thinking of my fifteen year-old self.

The years went by and the Mr Boo drawing was forgotten for a time. It hadn’t occurred to me to write for children; I seemed to have enough to do coping with myself. Then I met Mr Boo, whom I had not yet linked up with my old drawing. My son was about six years old and we had been invited out. There were several children present. As I recall it it was a wet Sunday afternoon. I had entrenched myself with the other grown-ups in the kitchen to drink beer. The noise of the children grew worse and worse (in other words they were enjoying themselves). At last the women could bear it no longer and demanded that I, too, get to work. Really, what right had I always to be sprawled at a table with a beer glass in my hand? None. So I rose and went into the sitting-room. I shouted at the children to form a circle around me. At that time I had a motto: ‘Mäkelä – friend to children and dogs’. The reverse was true of course. The name Mr Boo occurred to me, probably as a result of some obscure private (and possibly even erotic) pun and I begun to tell a story about him. In telling it I paused dramatically and accelerated just as primary school teachers are taught to do: that part of my training, after all, wasn’t wasted. I was astonished; the children listened in complete silence. And if my memory doesn’t fail me (or even if it does, this is the way I wish to remember it), at the end of the story the smallest of the children said, rolling his r’s awkwardly, ‘Hurrrrah’. I was hooked.

The children themselves asked me to tell the same stories again. They still enjoyed them. It wasn’t long before I began to think seriously of writing a whole book about Mr Boo. For the first time in my life I really wanted to write for children. Every day after work I wrote a new Mr Boo story. Then in the evening I read it to my son. That is how the stories grew into a book.

The child likes right to triumph; he likes the good and the moral. The child is the kind of person we adults try in vain to be. It was only through Mr Boo that I began to see children in a totally new way and above all to become seriously interested in them.

Pekka the brave

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

An extract from Pekka Peloton (‘Pekka the brave’, 1982). Introduction by Leena Kirstinä

The other ghost was now very close to the Bear. The inhabitants of the Green Woods had pulled back out of its way in terror but the poor Bear couldn’t even get himself to budge. Miserable, he had covered his eyes and slumped down in his own fur.

‘Psst,’ the ghost whispered. ‘Hi, Bear, it’s only me.’ And the ghost poked the Bear in the ribs. ‘It’s me, Pekka. Come on, open your eyes!

But the Bear didn’t make a move to do what Pekka had asked and Pekka began to get worried. He knew the Wolf wouldn’t stay put for a very long time and little by little would start to wonder what this was all about. ‘Dear Bear,’ Pekka said in a louder voice, and punched him as hard as he could. ‘Get up! We haven’t much time … ‘ Pekka’s voice was trembling. ‘Look! I’ve got the key to your courage right here … ‘ More…