Search results for "Aseguranzas para autos Pompano Beach FL llama ahora al 888-430-8975 Calcular valor de seguro automotor Buscador seguros auto La caja de seguros automotor Asegurar mi auto online Seguro basico para auto Corredor de seguros"

Art Deco / ja taiteet / i konsten / and the arts

6 June 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Scientific editor: Laura Gutman

Scientific editor: Laura Gutman

Editor: Susanna Luojus

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (the Finnish Literature Society), 2013. 179 p., ill.

Texts in Finnish and Swedish, summaries in English

ISBN 978-952-222-430-9

€38, hardback

This work was published simultaneously with the opening of the exhibition ‘Art Déco and the Arts. France–Finlande 1905–1935’, running at the Amos Anderson Art Museum in Helsinki from March to 21 July. Antiquity was the primary source of inspiration for this broad artistic movement in France, after the breakthrough of Fauvism in 1905. In Finland this antimodern – and yet at the same very modern – movement manifested itself most clearly in industrial art, in the 1920s in classicism and 1930s in functionalism. But from early on, Finnish painters and sculptors also kept an eye on the French art and artists – among them Maurice Denis, the spokesman of the antimodernists. The dialogue between the visual and the performative arts (theatre and dance) in Finland is also examined. Samples of Art Deco architecture are mostly absent, as the emphasis is on painting and sculpture. Some less well-known artists of the period (painter Nikolai Kaario, sculptor and engraver Eva Gyldén) are introduced. The exhibition and the richly illustrated book introduce both Finnish and French works – from many museums and collections in France – of both industrial and fine arts, in pictures and in words by nine specialists, offering the reader fresh and interesting comparisons.

What’s so great about paper?

17 September 2009 | Articles, Non-fiction

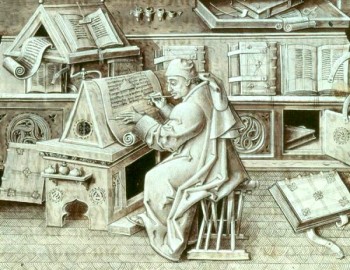

High-tech: the ultimate gadgets of the 15th century, parchment and pen. A portrait of Jean Miélot, the Burgundian author and scribe, by Jan Tavernier (ca. 1456)

The day will soon come when commuters sit on a bus or train with their noses buried in electronic reading devices instead of books or newspapers. Teemu Manninen takes a look at the digital future

Most people interested in books are aware of the arrival of electronic reading devices such as the Amazon Kindle, a kind of iPod — the immensely popular portable music listening device made by the company Apple — for electronic books. For a literary geek like me, the Kindle and e-readers should be the ultimate gadget: a whole library in a small, paperback-sized device. However, I’ve been wondering why digital reading hasn’t become as popular as digital listening. I myself have not invested in an e-reader, although I ought to be exactly the desired kind of customer. After all, I read all the time. Even the mp3 player I have is mostly used for listening to audio books. More…

About us

8 January 2009 |

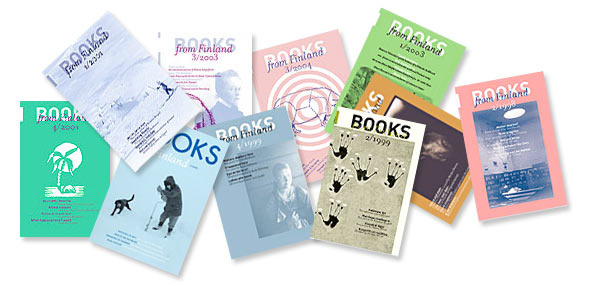

The Books from Finland online journal ceased operation on 1 July 2015, and no new articles will be published on the site.

A comprehensive online archive is available for readers to access. Brief extracts from Books from Finland may be quoted, provided that the source is cited.

If you wish to use longer extracts, please contact .

Books from Finland, an independent English-language literary journal, was aimed at readers interested in Finnish literature and culture. Its online archive constitutes a wide-ranging collection of Finnish writing in English: over 550 short pieces and extracts from longer works by Finnish authors were published from 1967 onwards.

Books from Finland featured classics as well as new writing, fiction and non-fiction, and other materials aimed at giving readers additional information on Finnish society and the wellsprings of Finnish literature. The target audience encompasses literary and publishing professionals, editors, journalists, translators, researchers, students, universities, Finns living abroad and everyone else with an interest in Finland and its literature.

