Search results for "Что такое нейролингвистическое воздействие больше в insta---batmanapollo"

Plain sailing

31 March 1996 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Alastalon salissa (‘In Alastalo’s parlour’, 1933). Introduction by Kai Laitinen

A letter from the translator:

Dear Editors,

Reluctantly (I really have tried) I have been driven to conclude that Alastalon salissa is untranslatable, except perhaps by a fanatical Volter Kilpi enthusiast who is prepared to devote a lifetime to it. To mention only one of the difficulties, there is no English equivalent to the style of the Finnish ‘proverbs’ (real or imaginary) with which the main character Alastalo’s thoughts are so thickly larded. Add to this the richness and, yes, eccentricity, of Kilpi’s vocabulary, and the unfamiliarity of much of the subject-matter, centred as it is on the interests of a sea going community that hardly exists any longer, even on the islands, and you have a text that is full of pitfalls for the translator. As for the humour, I’m sorry to say that it depends so much on the idiom and presentation that it doesn’t come over at all. If I did any more, I’m afraid it would just have to be a laborious paraphrase, and I don’t think I’m capable of making it effective, or even readable, in English.

Apart from that, although I’m very grateful for your explanations of the many unfamiliar words and phrases, I’m very unwilling to commit myself to the translation of any of them on the basis of a mere ‘gloss’ (technical word): I need to know the associations, and possible sound-echoes, of every one of them before I can be sure of getting it right. And getting it right affects the rhythm of every sentence: it’s not just a matter of filling in blanks with ‘equivalents’ provided by someone else.

I’ve no objection to your using my version of the opening pages. If you decide to follow it with some kind of comment, do borrow, if you need to, from my remarks above, giving the translator’s point of view. Sorry to have failed you so badly.

Yours, David Barrett More…

Positive fools

1 April 2010 | This 'n' that

‘People who think about what others think of them are above all afraid of being ridiculed. Consider it an irony of fate or not, but the Finns in literature are usually laughable in some way or other,’ Janna Kantola – lecturer in Comparative Literature in Helsinki University – writes in an article entitled ‘Strong, thirsty and weird’, published in the 6/2009 issue of the Helsinki University Bulletin.

Mostly they drink and end up on the wrong side of the law. For example, there are Finnish seafarers in fiction by European writers whose rum bottles apparently have no bottoms.

‘Finland and the Finns appear, in particular, in thrillers from the Cold War: from Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye (1953) to Alistair MacLean’s novel HMS Ulysses (1955). In these works, the unsmiling and hulking Finns have wide, horny hands, massive bottoms and the strength of a hundred men.

‘But not to worry. On a couple of occasions, Finns have even got to be the main characters of books. In these instances, the Finns no longer make people laugh but are mostly tragic, just as the characters in literature usually are when they are most interesting.

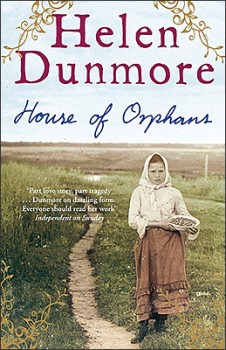

‘The main character in Richard Rayner’s novel The Cloud Sketcher (2000, USA) is an architect – a popular profession for Finns in modern literature – who has a disfigured face and a hard history, reaching America by way of the Finnish civil war. The historical novel by Helen Dunmore, House of Orphans (2006, UK), set in Finland in 1901–1904, is a love story about two young rebels, Eeva and Lauri.

One of the success stories of Finnish literature abroad are the humorous novels by Arto Paasilinna (born 1942): they have been translated into almost 40 languages. ‘Through his books Arto Paasilinna has turned being a fool into a positive characteristic. All things considered, this is something Finland will have no shortage in offering,’ Kantola concludes.

Irma-Riitta Järvinen: Kalevala Guide

10 September 2010 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Kalevala Guide

Kalevala Guide

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2010. 127 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-193-3

€ 24.90, paperback

This book is a brief but comprehensive English-language guide to the Finnish national epic, which was based on the archaic oral, sung folk poetry of Karelia, but collected and personally compiled by the scholar and writer Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884). The epic (first edition 1839, complemented in 1849) is set in a mythic past; technically speaking, the metre is an unrhymed, non-strophic trochaic tetrametre, characterised by alliteration. Contents, characters, places and themes are explained in the Guide, which also explores myths of origin and the significance of the epic. On his eleven trips to Archangel and North Karelia, Lönnrot met some 70 singers. The Kalevala, now translated, at least in part, into more than 60 languages, has inspired artists the world over (J.R.R. Tolkien was a fan, while Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Hiawatha imitates the metre and style of the Kalevala). The composer Jean Sibelius and the artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela are perhaps the best known Finnish Kalevala artists. And the inspiration continues: for instance, rock musicians and visual artists make use of Kalevala themes, stories and characters in their work. The book includes a list of relevant websites and a select bibliography.

