In the news

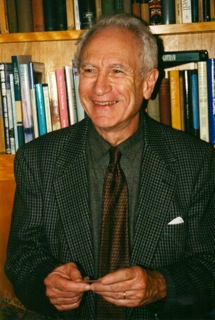

In memoriam Veijo Meri 1928-2015

29 June 2015 | In the news

Veijo Meri. Photo: Irmeli Jung / Otava.

The writer Veijo Meri died on 21 June after a long illness.

Best-known for his war fiction, Meri was one of the towering figures of Finnish literature in the second half of the 20th century. Born in Viipuri in eastern Finland, subsequently ceded to the Soviet Union, he wrote novels, short stories, poetry, stage and radio plays and essays.

He came to prominence with his novel Manillaköysi (‘The manila rope’, 1957), which tells the tragicomic story of a soldier who tries to smuggle a rope home from the front during the Second World War. War and the army were central subjects for this anti-war writer, who deals with his subject with caustic humour, often focussing on loneliness, anxiety and sexual pressures.

A fresh voice in Finnish prose, breaking with its realist tradition, Meri was a film buff who used rapid changes of angle, compression and close-up to emphasise the strangeness and inexplicability of what he wrote about. His is manly prose, much admired by high-achieving male readers. Among the work we have published in Books from Finland is Underage, a short story that brilliantly illustrates Meri’s terse, masculine style; it is accompanied by an interview by Maija Alftan and Meri’s own essay on the art of the short story.

Meri’s minimalist style has something in common with American authors such as Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Chandler, and with the film-makers Sergei Eisenstein, Charlie Chaplin and Ingmar Bergman.

A prodigious talker and reader as well as a writer, Meri was very much at home in his skin. ‘You tend to avoid thinking about death,’ he wrote at the onset of middle age, because it seems a pity that you will have to leave the world, now that you finally feel at home here.’

Meri’s work has been translated into 24 languages.

Books from Finland to take archive form

22 May 2015 | In the news

The following is a press release from the Finnish Literature Society.

The Finnish Literature Society is to cease publication of the online journal Books from Finland with effect 1 July 2015 and will focus on making material which has been gathered over almost 50 years more widely available to readers.

Books from Finland, which presents Finnish literature in English, has appeared since 1967. Until 2008 the journal appeared four times a year in a paper version, and subsequently as a web publication. Over the decades Books from Finland has featured thousands of Finnish books, different literary genres and contemporary writers as well as classics. Its significance as a showcase for our literature has been important.

The major task of recent years has been the digitisation of past issues of the journal to form an electronic archive. The archive will continue to serve all interested readers at www.booksfromfinland.fi; it is freely available and may be found on the FILI website (www.finlit.fi/fili).

Much is written in English and other languages about Finnish literature: reviews, interviews and features appear in even the biggest international publications. The need for the presentation of our literature has changed. Among the ways in which FILI continues to develop its remit is to focus communications on international professionals in the book field, on publishers and on agents.

The reasons for ceasing publication of Books from Finland are also economic. Government aid to the Finnish literature information centre FILI, which has functioned as the journal’s home, has been cut by ten per cent.

Books from Finland was published by Helsinki University Library from 1967 to 2002, when the Finnish Literature Society took on the role of publisher. FILI has been the body within the Finnish Literature Society that has been responsible for the journal’s administration, and it is from FILI’s budget that the journal’s expeses have been paid.

Enquiries: Tuomas M.S. Lehtonen, Secretary General of the Finnish Literature Society, telephone +358 40 560 9879.

In memoriam Austin Flint (1931–2015)

2 April 2015 | In the news

Austin Flint

The playwright, teacher and translator Austin Flint died in New York on 1 February.

Austin was Adjunct Professor in the Department of Arts at Columbia University, New York, and taught playwriting there for almost half a century. Among the translations from Finnish into English he made – together with his wife Aili Flint – are the novel The Parson’s Widow (Hänen olivat linnut) by Marja-Liisa Vartio and the play Anna-Liisa by Minna Canth.

Austin’s plays include: The Flaming Spider: Jonathan Edwards in Northhampton, Prison Light, Marching to Jubilee: William Lloyd Garrison’s Campaign for the Abolition of Slavery and Compartments. His work has been performed in New York and at Yale University.

Austin Flint was a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Books from Finland from 1985 to 1995. With Aili – whom he met in 1958 in Helsinki, where he was teaching – he translated many articles and extracts for the journal.

The Flints acted as hosts in 1986 when the Editorial Board of Books from Finland visited New York to discuss the development of the journal with them and a few selected literary figures. The Editorial Board found Austin’s expertise and interest in making Finnish literature better known in the United States most useful and encouraging. We remember Austin as a warm-hearted collaborator whose gentle humour greatly enlivened the editorial process.

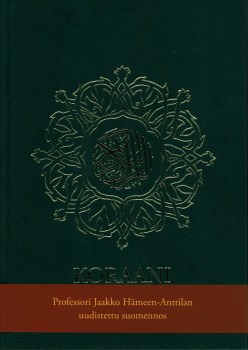

Holy book

26 February 2015 | In the news

The Koran, Koraani, translated into Finnish by Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila.

In an unprecedented project, the Koran, the holy book of Islam, is to be read on the Radio 1 channel of the Finnish Broadcasting Company (YLE) in 60 half-hour segments. Made with considerable input from the Finnish Muslim community, the series is not, however, part of YLE’s religious broadcasting, but is intended to increase people’s knowledge of the Koran and Muslim culture in general.

‘It is important that the Koran is read in its entirety, and not just select items that show that Islam is bad and violent or good and beautiful,’ says the translator, Professor Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila. The broadcasts are to be preceded by conversations between Professor Hämeen-Anttila and Imam Anas Hajjar, a leader of the Finnish Muslim community, exploring the religious and historical context of the day’s text. According to Hämeen-Anttila, the two men discussed ‘everything between heaven and earth’ during the recordings. Among other things they consider the role of Satan, instructions on suitable behaviour for men when in the company of women, and the Ayat an-Nur, or ‘Verse of Light’, an Arabic text found on the wall of many Muslim homes.

Islam, numbering an estimated 40,000 believers, is a minority religion in Finland, whose two official denominations are the Lutheran and Greek Orthodox churches. The first Muslims to come to Finland were Tatars from Russia in the 19th century; most, however, arrived after 1990, mainly from Africa and the Middle East.

‘The programme is an important step in understanding one another. It is an attempt to tell the story of The Koran and what it contains,’ says Imam Hajjar.

The series begins on 7 March.

Not joined up

19 February 2015 | In the news

Photo: Brad Flickinger / CC BY 2.0

The news that Finnish schools are to stop teaching cursive writing, in favour of a new emphasis on touch typing and the most efficient way of composing a text message, has been widely reported in the British press.

But not in our household.

With three children – aged 13, 9 and 6 – all struggling, to a greater or lesser degree, to make sense of the curlicues of joined-up writing as it’s taught in British schools, the pressure to abandon school in London and move to Finland would be all but irresistible if they every got to hear the news.

With letter-forms that bear little resemblance to printed characters and a loopy style, apparently derived from old-fashioned copperplate, that few children are going to be able to master completely, let alone develop into an elegant mode of handwriting, joined-up handwriting remains for many an obstacle to, not a means of, communication.

Added to the benefits of Finnish schools my children already know about – the shorter working days, the lighter homework load, the absence of school uniforms, the good school meals, the outdoor breaks every hour – the news that not only will Finnish schoolchildren not be expected to develop good handwriting, but will be issued with tablets on which to practise their computer skills, would axe their enthusiasm for school at home in Britain.

For their mother, the puzzle remains how Finland manages to employ such child-friendly school policies and still remain close to the top of the global Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessments. The trick seems to be to recruit top-level graduates into well-run teacher training schemes, pay them well, and to trust them to do their job as teachers, without the mounds of paperwork and need for incessant testing that bedevil the job in Britain.

About the handwriting, my children will find out soon enough, when their friends in Finland come home carrying not exercise books but tablets.

But meanwhile, I’m keeping my fingers crossed they don’t see this piece.

Poets, pastries and prizes

5 February 2015 | In the news

Joni Skiftesvik. Photo: Hilkka Skiftesvik

The Runeberg Prize for fiction is awarded to Joni Skiftesvik (67) for his autobiographical novel Valkoinen Toyota vei vaimoni (‘The white Toyota took my wife’).

Today, 5 February, is celebrated in Finland as the birthday of the poet J.L. Runeberg (1804-1877), known as the Finnish national poet, and writer – among many other things – of the lyrics of the national anthem.

In addition to the eating (in the Books from Finland offices, at least) of the rather delicious Runeberg cakes, it is also marked by the annual award of the Runeberg Prize, worth 10,000 euros.

The book tells the often harrowing story of Skiftesvik’s family, including illness, estrangement and death. In making the award, the jury commented: ‘This story appeals to the emotions, it touches the reader; but most important of all, after the book is closed, a miracle happens: its weighty content lives on in the mind, growing day by day. Many good novels have been written, but a masterpiece is recognised from its lasting effects.’

Runeberg’s favourite. Photo: Ville Koistinen

And the winner is… Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2014

27 November 2014 | In the news

Jussi Valtonen. Photo: Markko Taina

The winner of the prize this year, worth €30,000 and awarded on 27 November, is He eivät tiedä mitä he tekevät (‘For they know not what they do’, Tammi) by Jussi Valtonen (born 1974), a psychologist and writer. The novel – 558 pages – is his third: it focuses on the relationship of science and ethics in the contemporary world, with an American professor of neuroscience, married to a Finn, as the protagonist.

Professor Anne Brunila – who has worked, among other posts, as a CEO in forest and energy industry – chose the winner. In her awarding speech she said: ‘The novel is an astonishing combination of perceptive description of human relationships, profound moral and ethical reasoning, science fiction and suspense…. I have never encountered a Finnish portrayal of our present era that is anything like it.’

The other five novels on the shortlist of six were the following:

Kaksi viatonta päivää (‘Two innocent days’, Gummerus) by Heidi Jaatinen is a story of a child whose parents are not able to take care of her; Olli Jalonen’s Miehiä ja ihmisiä (’Men and human beings’, Otava) focuses on a young man’s summer in the 1970s. Neljäntienristeys (‘The crossing of four roads’, WSOY), a first novel by Tommi Kinnunen, is a story set in the 20th-century Finnish countryside over three generations. Kultarinta (‘Goldbreast’, Gummerus) by Anni Kytömäki is a first novel about generations, set in the years between 1903 and 1937, celebrating the Finnish forest and untouched nature. Graniittimies (‘Granite man’, Otava) by Sirpa Kähkönen portrays a young, idealistic Finnish couple who move to the newly-founded Soviet Union to work in the utopia they believe in.

A long list of good novels

27 November 2014 | In the news

The longlist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award 2015 has been announced and, among the 142 translated novels – from 39 countries and 16 original languages – are two from Finland.

The longlist for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award 2015 has been announced and, among the 142 translated novels – from 39 countries and 16 original languages – are two from Finland.

Mr Darwin’s Gardener by Kristina Carlson (Peirene Press, UK, 2012), a novel set in the 1860s England, is translated by Emily and Fleur Jeremiah (see the extracts in Books from Finland).

Cold Courage, a thriller by Pekka Hiltunen (Hesperus Press, UK), is translated by Owen Witesman. Both entries were nominated by Helsinki City Library.

Among the authors writing in English are Margaret Atwood, J.M. Coetzee, Roddy Doyle, Stephen King, Jhumpa Lahiri, Thomas Pynchon and Donna Tartt.

This literary award was established by Dublin City, Civic Charter in 1994. Nominations are made by libraries in capital and major cities throughout the world, on the basis of ‘high literary merit’. In order to be eligible for consideration in 2015 a novel translated into English must be first published in the original language between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2013.

The award for a translated novel is worth €75,000 to the author, €25,000 to the translator. The shortlist of ten titles will be announced by an international panel of judges in April 2015, the winner in June.

We’ll be keeping our fingers crossed for our ex-Editor-in-Chief Kristina Carlson!

‘The Lion of the North’ wins the non-fiction Finlandia Prize

25 November 2014 | In the news

The Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014, worth €30,000 and awarded by Suomen Kirjasäätiö (The Finnish Book Foundation), went to the historian and author Mirkka Lappalainen on 19 November for her book on a 17th-century Swedish king.

Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014, worth €30,000 and awarded by Suomen Kirjasäätiö (The Finnish Book Foundation), went to the historian and author Mirkka Lappalainen on 19 November for her book on a 17th-century Swedish king.

The winning entry, entitled Pohjolan leijona, Kustaa II Adolf ja Suomi 1611–1632 (‘The Lion of the North. Gustavus II Adolphus and Finland 1611–1632’, Siltala), was chosen by from a shortlist of six finalists by Heikki Hellman, journalist and Dean of the School of Communication, Media and Theatre in Tampere. According to him, ‘Pohjolan leijona is an exceptionally well-written narrative for a non-fiction book; the author uses both earlier literature and numerous primary and secondary sources with great skill. Lappalainen succeeds in demonstrating how, during the reign of Gustavus II Adolphus, both Sweden and its easterly province, Finland, began to develop an organised society with its structure of officials and bureaucracy, how jurisdiction replaced the arbitrary rule of the aristocracy and how it was only then that Finland developed its role as part of Sweden. Pohjolan leijona sweeps the reader along and helps us to understand where we have come from and who we are.’

Hellman also commented on the growing practice of publishing non-fiction texts in English only: ‘Research is not done only for other scholars; it must also be relevant to people’s lives and be brought to their attention. We must also publish in our mother tongue, or else it will not survive as a language for research. This is one of the reasons why non-fiction is so necessary.’

Mirkka Lappalainen has received other prizes for her work. Susimessu (‘Wolf mass’), for example, was voted History Book of the year in 2010.

The Finlandia Junior Prize 2014

20 November 2014 | In the news

Maria Turtschaninoff’s third fantasy book for young people, Maresi. Krönikor från röda klostret / Maresi. Punaisen luostarin kronikoita (‘Maresi. Chronicles of the Red Convent’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation by Marja Kyrö, publisher Tammi) was awarded the Finlandia Junior Prize, worth €30,000, on 20 November.

Maria Turtschaninoff’s third fantasy book for young people, Maresi. Krönikor från röda klostret / Maresi. Punaisen luostarin kronikoita (‘Maresi. Chronicles of the Red Convent’, Schildts & Söderströms; Finnish translation by Marja Kyrö, publisher Tammi) was awarded the Finlandia Junior Prize, worth €30,000, on 20 November.

The winner was chosen by the scriptwriter and film director Johanna Vuoksenmaa who, in her awarding speech, said that it is ‘an exceptionally powerful fantasy book which, in addition to telling an exquisite, wise and exciting story, also provides a welcome correction to the gender division of fantasy book characters, which has been slightly skewed ever since Tolkien. Maresi reminds me that even today there are places in the world where readers are not sought for books, where knowledge is not on offer to young, thirsty minds. People’s opportunities to know and learn are limited and human rights trampled upon.’

The other five candidates were the following:

Written and illustrated by Saku Heinänen, Zaida ja lumienkeli (‘Zaida and the snow angel’, Tammi) is the story of a little girl whose school days are not always happy; Puiden tarinoita. Puuseppä (‘Stories by trees. The carpenter’, Books North) is a fairy-tale written by Iiro Küttner and illustrated by the graphic artist and cartoonist Ville Tietäväinen; Jyri Paretskoi’s first novel Shell’s Angles ja Kalajoen hiekat (‘Shell’s Angles and the Kalajoki sands’, Karisto) is a humorous story for young teenagers; Min egen lilla liten / Oma pieni pikkuruinen (‘My own tiny little thing’, Schildts & Söderströms, Teos) is a picture story about longing for closeness told by Ulf Stark and illustrated by Linda Bondestam; a picture book about a little squirrel by Mila Teräs, Olga Orava ja metsän salaisuus (‘Olga Squirrel an the forest’s secret’, