Search results for "Что такое нейролингвистическое воздействие больше в insta---batmanapollo"

L’Amour à la Moulin Rouge

Extracts from the novella Yksin (‘Alone’, 1890). Introduction by Jyrki Nummi

After dining at the Duval on the Left Bank I take the same route back and drop in at the Café Régence to flick through the Finnish papers they have there.

I find my familiar café almost empty. The waiters are hanging about idly, and the billiard tables are quiet under their covers. The habitués are of course at home with their families. Anyone who has a friend or acquaintance is sharing their company this Christmas Eve. Only a few elderly gentlemen are seated there, reading papers and smoking pipes. Perhaps they’re foreigners, perhaps people for whom the café is their only home, as for me.

A little way off at the other end of the same table is a somewhat younger man. He was there when I came in. He’s finished his coffee and appears to be waiting. He’s restless and keeps consulting his watch. An agreed time has obviously passed. He calms himself and lights a cigarette. A moment later I can see a woman through the glass door. She’s hurrying across the street in front of a moving bus and running straight here. Now the man notices her too, and he cheers up and signals to the waiter for the bill. The woman slips through the door and goes straight across to him. They altercate for a moment, come to an understanding and depart hand in hand. More…

When sleeping dogs wake

31 December 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts rom the novel Tuomari Müller, hieno mies (‘Judge Müller, a fine man’, WSOY, 1994). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

In due course the door to the flat was opened, and a stoutish, quiet-looking woman admitted the three men, showed them where to hang their coats, indicated an open door straight ahead of them, and herself disappeared through another door.

After briefly elbowing each other in front of the mirror, the visitors took a deep breath and entered the room. The gardener was the last to go in. The home help, or whatever she was, brought in a pot of coffee and placed it on a tray, on which cups had already been set out, within reach of her mistress. The widow herself remained seated. They shook hands with her in tum. The mayor was greeted with a smile, but the bank manager and the gardener were not expected, and their presence came as a shock. She pulled herself together and invited the gentlemen to seat themselves, side by side, facing her across the table. They heard the front door slam shut: presumably the home help had gone out. More…

Hotel for the living

30 June 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…

In a class of their own

31 December 2006 | Children's books, Fiction

Extracts from the children’s book Ella: Varokaa lapsia! (‘Ella: Look out for children!’, Tammi, 2006). Interview by Anna-Leena Nissilä

There was a large van in the schoolyard with a thick cable winding its way from the van into the school. It was from the TV station, and the surprise was that they wanted to do a programme about our teacher, believe it or not.

The classroom was filled with lights, cameras, and adults.

‘Are you the weird teacher?’ a young man asked. He had a funny, shaggy beard and a t-shirt that said ‘errand boy’.

‘Not nearly as weird as your beard,’ our teacher answered.

‘Can we do a little piece about you?’ the errand boy asked.

‘Of course. A big one even. I’ve been expecting you, actually. Is it some educational programme?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘A substantive discussion programme, though?’

‘Not exactly.’

‘A documentary about our contemporary educators?’

‘Not quite.’ More…

The Conference

31 December 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Alamaisen kyyneleet (‘Tears of an underdog’, Karisto 1970). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Dr Smith said that he did not believe that any immediate threat of an invasion from Space was likely to arise for some time. Observations to date had given no support to the view that any such preparations had been put in hand. Technically they were of course ahead of us, but in his opinion there was no cause for panic. Nor could he endorse the widespread but naive assumption that any confrontation with beings from Space must inevitably lead to war. If human beings had reason to feel threatened, it was from each other that the chief threat came. He urged the Conference to work for a situation in which every country would be preparing for peace rather than for war. He said he had no wish to sound sardonic, but that he had noticed that when war was prepared for, it was usually war that ensued. More…

Manmother

31 December 2002 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Granaattiomena (‘Pomegranate’, WSOY, 2002). Introduction by Kristina Carlson

The journey

Mother had sent her son to the island of Rome.

She’d sent him for pleasure and recreation, and also to have a little time by herself. Even though their life together was on an even keel, it was sensible to have some time away from each other. She herself was sixty-eight, and her son an unmarried hermit in his thirties, on sickness allowance for the last couple of years. He was afflicted with chronic depression. The doctors had been unable to identify the cause. The origin of a disorder of that sort was often looked for in some infant trauma; but the boy’s childhood, from all appearances, had been harmonious. One doctor suspected the time of his father’s terminal illness, when the boy had had to nurse his father for a long while. More…

Onward, downward!

31 March 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Lauri Viita (1916–1965) was one of the self-taught writers who made his debut after the Second World War. His extensive, realist novel Moreeni (‘Moraine’, 1950) taking place in Viita’s native Tampere, begins with this prose poem

…over wolds, hummocks, ridges, between boulders, under branches, from cabin to cottage to manor, from coppice to fen, and ditch to puddle – down it drew us, the sloping earthcrust, southward the magnificent granite ploughland slanted.

