Search results for "mauri kunnas"

Suburban dreams

30 March 2004 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Kahden ja yhden yön tarinoita (‘Tales from two and one nights’, Sammakko, 2003)

Reponen, Tane, Aleksi and Little Juha; once we all climbed up the path to the old dump with bows on our backs, our arrows sticking out from the tops of our boots. It was April. In the field above the dump puddles reflected the opaque sky, where we were going to shoot our arrows.

The field was the highest point in our neighbourhood. We could see the shopping centre, the library and the sawdust running track through the school woods. We could see the high-rise flats on Tora-alhontie road and the huts in the allotments. We could make out the thick spruce forest of Sovinnonvuori along the greenish grey coastline at Kapeasalmi. Our homes sat there below us. Softly droning cranes, yellow totem animals of hope, swung back and forth above the unfinished houses. In the distance was the centre of town with all its churches and scars. Here everything was just beginning. The swaggering confidence of ten-year-old boys was straining within us and would carry us far like Geronimo’s bow. More…

Hannele Huovi: Karvakorvan runopurkki [Furry pooch’s jar of verse]

4 March 2009 | Mini reviews

Karvakorvan runopurkki

Karvakorvan runopurkki

[Furry pooch’s jar of verse]

Kuvitus [Ill. by]: Kristiina Louhi

Helsinki: Tammi, 2008. 79 p.

ISBN 978-951-31-3974-2

€ 23.30, hardback

‘Methinks,/ said the sausage dog / who loved eating verse, that / poetry is tastier than bone’. Hannele Huovi (born 1949) has written poetry, books for children, novels and fables. The masterly rhymes of Finland’s grand old lady of children’s poetry, Kirsi Kunnas (born 1924), are hard to match, but Huovi comes close. For her, Finnish is easily pliable; her rhymes do not try to be too clever, her tone of voice is warm and humorous, and often the poems are little stories in the tradition of nonsense verse. Huovi’s sense of humour matches perfectly with Kristiina Louhi’s pastel pictures which often add surprising dimensions to the poetic stories. ‘So complete / trust can be: / with your paws skywards, /with your belly bared, you can / lie in the grass.’

In memoriam Herbert Lomas 1924–2011

23 September 2011 | In the news

Herbert Lomas. Photo: Soila Lehtonen

Herbert Lomas, English poet, literary critic and translator of Finnish literature, died on 9 September, aged 87.

Born in the Yorkshire village of Todmorden, Bertie lived for the past thirty years in the small town of Aldeburgh by the North Sea in Suffolk. (Read an interview with him in Books from Finland, November 2009.)

After serving two years in India during the war, Bertie taught English first in Greece, then in Finland, where he settled for 13 years. His translations – as well as many by his American-born wife Mary Lomas (died 1986) – were published from as early as 1976 in Books from Finland.

Bertie’s first collection of poetry (of a total of ten) appeared in 1969. His Letters in the Dark (1986) was an Observer book of the year, and he was the recipient of several literary prizes. His collected poems, A Casual Knack of Living, appeared in 2009.

In England Bertie won the Poetry Society’s 1991 biennial translation award for one of his anthologies, Contemporary Finnish Poetry. The Finnish government recognised his work in making Finnish literature better known when it made him a Knight First Class of Order of the White Rose of Finland in 1987.

To Books from Finland, he made an invaluable contribution over almost 35 years – an incredibly long time in the existence of a small literary magazine. The number of Finnish authors and poets whose work he made available in English is countless: classics, young writers, novelists, poets, dramatists.

Bertie’s speciality was ‘difficult’ poets, whose challenge lay in their use of end-rhymes, special vocabulary, rhythm or metre. He loved music, so the sounds and tones of words, their musicality, were among the things that fascinated him. Kirsi Kunnas’ hilarious, limerick-inspired children’s rhymes were among his best translations – although actually nothing in them would make the reader think that the originals might not have been written in English. A sample: There once was a crane / whose life was led / as a uniped. / It dangled its head / and from time to time said:/ It would be a pain / if I looked like a crane. (From Tiitiäisen satupuu, ‘Tittytumpkin’s fairy tree’, 1956, published in Books from Finland 1/1979.)

Bertie also translated work by Eeva-Liisa Manner, Paavo Haavikko, Mirkka Rekola, Pentti Holappa, Ilpo Tiihonen, Aaro Hellaakoski and Juhani Aho among many, many others; for example, the prolific writer Arto Paasilinna’s best-known novel, Jäniksen vuosi / The Year of the Hare, appeared in his translation in 1995. Johanna Sinisalo’s unusually (in the Finnish context) non-realist troll novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi / Not Before Sundown, subsequently translated into many other languages, appeared in 2003. His last translation for Books from Finland was of new poems by Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen in 2009.

It was always fun to talk with Bertie about translations, language(s), writers, books, and life in general. He himself said he was a schoolboy at heart – which is easy to believe. He was funny, witty, inventive, impulsive, sometimes impatient – and thoroughly trustworthy: he just knew how to find the precise word, tone of voice, figure of speech. He had perfect poetic pitch. As dedicated and incredibly versatile translators are really hard to find anywhere, we all realise our good fortune – both for Finnish literature and for ourselves – to have worked, and enjoyed with such enjoyment, with Bertie.