Of course, publishing Finnish and Finland-Swedish literature in English requires skilled translators. Books from Finland’s editorial policy was always to use native English-speaking translators. In recent years David Hackston, Hildi Hawkins, Emily & Fleur Jeremiah, David McDuff, Lola Rogers, Neil Smith, Jill Timbers, Ruth Urbom and Owen Witesman translated for us.

Books from Finland was founded in 1967 and appeared in print format up to the end of 2008. From 2009 to 2015 it was an online publication. The journal’s archives have been fully digitised, and remaining issues will be made available in late 2015.

The Finnish Book Publishers’ Association (Suomen Kustannusyhdistys, SKY) began publishing the print edition of Books from Finland in 1967 with grant support from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture. In 1974 the Finnish Library Association (Suomen Kirjastoseura) took over as publisher until 1976, when it was succeeded by the Helsinki University Library, which remained as the journal’s publisher for the next 26 years. In 2003 publishing duties were handed over to the Finnish Literature Society (Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, SKS) and its FILI division, which remained its home until 2015. The journal received financial assistance from the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture throughout its 48 years of existence.

The editors-in-chief of Books from Finland were Prof. Kai Laitinen (1976–1989), journalist and critic Erkka Lehtola (1990–1995), author Jyrki Kiiskinen (1996–2000), author and journalist Kristina Carlson (2002–2006), and journalist and critic Soila Lehtonen (2007–2014), who had previously been deputy editor. The journal was designed by artist and graphic designer Erik Bruun from 1976 to 1989 and thereafter by a series of graphic designers: Ilkka Kärkkäinen (1990–1997), Jorma Hinkka (1998–2006) and Timo Numminen (2007–2008).

In 1976 Marja-Leena Rautalin, the director of the Finnish Literature Information Centre (now known as FILI), became deputy editor of Books from Finland. She was succeeded by Anna Kuismin (neé Makkonen), a literary scholar. Soila Lehtonen served as deputy editor from 1983 to 2006. Hildi Hawkins, who had been translating texts for the journal since the early 1980s, held the post of London editor from 1992 until 2015.

The editorial board of Books from Finland was chaired from 1976 to 2002 by chief librarian Esko Häkli, from 2004 to 2005 by the Secretaries-General the Finnish Literature Society, Jussi Nuorteva and Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, and from 2006 to 2015 by Iris Schwanck, director of FILI. Members of the board included literary scholars, journalists, authors and publishers.

This history of Books from Finland was compiled by Soila Lehtonen, who served as the journal’s deputy editor from 1983 to 2006 and editor-in-chief from 2007 to 2014. English translation by Ruth Urbom.

New from the archive

26 March 2015 | This 'n' that

This week, a cluster of pieces from and about left-leaning Tampere, the ‘Red City’ of Finland

The Tampella and Finlayson factories, 1954, Tampere. Photo: Veikko Kanninen, Vapriikki Photo Archives / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Also known as the ‘Manchester of Finland’ for its 19th-century manufacturing tradition, Tampere – or rather the suburb of Pispala – produced two important, and strongly contrasting, writers, Lauri Viita (1916-1965) and Hannu Salama (born 1936). Both formed part of a group of working-class writers who emerged after the Second World War, many of whom had not completed their school careers and whose confidence arose from independent, auto-didactic, reading and study.

To understand the place from which these writers emerged, it has to be remembered that there is more to Tampere than a proud radical tradition. As Pekka Tarkka remembers in his essay, the Reds were the losing side in the Finnish civil war of 1918, and for years afterwards they formed ‘a sort of embattled camp in Finnish society’. History is always written by the winners, and authors like Viita and Salama played an important role in giving the Red side back its voice.

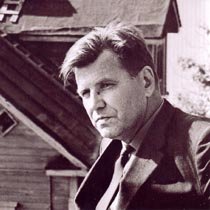

Lauri Viita.

Lauri Viita celebrated Tampere by offering an image of it that is, as Tarkka remarks, ‘poetic, deterministic and materialist’. His poetry differed sharply from the modernist verse of contemporaries such as Paavo Haavikko and Eeva-Liisa Manner, both of whom we have featured recently in our Archive pieces, which abandoned both fixed metres and end-rhymes. His work was an often heroic celebration of the ordinary life of proletarian Tampere, and the more traditional form into which it breathed new life made it accessible. My own mother, for example, who had grown up the child of a Red working-class family far away to the north, in Kajaani, steeped in the rolling cadences of poets such as Aaro Hellaakoski and Uuno Kailas, never really got the hang of Haavikko, or Manner; but she loved Viita.

Here we publish a selection of Viita’s poems, translated by Herbert Lomas, who does an excellent job of capturing his easy-going, unselfconscious rhythms. The introduction is by Kai Laitinen.

Hannu Salama.

Photo: Ptoukkar / CC BY-SA 3.0

Salama is a far more politicised writer than Viita, and he is writing about a Tampere that is already in decline. In his major work, Siinä näkijä missä tekijä (‘No crime without a witness’, 1972), he writes about the travails of the communist minority, doomed to slow extinction – the same band of fellow-travellers to which my grandfather in Kajaani belonged. My mother wasn’t a Salama fan, though – I think his Tampere wasn’t beautiful, or heroic, enough. As someone who had moved far away, to England, she wanted to celebrate, not to mourn.

Here we publish a short story, Hautajaiset (‘The funeral’), which was written at the same time as Siinä näkijä missä tekijä. It’s an unvarnished account of a Tampere funeral which is, at the same time, the funeral of the old, radical way of life – which, sure enough, has vanished almost as if it never existed. As Pekka Tarkka writes of Salama’s short story and the revolutionary songs which run through it: ‘There will be no more singing of communist psalms, or fantasies of the family and of the revolutionary spirit.’

As Marx didn’t say, all that seemed so solid has melted, irretrievably, into air.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues, with a total of 380 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Goodbye darling

30 March 2005 | Fiction, poetry

Poems from Niin kovaa se tuuli löi (‘So bitterly the wind struck’, Tammi, 2004)

Lord, you've promised to come, don't hang back.

Here we are already, sitting, me and the dogs,

and the others that have to go.

Jesus, poor thing, didn't know whom to bloom for,

just kept on lugging his cross, pretty as a pony.

He came and shot us down,

bullets flying without his even noticing.

The night was gifted with roses

full of love.

Through a woman we came here, through a man

we leave.

The attentive lover

31 December 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

In this short story, from his collection Pronssikausi (‘The bronze age’, 1988, on the Finlandia Prize shortlist in 1989), Martti Joenpolvi takes up the subject of the problematic transportation of a human cargo

He braked abruptly; the woman lurched forward, straining against the seat belt, and the car drove into the parking space. The only vehicle parked there was a solitary trailer loaded with timber: a resinous pulpwood-odour came wafting through their open window, so physical, it was as if someone were snooping into the car’s most intimate interior. When they stopped, they got the whiff of a yellow refuse bin, incubated in the heat of the day.

‘What’s up?’

‘We’ve got a problem.’ More…

Breton without tears

31 March 1994 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Extracts from Euroopan reuna (‘The edge of Europe’, Otava, 1982). Introduction by H. K. Riikonen

I am reading a book, it says pour l’homme latin ou grec, un forme correspond à un être; pour le Celte, tout est metamorphose, un même individu peut prendre des apparences diverses, so it says in the book. A strange claim, considering that the word metamorphosis is Greek, and that the best-known book about metamorphoses, Ovid’s Metamorphoseon libri XV was written in Latin. In the myths of all peoples, at least the ones whose oral poetry was recorded in time, such as the Greeks, Serbs, Slavs, Finns, or Aztecs, metamorphoses play a very important part, the Celts are not an exceptional tribe in this respect. The author must mean that the Celts still live in mythical time, the time of metamorphoses when the human being assumed shapes, was able to fly as a bird, swim as a fish, howl as a wolf, and to crown his career by rising up into the sky as a constellation. Brittany is part of the Armorica Joyce tells us about in Finnegans Wake, that book is incomprehensible if one does not know Ireland, and now I see that Brittany is the key to one of the book’s locked rooms. I thought I already had keys to all the rooms after Dublin, the Vatican, and Athens, but one door was and remained closed, the key is here now, in my hand, I can get into all the rooms in the book, and I am home even if I should happen to get lost. The room creates the person, she becomes another when she goes from one room to another, this is metamorphosis, and when she leaves the house she disappears, she no longer exists. The legend on the temple at Delphi, gnothi seauton, know thyself, has led Occidentals onto the false track that is now becoming a dead end, polytheistic religions correspond to the order of nature, but as soon as the human starts to imagine that she knows herself, as soon as the metamorphic era ends, monotheism is born, the human being creates god in her own image, and that is the source of all evil. Planted like traffic signs at the far end of this cul-de-sac stand the hitlers and brezhnevs and reagans and thatchers, new leaves are appearing on the trees, the sun is shining. Landet som icke är* är en paradox: landet blev befintligt därigenom att Edith Södergran sade att det icke är. On the sea sailed a silent ship*, as I tracked my shoeprints across the sand on the beach, it was like walking on a street made out of salty raw sugar, I felt desolate. The wind bent the grasses, the sun warmed the back of my sweater, of course the sun always has the last word, I thought, things should be as they are, this thought gave me peace of mind. I walked past the cows, two of them already chewing the cud, the others still grazing, they stood in a line and raised their heads, stood at attention, as it were, as I walked past. I was not entirely sure that I was heading in the right direction, but then I saw the boucherie and knew that there was a café nearby. Madame greeted me in a friendly fashion, brought me a calvados and a beer and sat down for a chat, wanted to know if I liked the countryside here. I said that things looked the same here as in Ireland, she said that was true, but she had never been to Ireland. I finished my drinks and paid, left, decided to walk along the beach. I saw gun emplacements and two bunkers. I crawled into a bunker. Inside, it was dark and damp. I looked through the embrasure at the sea. I thought of the boys who had been incarcerated here. They had been given a death sentence. I examined a rusty object, what was it, I looked at it more closely, it was an axle from a gun’s undercarriage. As I arrive in my home yard, I note that the lilacs are beginning to bloom. More…

Archives open!

12 December 2014 | This 'n' that

Illustration: Hannu Konttinen

For 41 years, from 1967 to 2008, Books from Finland was a printed journal. In 1976, after a decade of existence as not much more than a pamphlet, it began to expand: with more editorial staff and more pages, hundreds of Finnish books and authors were featured in the following decades.

Those texts remain archive treasures.

In 1998 Books from Finland went online, partially: we set up a website of our own, offering a few samples of text from each printed issue. In January 2009 Books from Finland became an online journal in its entirety, now accessible to everyone.

We then decided that we would digitise material from the printed volumes of 1976 to 2008: samples of fiction and related interviews, reviews, and articles should become part of the new website.

The process took a couple of years – thank you, diligent Finnish Literature Exchange (FILI) interns (and Johanna Sillanpää) : Claire Saint-Germain, Bruna di Pastena, Merethe Kristiansen, Franziska Fiebig, Saara Wille and Claire Dickenson! – and now it’s time to start publishing the results. We’re going to do so volume by volume, going backwards.

The first to go online was the fiction published in 2008: among the authors are the poets Tomi Kontio and Rakel Liehu and prose writers Helvi Hämäläinen (1907–1998), Sirpa Kähkönen, Maritta Lintunen, Arne Nevanlinna, Hagar Olsson (1893–1979), Juhani Peltonen (1941–1998) and Mika Waltari (1908–1979).

To introduce these new texts, we will feature a box on our website, entitled New from the archives, where links will take you to the new material. The digitised texts work in the same way as the rest of the posts, using the website’s search engine (although for technical reasons we have been unable to include all the original pictures).

![]()

By the time we reach the year 1976, there will be texts by more than 400 fiction authors on our website. We are proud and delighted that the printed treasures of past decades – the best of the Finnish literature published over the period – will be available to all readers of Books from Finland.

The small world of Finnish fiction will be even more accessible to the great English-speaking universe. Read on!

Forest and fell

8 May 2013 | Reviews

From North to South: young Heikki Soriola on his way to represent Utsjoki in Helsinki, in 1912. Photo from Saamelaiset suomalaiset

Veli-Pekka Lehtola

Saamelaiset suomalaiset: Kohtaamisia 1896–1953

[Sámi, Finns: encounters 1896–1953]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 528 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-331-9

€53, hardback

Leena Valkeapää

Luonnossa: Vuoropuhelua Nils-Aslak Valkeapään tuotannon kanssa

[In nature, a dialogue with the works of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2011. 288 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5870-54-1

€40, hardback

The study of the Sámi people, like that of other indigenous peoples, has become considerably more diverse and deeper over recent decades. Where non-Sámi scholars, officials and clergymen once examined the Sámi according to the needs and values of the holders of power, contemporary scholarship starts out from dialogue, from an attempt to understand the interactions between different groups. More…

The Othello of Sand Alley

31 March 1989 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

Eeva-Liisa Manner’s Woyzeck is an independent ending to Georg Büchner’s fragmentary play. Introduction by Riitta Pohjola

PROLOGUE

(Dawn in the market square of Leipzig. A gallows looms, dimly visible in the distance. Brisk rumble of drums.)

1st WOMAN

What’s going on here?

1st MAN

They’re getting ready for an execution. Some villain’s going to be executed in public.

1st WOMAN

Who?