Paths linked to paths, brooks joined brooks. Onward, downward! The roads widened, the currents strengthened. Bigger and bigger, heavier and heavier were the loads they could sustain. More and more trees, bread, potatoes, butter, meat, people and gravestones, huge boulders, rocks, went into the maw of those channels, and the hunger only redoubled. From channel to strait, from hour to hour, the lines of barges crawled along; from day to day the broad rafts of logs passed their sleepless summer on the long blue strip of Lake Näsijärvi. Spruce, pine, birch, aspen – different pieces for different purposes. How vast the supply and how vast the need! The months and days went by; in the depths of the lake, layer after layer, there wandered the shades of clouds, ships, faces. More…

Breton without tears

31 March 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Euroopan reuna (‘The edge of Europe’, Otava, 1982). Introduction by H. K. Riikonen

I am reading a book, it says pour l’homme latin ou grec, un forme correspond à un être; pour le Celte, tout est metamorphose, un même individu peut prendre des apparences diverses, so it says in the book. A strange claim, considering that the word metamorphosis is Greek, and that the best-known book about metamorphoses, Ovid’s Metamorphoseon libri XV was written in Latin. In the myths of all peoples, at least the ones whose oral poetry was recorded in time, such as the Greeks, Serbs, Slavs, Finns, or Aztecs, metamorphoses play a very important part, the Celts are not an exceptional tribe in this respect. The author must mean that the Celts still live in mythical time, the time of metamorphoses when the human being assumed shapes, was able to fly as a bird, swim as a fish, howl as a wolf, and to crown his career by rising up into the sky as a constellation. Brittany is part of the Armorica Joyce tells us about in Finnegans Wake, that book is incomprehensible if one does not know Ireland, and now I see that Brittany is the key to one of the book’s locked rooms. I thought I already had keys to all the rooms after Dublin, the Vatican, and Athens, but one door was and remained closed, the key is here now, in my hand, I can get into all the rooms in the book, and I am home even if I should happen to get lost. The room creates the person, she becomes another when she goes from one room to another, this is metamorphosis, and when she leaves the house she disappears, she no longer exists. The legend on the temple at Delphi, gnothi seauton, know thyself, has led Occidentals onto the false track that is now becoming a dead end, polytheistic religions correspond to the order of nature, but as soon as the human starts to imagine that she knows herself, as soon as the metamorphic era ends, monotheism is born, the human being creates god in her own image, and that is the source of all evil. Planted like traffic signs at the far end of this cul-de-sac stand the hitlers and brezhnevs and reagans and thatchers, new leaves are appearing on the trees, the sun is shining. Landet som icke är* är en paradox: landet blev befintligt därigenom att Edith Södergran sade att det icke är. On the sea sailed a silent ship*, as I tracked my shoeprints across the sand on the beach, it was like walking on a street made out of salty raw sugar, I felt desolate. The wind bent the grasses, the sun warmed the back of my sweater, of course the sun always has the last word, I thought, things should be as they are, this thought gave me peace of mind. I walked past the cows, two of them already chewing the cud, the others still grazing, they stood in a line and raised their heads, stood at attention, as it were, as I walked past. I was not entirely sure that I was heading in the right direction, but then I saw the boucherie and knew that there was a café nearby. Madame greeted me in a friendly fashion, brought me a calvados and a beer and sat down for a chat, wanted to know if I liked the countryside here. I said that things looked the same here as in Ireland, she said that was true, but she had never been to Ireland. I finished my drinks and paid, left, decided to walk along the beach. I saw gun emplacements and two bunkers. I crawled into a bunker. Inside, it was dark and damp. I looked through the embrasure at the sea. I thought of the boys who had been incarcerated here. They had been given a death sentence. I examined a rusty object, what was it, I looked at it more closely, it was an axle from a gun’s undercarriage. As I arrive in my home yard, I note that the lilacs are beginning to bloom. More…

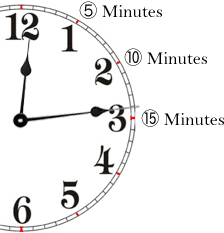

In your own time

16 March 2010 | This 'n' that

Ever wished there were just a few more hours in the day? We certainly have. Forgive us if you’ve seen it before, but this little homily has been doing the rounds on the internet in Finland. It made us laugh, if a little hollowly.

Ever wished there were just a few more hours in the day? We certainly have. Forgive us if you’ve seen it before, but this little homily has been doing the rounds on the internet in Finland. It made us laugh, if a little hollowly.

It’s healthy to eat an apple a day, and a banana, for the calcium, and an orange, for the vitamin C, and you need to drink a cup of green tea to reduce your cholesterol. You should also drink two litres of water (and wee the same amount, which doubles the amount of time you spend in the bathroom). And don’t forget the two decilitres of yogurt that you should eat to keep the bacterial flora of your stomach healthy. No one really knows what these bacteria are, but you MUST have at least a million of them, or you won’t be well! You must also drink a glass of red wine a day so you don’t have a heart attack, and a glass of white wine to protect your nervous system! And a glass of beer (I can’t quite remember why), but if you drink them all at the same time you may have a stroke. That won’t matter, though, as you won’t notice it. Everyone should also eat nuts and beans/peas every day. You should eat 4-6 times a day, light meals, but don’t forget that each mouthful should be chewed at least 36 times. That will take up 5 hours of your day! More…