Location, location, location

11 February 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

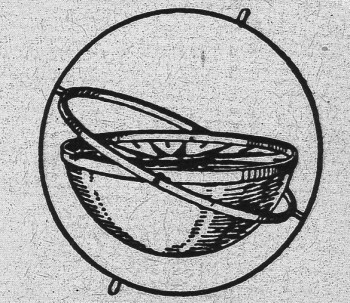

Before GPS: compass and and gimbal, 1570. Picture: Wikimedia

Art that requires navigation systems? Whatever next. In his column poet and writer Teemu Manninen wonders whether literature can function as ‘locative’. How to blend technology and art? Perhaps literature too might expand from the printed word

What if the Romantic poet John Keats had never published his poetry in print – if his works had been distributed only in manuscript form and read only by his friends and acquaintances? Had that been the case, the only way of hearing his poetry would have been at the salons and informal clubs that took place in literary people’s homes, at coffee houses, or other meeting places.

Keats might not even have, most likely, been in attendance himself, but maybe someone had a copy of a copy of a fragment of a poem that they might read to the gathered intellectuals and gentlefolk. You would have to have known the right people, have to have been at the right place at the right time to hear ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ read for the first and perhaps for the last time ever.

Or, what if Joyce had never intended for Ulysses to be published for the great reading public at all? What if, instead, he had left copies of each chapter around Dublin in the places where those chapters take place; what if, page by page, he had distributed his work in the actual locations of the events as they happened in his imagination? More…

Man and boy

31 December 2006 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kansallismaisema (‘National landscape’ Tammi, 2006). Introduction by Tuomas Juntunen

Plans were afoot to establish boys’ camps across the country. This was an experiment, a chance to test the water, to be a pioneer. Here was the opportunity to be the first in line to conquer the Wild West, just as many a brave cowboy had done in years gone by. The Ministry of General Affairs planned to put all 15-year-olds to work for the duration of the summer holidays. Casual labourers were often even younger. Our task was to ascertain a suitable minimum age. In addition, special camps were planned for those not suited to normal work camps. In the summers to come the youth of Finland would be fully employed. Weren’t we in fact driven by the same desire, Tikka had wondered. We both cared about the next generation. We wanted to root out their deficiencies so that they would be able to face life’s challenges to the full. More…

Finland, cool! The Frankfurt Book Fair 8–12 October

30 September 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

Finnland. Cool. pavilion in Frankfurt, designed by Natalia Baczynska Kimberley, Nina Kosonen and Matti Mikkilä from Aalto University

It starts next week: Finland is Guest of Honour at the Book Fair in the German and global city of Frankfurt. This link will take you to it all.

Approximately 170,000 professionals from the literary world are expected to visit the exhibition halls from Wednesday to Friday; the weekend is reserved for the general public, c.100,000 visitors. Since 1980s different countries have been in focus each year. More…

Punishment and delight

31 December 1995 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Pimeästä maasta (‘Out of the Land of Darkness’, Kirjayhtymä, 1995). Interview by Jukka Petäjä

‘A being far more powerful and wiser than ourselves made the mould at the beginning of time and set it up for us as a model in order that we might shape ourselves correctly,’ the teachers said. ‘The Prime Mover’s form, actions and thoughts we are unable to understand. The Prime Mover gave us the mould in order that we should not remain formless. To this extent it has made itself known to us, although we do not deserve anything from it. It did not make the mould of bog-iron, which would soon have rusted in the cellar, but of a much better material of which we know nothing, and need to know nothing. Our duty is to aspire to fill the perfect mould given to us perfectly. Most of us will never be able to do so, for we are worthless, formless, unclean messes who deserve, many times over, all the pain of fitting the mould.’

Ulthyraja Tharabereghist did not dare ask anything, but there was something she would have liked to know. How the Prime Mover had made the mould, at least, and where it had found the materials, and what the Mover had gone on to do and where it had gone when the mould was ready and in the possession of the villagers. Even illicit thoughts were said to damage one’s shape: to be visible in it, if one knew how to look, and, of course, to be felt in the pains of fitting the mould… More…

Animal crackers

30 June 2004 | Children's books, Fiction

Fables from the children’s book Gepardi katsoo peiliin (‘A cheetah looks into the mirror’, Tammi, 2003). Illustrations by Kirsi Neuvonen

Rhinoceros

The rhinoceros was late. She went blundering along a green tunnel she’d thrashed through the jungle. On her way, she plucked a leaf or two between her lips and could herself hear the thundering of her own feet. Snakes’ tails flashed away from the branches and apes bounded out of the rhino’s path, screaming. The rhino had booked an afternoon appointment and the sun had already passed the zenith.

