Search results for "david barrett"

The nursemaid

Lapsenpiika (‘The nursemaid’), a short story, first published in the newspaper Keski-Suomi in December, 1887. Minna Canth and a new biography introduced by Mervi Kantokorpi

‘Emmi, hey, get up, don’t you hear the bell, the lady wants you! Emmi! Bless the girl, will nothing wake her? Emmi, Emmi!’

At last, Silja got her to show some signs of life. Emmi sat up, mumbled something, and rubbed her eyes. She still felt dreadfully sleepy.

‘What time is it?’

‘Getting on for five.’

Five? She had had three hours in bed. It had been half-past one before she finished the washing-up: there had been visitors that evening, as usual, and for two nights before that she had had to stay up because of the child; the lady had gone off to a wedding, and baby Lilli had refused to content herself with her sugar-dummy. Was it any wonder that Emmi wanted to sleep? More…

The Conference

31 December 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Alamaisen kyyneleet (‘Tears of an underdog’, Karisto 1970). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Dr Smith said that he did not believe that any immediate threat of an invasion from Space was likely to arise for some time. Observations to date had given no support to the view that any such preparations had been put in hand. Technically they were of course ahead of us, but in his opinion there was no cause for panic. Nor could he endorse the widespread but naive assumption that any confrontation with beings from Space must inevitably lead to war. If human beings had reason to feel threatened, it was from each other that the chief threat came. He urged the Conference to work for a situation in which every country would be preparing for peace rather than for war. He said he had no wish to sound sardonic, but that he had noticed that when war was prepared for, it was usually war that ensued. More…

The lake

30 June 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Järvi (‘The lake’), a short story, 1915. Introductions by Kai Laitinen and Pekka Tarkka

I travel the world, not out of any desire for adventure, but because that is the way things have happened. The best of my wanderings are in obscure, tucked-away regions, where life is humdrum and pitched in a low key. There I have no need to stave off nostalgia for the past by leading a hectic life: my days go by in stolid succession from season to season, I am an ordinary unimportant individual among all the rest. For long stretches of time my life does not strike me as being either dull or bright; I derive a certain satisfaction from its very emptiness. It is as though I were, by degrees and to the best of my ability, paying off a kind of debt. More…

Aphorisms

31 December 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Aphorisms from Pahojen henkien historia (‘A history of evil spirits’, 1986). Markku Envall’s essay on aphorism

Do not set out in the wrong mood, at the wrong moment, for the wrong place.

Learn to distinguish these from one another, for it is an impossible task.

Do not admit to changes in yourself, say rather that your associates vary.

And that your relationships are changeable. But do not say this of yourself.

Not knowing a person should not be regarded as sufficient reason for not making his acquaintance. More…

Poems

30 September 1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

The poems of Aleksis Kivi were long considered no more than a peripheral aspect of his work. They were, as Kivi’s friend Kaarlo Bergbom wrote in a review, ‘gold that can’t be minted into coins’. The reason appears to have been Kivi’s poetic technique, which made a clear break with tradition. He did away almost completely with rhyme and instead emphasised the rhythm and musical sound qualities of words. He shortened words in a way that did not find favour with any subsequent Finnish poets. He avoided emotional expressions of patriotism and romantic love poetry; instead, he composed poems that were extended, narrative and fresco-like. Lauri Viljanen, whose 1953 study brought about a re-evaluation of Kivi’s poetry, has given them the apt soubriquet ‘epic idyll’.

The first of Kivi’s poems appeared in the Kirjallinen Kuukauslehti (‘Literary monthly magazine’) in 1866; a collection of his poetry entitled Kanervala was published the same year. Other poems appear in his novels and plays, and some have appeared in a collection after his death. Karhunpyynti (‘The bear hunt’) is from Kanervala. Its descriptive nature is typical of Kivi. The verse structure is tightly controlled but unrhyming. The winter landscape of the third verse, repeated at the end of the poem, is a ceremonious point of rest among the otherwise busy activity.

– Kai Laitinen

![]()

The Bear Hunt

The men on skis set out for the forest, a brave company

With guns and bright spears

And clamouring dogs on the leash,

With blazing eyes,

As the dawn chases gloomy Night

From the sky’s brow,

And the sun raises his head. More…

A Wedding Dance

31 March 1977 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Kivenpyörittäjän kylä (‘The stoneroller’s village’). Introduction by Hannes Sihvo

Pölönen got up and went over to his accordion, which he had dumped beside the juke-box. He walked with his stocky trunk thrust forward, his hands dangling; the wallet he had crammed into his hip-pocket, constrained to follow the curve of his fat buttock, made an unsightly bulge suggestive of some kind of excrescence. With a vigorous shoulder movement he hoisted the instrument into position. At once the neck of the bottle in his inside pocket came into view, emitting spurts of foam, and it was some time before he noticed it and managed to nudge it back so that it would lean the other way. Scarlet in the face and streaming with sweat, glaring angrily and doing his utmost to avoid looking in the direction of the assembled company, Pölönen drew some air into the bellows and tried out various notes and chords, fingering the keyboard with an airy nonchalance intended to suggest that he was a complete master of his instrument. All eyes were turned upon this podgy, fair-haired man, with the suit that was far too tight across the shoulders and under the armpits, the very small and rather crumpled tie, the tapering trouser legs with shiny bulges at the knees. The warming-up process continued for what seemed an unconscionably long time, and a certain amount of shuffling and coughing began to be audible; old Nestori Pölönen gazed stiffly down at his shoes, and Saara’s movements, as she busied herself behind the coffee-table, became more and more fidgety. More…