2nd WOMAN

Franz Woyzeck. I guess you know him, the barber. More…

Across Europe

30 June 1990 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Mika Waltari (1908–1979) was a prolific writer, journalist and translator. In addition to historical novels, he wrote short stories, travel books, thrillers, plays, books for children, film scripts and poetry. The newly independent Finland of the 1920s, as it emerged from a traumatic period of civil war, declared that its windows were open to Europe, and Waltari’s first novel Suuri illusioni (‘The great illusion’), written in Paris when he was only 19, represents urban romanticism and the world of European capitals.The optimism and enthusiasm for modern life of the 1920s are strongly present in Waltari’s travelogue, Yksinäisen miehen juna, (‘Lonely man’s train’; 1929), an account, both ironic and engagingly naïve, of a great adventure in Europe after the post-1918 redrawing of the continent’s map. The book’s motto is a phrase from Paul Morand, a writer Waltari admired: ‘How is it possible to remain stationary when time slips like ice through our hot hands.’ This work of Waltari’s youth has never before been translated. The author travels by ship and train as far as Turkey; in the following extract, he has reached Hungary

Yksinäisen miehen juna (‘Lonely Man’s train’)

How adorable express trains are – the mighty engines, the rhythm of the rails, the sway of the carriages, the flashing-by of the milestones, the gravel embankments contracting into speeding lines. A train is the only place you can be completely at ease, free from heartache, free from longing, free from tormenting thoughts. Whenever I die, I hope it will be on a train flashing towards some unknown town at eighty miles an hour, with mountains looming on the horizon, and the points lighting up in the descending dusk…. More…

Bring on the white light

12 December 2013 | Fiction, Prose

Extracts from the novel Auringon ydin (‘The core of the sun’, Teos, 2013). Introduction by Outi Järvinen

Jare, March 2017

‘We call the chilli the Inner Fire that we try to tame, just as our forefathers tamed the Worldly Fire before it.’

Mirko pauses dramatically, and Valtteri interrupts. ‘Eusistocratic Finland offers us unique opportunities for experimentation and development. Once all those intoxicants affecting our neurochemistry and the nervous system have been eradicated from society, we will be able to conduct our experiments from a perfectly clean slate.’

‘We fully understand the need to ban alcohol and tobacco. These substances have had significant negative societal impact. And though in hedonistic societies it is claimed that drinks such as red wine can, in small amounts, promote better health, there is always the risk of slipping towards excessive use. All substances that cause states of restlessness and a loss of control over the body have been understandably outlawed, because they can cause harm not only to abusers themselves but also to innocent bystanders,’ Mirko continues.

This is nothing new to me, but I must admit that the criminalisation of chillies has always been a mystery to me. By all accounts it is extremely healthy and contains all necessary vitamins and antioxidants. A dealer that I met once told me that people in foreign countries think eating chillies can lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels – and even prevent cancer. If someone makes a pot of tom yam soup, sweats and pants over it and enjoys the rush it gives him, how is that a threat, either to society or to our health? More…

Elina Brotherus & Riikka Ala-harja

The passing of time

2 March 2015 | Extracts, Fiction, Prose

In 1999 the Musée Nicéphore Niépce invited the young Finnish photographer Elina Brotherus to Chalon-sur-Saône in Burgundy, France, as a visiting artist.

After initially qualifying as an analytical chemist, Brotherus was then at the beginning of her career as a photographer. Everything lay before her, and she charted her French experience in a series of characteristically melancholy, subjective images.

Twelve years on, she revisited the same places, photographing them, and herself, again. The images in the resulting book, 12 ans après / 12 vuotta myöhemmin / 12 years later (Sémiosquare, 2015) are accompanied by a short story by the writer Riikka Ala-Harja, who moved to France a little later than Brotherus.

In the event, neither woman’s life took root in France. The book represents a personal coming-to-terms with the evaporation of youthful dreams, a mourning for lost time and broken relationships, a level and unselfpitying gaze at the passage of time: ‘Life has not been what I hoped for. Soon it will be time to accept it and mourn for the dreams that will never come true. Mourn for the lost time, my young self, who no longer exists.’

1999 Mr Cheval’s nose

The last lap

30 June 2001 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Ilmatasku (‘Air pocket’, Otava, 2000). Introduction by Soila Lehtonen

Father arrived by taxi with his black suitcases.

He stood in the hallway, casting a glance over father’s shoes, his trouser-legs. Under his arm was a folded newspaper; it fell to the ground when father bent to undo his shoelaces.

The newspaper was written in strange letters. It felt as if the saliva would not leave his mouth however hard he swallowed. Mother jumped back and forth; mother’s mouth chattered. He scratched the wall with his nail; it was scored with pencil lines recording how much he had grown.

When father straightened up, he filled the whole room. More…