The rhinoceros was late. She went blundering along a green tunnel she’d thrashed through the jungle. On her way, she plucked a leaf or two between her lips and could herself hear the thundering of her own feet. Snakes’ tails flashed away from the branches and apes bounded out of the rhino’s path, screaming. The rhino had booked an afternoon appointment and the sun had already passed the zenith.

When the rhinoceros finally arrived at the beautician’s, the cosmetologist had already prepared her mud bath. The rhino was able to throw herself straight in, and mud went splattering all round the wide hollow. More…

Reading matters? On new books for young readers

9 January 2014 | Articles, Children's books, Non-fiction

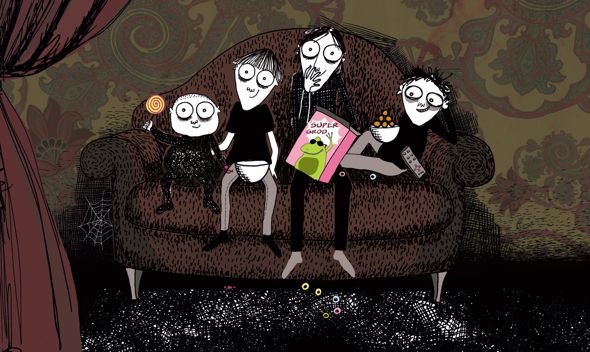

The Pixon brothers don’t read books, they love the telly: story by Malin Kivelä, illustrations by Linda Bondestam (Bröderna Pixon och TV:ns hemtrevliga sken, ‘The Pixon brothers and the homely shimmer of the telly’)

Finnish picture books for children have long been reliable export goods around the world. In the last few years, a number of novels for children have come along in their wake: works by authors such as Timo Parvela and Siri Kolu have been translated into a good many languages.

Now young adult literature has also blazed a trail on to the international market – in what also seems to be almost a matter of precision timing with regard to the Frankfurt Book Fair 2014. Finnish publishers have been investing in their home-grown lists of children’s and young adult books ever since the turn of the millennium, and now the time has come to harvest the fruits of their long-term efforts.

Chronicles of crisis

31 December 1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Books from Finland presents here an extract from Dyre prins, a novel by the Finland-Swedish writer Christer Kihlman that is to be published in 1983 by Peter Owen of London under the title Sweet Prince, in a translation by Joan Tate.

Christer Kihlman (born 1930) first became known as a poet; but, after publishing two collections of poetry, he turned to novels. He has been branded a merciless scourge of the bourgeoisie. Equally important in his writing, however, are his masterly psychological analyses, his examination of the myriad aspects of the human personality, his sovereign disregard for taboos and his unflagging search for the truth. His books are about crises – the conflict between the generations, between the individual and society, between opposing political ideologies, between homosexual and heterosexual love. As Ingmar Svedberg remarked in an extensive appreciation of Kihlman’s work that appeared in Books from Finland 1-2/1976, ‘In his perceptive moral analyses, his exploration of the depths of human destructiveness and degradation, Kihlman is sometimes reminiscent of Faulkner.’ Since 1970, Kihlman has published three revealing autobiographical works, two of them dealing with his encounter with South America; Dyre prins, first published in 1975, represents a brief interlude of fiction.

The extract printed below is accompanied with a personal appreciation of the novel by its English translator, Joan Tate

Grandfather’s astonishing revelation gave me a new perspective on my life. I had suddenly been given a concrete, genuine foundation for both my hatred and my self-esteem. In a way I took the story of my origins as an extreme confirmation of the rightness of the Communist interpretation of reality, and at the same time it gave me a wonderful, dazzling sensation of being someone, despite everything, of having a place in a meaningful human perspective of time, despite everything, of being a link, however modest, in the historical family tradition. I did not need to found a dynasty; I already belonged to a dynasty, if only a minor branch. One was less important than the other, and even if the two experiences were irreconcilable and contradictory, they existed all the same in the same consciousness, contained within the same consciousness, my consciousness. I, Donald Blad! More…

Six letters

31 March 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Tainaron (1985). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The whirr of the wheel

Letter II

I awoke in the night to sounds of rattling and tinkling from my kitchen alcove. Tainaron, as you probably know, lies within a volcanic zone. The experts say that we have now entered a period in which a great upheaval can be expected, one so devastating that it may destroy the city entirely.

But what of that? You need not imagine that it makes any difference to the Tainaronians’ way of living. The tremors during the night are forgotten, and in the dazzle of the morning, as I take my customary short cut across the market square, the open fruit-baskets glow with their honeyed haze, and the pavement underfoot is eternal again.

And in the evening I gaze at the huge Wheel of Earth, set on its hill and backed by thundercloud, with circumference, poles and axis pricked out in thousands of starry lights. The Wheel of Earth, the Wheel of Fortune… Sometimes its turning holds me fascinated, and even in my sleep I seem to hear the wheel’s unceasing hum, the voice of Tainaron itself. More…