The strike

13 December 1980 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Täällä Pohjantähden alla (‘Here beneath the North Star’), chapter 3, volume II. Introduction by Juhani Niemi

With banners held aloft, the procession of strikers moved towards the Manor. It was known that the strikebreakers had arrived early and that the district constable was with them. Just before reaching the field the marchers struck up a song, and they went on singing after they had halted at the edge of the field. The men at work in the field went on with their tasks, casting occasional furtive glances at the strikers. Nearest to the road stood the Baron and the constable. Uolevi Yllö’s head was bandaged: someone had attacked him with a bicycle chain as he left the field at dusk the evening before. Arvo Töyry was in the field too, the landowners having agreed that those who had got their own harrowing and sowing done should lend the others a hand. Not all the men in the field were known to the strikers. The son of the district doctor was there they noticed, and the sons of several of the village gentry, as well as the men from the smallholdings. More…

The Onlookers

30 September 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Naisten vuonna (‘In women’s year’, 1975). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

The two elks came out on to the road through a gap between timber sheds. They began to cross the road, and the larger one was very nearly run into by a car. Cars stopped and horns tooted, till the elks turned and made off towards the harbour. Several cars swung round and drove along the cinder track in pursuit of the animals.

The elks headed across the rubble towards the power station; after circling some stacks of railway sleepers, they ended up on the flank of a coalheap sixty feet high. The cars pulled up and their occupants poured out, shouting that the elks wouldn’t go that way, it was a dead end. The elder of the two elks had indeed sensed this, and they moved off to the right, skirting the coal-heap and emerging among the timber-stacks. By this time the first cyclists and pedestrians had arrived on the scene.

“They’ll break their legs,” said a pedestrian to a motorist. “There’s all kinds of junk lying about.” More…

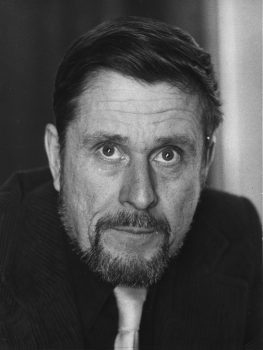

Human Freedom

30 June 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Mika Waltari. Photo: SKS Archives

Extract from lhmisen vapaus (‘Human Freedom’, 1950)

‘Where are we?’ Yvonne asked. ‘This isn’t the right street either. Somewhere between Alma and Georges V, they said. But there’s no sign of an aquarium.’

‘Talking of aquariums’, I suggested, ‘there’s a dog shop near here where they wash dogs in the back room. If you like, I’ll take you to see how they wash a dog. It’s a very soothing experience.’

‘You’re crazy’, said Yvonne.

My feelings were hurt. ‘I may sleep badly’, I admitted, ‘but I love you. I walk up and down the embankments all night. My heart aches, my brain is on fire. Then comes blissful intoxication, and for a little while I can be happy. And all you can do is to keep nagging, Gertrude.’

She wrinkled her brow, but I went on impatiently, ‘Look, Rose dear, just at present I have the whole world throbbing in my temples and in my finger-tips. Age-old poems are bubbling up within me. I am grieving for lost youth. I am boggling at the future. For just this one moment it is given to me to see life with the living eyes of a real human being. Why won’t you let me be happy?’

‘I have walked two hundred kilometres’, said a low, timid voice at my elbow. I stopped. Yvonne had stuck her arm through mine. She, too, stopped. We both looked down and saw a little man. He doffed a ragged cap and bowed. Flushed scars glowed through a grey stubble of beard. He was wearing a much-patched battle-dress from which the badges had long since disappeared. His face was wrinkled, but the little eyes were animated and sorrowful. More…

Sensitivity session

30 June 1978 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Ja pesäpuu itki (‘And the nesting-tree wept’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

Taito Suutarinen knew quite a bit about Freud. Where Mannerheim’s statue now stands, Taito felt that there ought instead to be an equestrian statue of Sigmund Freud. It would be like truth revealed.

Freud, urging on his trusty stallion Libido, would be clad from head to foot in sexual symbols – hat, trousers, shoes: one hand thrust deep into his pocket, the other grasping a walking-stick. The stick would point eloquently in the direction of the railway tracks, where the red trains slid into the arching womb of the station.

Taito had also attended a couple of seven-day sensitivity training courses, where people expressed their feelings openly, directly and spontaneously. By the end of the first course Taito was so direct and spontaneous that he couldn’t get on with anybody. By the end of the second he was so open that everyone was embarrassed. Every member of the group had cried at least once, except the group leader. Never before had Taito witnessed such power. He could not wait to found a group of his own. Taito’s group met in a basement room, where they reclined on mattresses to assist the liberation process. Everyone was free to have problems, quite openly. You were not regarded as ill: on the contrary, if you realized your problem you were more healthy than a person who still thought he mattered. Moreover, as Taito, fixing you with his piercing gaze, was always careful to emphasize, every problem was ultimately a sexual problem. Taito would spontaneously scratch his crotch as he spoke, making it clear that he himself had virtually no problems left. More…

A day in the life of a bookseller

12 August 2010 | Reviews

The bookseller Aapeli [Abel] Muttinen, a central figure in Joel Lehtonen’s ‘Putkinotko’ books, is one of those fictional characters for whom Finnish readers have cherished a particular affection, not least because of his keen enjoyment of the pleasures they themselves so regularly share when they escape to their lakeside cottages for the summer.

But although Aapeli Muttinen is Finnish through and through, he is not without counterparts in the literature of other nations. One of his close relatives is the laziest man in all literature, Goncharov’s Oblomov; others, perhaps more surprisingly, can be found in the works of Anatole France – booksellers like Blaizot and Paillot, both gentle dilettanti with a streak of individualism and a penchant for good living. Like them, Muttinen is tolerably well-read: at the beginning of the short story ‘A happy day’ we find him musing about Horace, and at least one of Horace’s odes must have appealed to him strongly: ‘Happiest is he who, like his sires of old, / Tills his own ground, and lives his life in peace, / Far from the tumult of the noisy world.’

More…

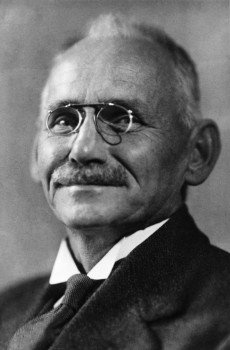

Kullervo: to be, or not?

10 September 2010 | Articles, Non-fiction

A young man is born a slave under stars that augur ill for him. He is maltreated and betrayed from birth. He cannot control his physical power, his aggression or his thirst for revenge and, finally, after fatal errors and deliberate acts of violence, his remaining desire is to die. What, in the end, did life hold for him?

The cruelly tragic story of Kullervo in the Kalevala was largely the creation of the national epic’s compiler, Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884), who put together a number of originally unconnected folk-epic fragments collected in disparate localities throughout the north and east of Finland. This process involved many stages and went on for decades. The first version was published in 1835; for a shorter version for schools in 1862 Lönnrot cut the most violent and erotic scenes – including those involving Kullervo and his sister in an incestuous encounter. More…

Six letters

31 March 1986 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

From Tainaron (1985). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

The whirr of the wheel

Letter II

I awoke in the night to sounds of rattling and tinkling from my kitchen alcove. Tainaron, as you probably know, lies within a volcanic zone. The experts say that we have now entered a period in which a great upheaval can be expected, one so devastating that it may destroy the city entirely.

But what of that? You need not imagine that it makes any difference to the Tainaronians’ way of living. The tremors during the night are forgotten, and in the dazzle of the morning, as I take my customary short cut across the market square, the open fruit-baskets glow with their honeyed haze, and the pavement underfoot is eternal again.

And in the evening I gaze at the huge Wheel of Earth, set on its hill and backed by thundercloud, with circumference, poles and axis pricked out in thousands of starry lights. The Wheel of Earth, the Wheel of Fortune… Sometimes its turning holds me fascinated, and even in my sleep I seem to hear the wheel’s unceasing hum, the voice of Tainaron itself. More…

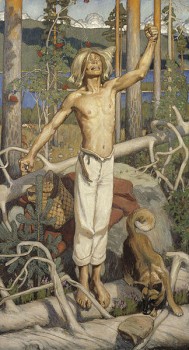

Kullervo

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

An extract from the tragedy Kullervo (1864). Introduction by David Barrett

The plot of the Kullervo story as told in the Kalevala: Untamo defeats his brother Kalervo’s army, and Kalervo’s son Kullervo is born a slave. Untamo sells him as a young child to llmarinen whose wife, the Daughter of Pohjola, makes the boy a shepherd and bakes him a loaf with a stone inside it. Kullervo takes his revenge by sending home a flock of wild animals, instead of cattle, who tear her to pieces. He flees, and discovers that his parents and two sisters are alive on the borders of Lapland. He finds them, but one of his sisters is lost. Life in the family home is unhappy: Kullervo fails in all the tasks his father sets him. On his way home one day he finds a girl in the forest whom he abducts in his sledge and seduces. It turns out the girl is his lost sister, who drowns herself when she learns that Kullervo is her brother. Kullervo sets out to revenge himself on Untamo; he kills and destroys. When he returns home, he finds the house empty and deserted, goes into the forest and falls on his sword.

ACT II, Scene 3

Kalervo’s cottage by Kalalampi Lake. It is night-time. Kimmo, seated by a fire of woodchips, is mending nets. More…