Tag: children’s books

Between covers

Issue 4/1990 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

Extracts from Lastenkirja (‘Children’s book’, WSOY, 1990, illustrated by the Estonian animator and graphic artist Priit Pärn)

CHILDREN’S BOOK IS BORN

Children are wafting around the world: they come spilling out of the chimneys and clattering out of the pipes. They worm around cramped places in the nether regions, rise up through stiff roots into the treetops and muss up the clouds. Children just happen anywhere and bring the Adults along with them. More…

‘ware bears!

Issue 3/1988 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

Illustration: Jukka Lemmetty

Urpo and Turpo are a pair of teddy bears. Their family – mother, father and three children – cannot imagine who it is that makes such a mess; the bears live their own absorbing lives in house. Hannele Huovi’s text and Jukka Lemmetty’s illustrations describe the bears’ antics in a way that appeals to the sense of humour of readers of all ages.

In the green house an ordinary family are living a perfectly ordinary life. There’s father, mother, The Big Daughter, The Son, and also The Baby as well. Mother keeps running back and forth all day long shouting, ‘Goodness gracious! Who’s responsible for this?’ For very funny things keep going on in the house. Who on earth is it – always getting up to some sort of hanky-panky?

Father harrumphs and says to The Big Daughter:

‘It was you, wasn’t it?’ But The Big Daughter shakes her head. Father turns to The Son:

‘So it must have been you, then?’ But the son shakes his head. No use asking The Baby. He shakes his head anyway, because he’s always imitating the others. Father and mother are completely stumped. More…

Star-Eye

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

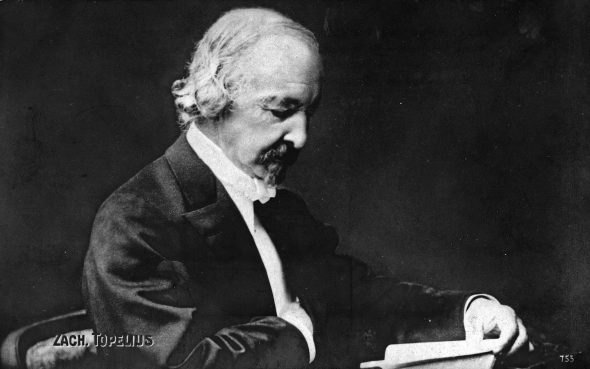

A story from Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’,1884). Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

There was once a little child lying in a snowdrift. Why? Because it had been lost.

It was Christmas Eve. The old Lapp was driving his sledge through the desolate mountains, and the old Lapp woman was following him. The snow sparkled, the Northern Lights were dancing, and the stars were shining brightly in the sky. The old Lapp thought this was a splendid journey and turned round to look for his wife who was alone in her little Lapp sledge, for the reindeer could not pull more than one person at a time. The woman was holding her little child in her arms. It was wrapped in a thick, soft reindeer skin, but it was difficult for the woman to drive a sledge properly with a child in her arms.

When they had reached the top of the mountain and were just starting off downhill, they came across a pack of wolves. It was a big pack, about forty or fifty of them, such as you often see in winter in Lapland when they are on the look-out for a reindeer. Now these wolves had not managed to catch any reindeer; they were howling with hunger and straight away began to pursue the old Lapp and his wife. More…

Howl came upon Mr Boo

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Drama, Fiction

The first Mr Boo book was published in 1973. Mr Boo has also made his appearance on stage this year; his theatrical companions are the children Mike and Jenny, who are not easily frightened – Mr Boo’s courage is a different matter, as can be seen in the extract from the stage play that follows overleaf.

Hannu Mäkelä describes the birth of Mr Boo:

To be honest, Mr Boo has long been my other self. The first time I drew a character who looked like him, without naming it Boo, I was really thinking of my fifteen year-old self.

The years went by and the Mr Boo drawing was forgotten for a time. It hadn’t occurred to me to write for children; I seemed to have enough to do coping with myself. Then I met Mr Boo, whom I had not yet linked up with my old drawing. My son was about six years old and we had been invited out. There were several children present. As I recall it it was a wet Sunday afternoon. I had entrenched myself with the other grown-ups in the kitchen to drink beer. The noise of the children grew worse and worse (in other words they were enjoying themselves). At last the women could bear it no longer and demanded that I, too, get to work. Really, what right had I always to be sprawled at a table with a beer glass in my hand? None. So I rose and went into the sitting-room. I shouted at the children to form a circle around me. At that time I had a motto: ‘Mäkelä – friend to children and dogs’. The reverse was true of course. The name Mr Boo occurred to me, probably as a result of some obscure private (and possibly even erotic) pun and I begun to tell a story about him. In telling it I paused dramatically and accelerated just as primary school teachers are taught to do: that part of my training, after all, wasn’t wasted. I was astonished; the children listened in complete silence. And if my memory doesn’t fail me (or even if it does, this is the way I wish to remember it), at the end of the story the smallest of the children said, rolling his r’s awkwardly, ‘Hurrrrah’. I was hooked.

The children themselves asked me to tell the same stories again. They still enjoyed them. It wasn’t long before I began to think seriously of writing a whole book about Mr Boo. For the first time in my life I really wanted to write for children. Every day after work I wrote a new Mr Boo story. Then in the evening I read it to my son. That is how the stories grew into a book.

The child likes right to triumph; he likes the good and the moral. The child is the kind of person we adults try in vain to be. It was only through Mr Boo that I began to see children in a totally new way and above all to become seriously interested in them.

Pekka the brave

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

An extract from Pekka Peloton (‘Pekka the brave’, 1982). Introduction by Leena Kirstinä

The other ghost was now very close to the Bear. The inhabitants of the Green Woods had pulled back out of its way in terror but the poor Bear couldn’t even get himself to budge. Miserable, he had covered his eyes and slumped down in his own fur.

‘Psst,’ the ghost whispered. ‘Hi, Bear, it’s only me.’ And the ghost poked the Bear in the ribs. ‘It’s me, Pekka. Come on, open your eyes!

But the Bear didn’t make a move to do what Pekka had asked and Pekka began to get worried. He knew the Wolf wouldn’t stay put for a very long time and little by little would start to wonder what this was all about. ‘Dear Bear,’ Pekka said in a louder voice, and punched him as hard as he could. ‘Get up! We haven’t much time … ‘ Pekka’s voice was trembling. ‘Look! I’ve got the key to your courage right here … ‘ More…