Poet Aaro Hellaakoski (1893–1956) was not a self-avowed follower of Zen, but his last poems, in particular, show surprisingly close contacts with the philosophy. ‘Secrets of existence are revealed once one ceases seeking them’, the literary scholar Tero Tähtinen wrote in an essay published alongside Bertie’s new Hellaakoski translations in (the printed) Books from Finland (2/2007). Bertie was fond of Hellaakoski, whose existential verses fascinated him; among his 2007 translations is The new song (from Vartiossa, ‘On guard’, 1941):

The new song |

Uusi laulu |

| No compulsion, not a sting. | Ei mitään pakota, ei polta. |

| My body doesn’t seem to be. | On ruumis niinkuin ei oisikaan. |

| As if a nightbird started to sing | Kuin alkais kaukovainioilta |

| its far shy carol from some tree – | yölintu arka lauluaan |

| as if from its dim chrysalis | kuin hyönteistoukka heräämässä |

| a little grub awoke to bliss – | ois kotelossaan himmeässä |

| or someone struck from off his shoulder | kuin hartioiltaan joku loisi |

| a miserable old bugaboo – | pois köyhän muodon entisen |

| and a weird flying creature | ja outo lentäväinen oisi |

| stretched a fragile wing and flew. | ja nostais siiven kevyen. |

| Ah limitless bright light: | Oi kimmellystä ilman pielen. |

| the gift of lyrical flight! | Oi rikkautta laulun kielen. |

More Tumpkin tales

30 June 1992 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Tiitiäisen pippurimylly (‘The Tumpkin’s pepper mill’, Otava, 1991). Kirsi Kunnas’s classic children’s books, Tiitiäisen satupuu (‘The Tumpkin’s story tree’) and Tiitiäisen tarinoita (‘The Tumpkin’s tales’), appeared in 1956 and 1957

Mr Saxophone and Miss Clarinet

Mr Saxophone went moony beginning to fret about Miss Clarinet: Moan moan moan darling little crow! I love you so! moaned Mr Saxophone.

Miss Clarinet was very upset: I won't be owned! And I'm no little crow! I sob like a dove, and even about love I sing alone! Oh moan moan moan groaned Mr Saxophone.

Poems

30 June 1979 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction, poetry

Kirsi Kunnas. Photo: Jyrki Luukkonen

Poems from Tiitiäisen satupuu (‘The Tittytumpkin’s fairy tree’, 1956)

The old water rat

There’s a shiver of a reed,

a rustle in the grass,

a slop-slopping through the mud:

Who’s that puffing past?

Who’s that peeping there?

A whiskery head

and a muddy tread.

It’s Old Mattie

Water Rattie.

Squeezing water from his eyes,

trickling from his sneezing nose,

freezing and sneezing.

Then: Oh dear Misery!

A-snee, a-snee, a-snizzery! More…

A thankless task?

24 November 2011 | Letter from the Editors

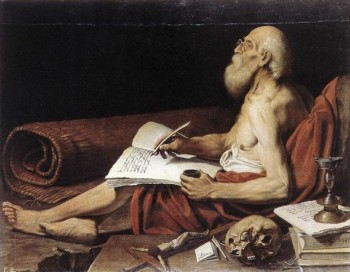

Translator at work: St Jerome, translator of the Latin Bible in the late 4th century, is the patron saint of translators and librarians. Leonello Spada's 1610s painting, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome. Picture: Wikimedia

Why translate, asked the late Herbert Lomas thirty years ago in an issue of Books from Finland (1/82) – the pay’s absurd, one’s own writing suffers from lack of time, it’s very hard to please people. And public demand for translation from minor languages into English was almost non-existent.

But he also admitted that translating is generally a pleasurable experience: ‘You have the pleasure of writing without the agony of primary invention. It’s like reading, only more so. It’s like writing, only less so.’ More…

Coming up next week…

7 May 2010 | This 'n' that

‘…A strange tapir / (the bi-coloured one) / a wondrous tapir (the many-toed one) / circles the tree, goes round and about, / a small word hangs from the tip of his snout….’

Helvi Juvonen (1919–1959) wrote nature-inspired poetry; she was a fan of the 19th-century American poet Emily Dickinson, whose work she also translated. Her short adult life, in the drab Helsinki of the post-war years, was burdened by poverty and illness, and yet she wished to ‘toast the richness of our lives’.

The literary scholar Emily Jeremiah has translated a handful of Juvonen’s poems and takes a look at her work in this, the 15th part of a series devoted to classic Finnish authors (also available in our archive are essays about Kirsi Kunnas, Henry Parland and Sirkka Turkka). Helvi Juvonen: small words celebrate ‘the richness of our lives’

Who for? On new books for children and young people

29 January 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

Books have a tough time in their struggle for the souls of the young: more titles for children and young adults than ever before are published in Finland, all of them trying to find their readers. Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen picks out some of the best and most innovative reading from among last year’s titles

Nine-year-old Lauha’s only friend and confidant is her teddy bear Muro, because Lauha is an outsider both at home and at school. The children’s novel Minä ja Muro (‘Muro and me’, Otava), which won the 2009 Finlandia Junior Prize, provoked discussion of whether it was appropriate for children, with its oppressive mood and the lack of any bright side brought into the life of the main character in its resolution. More…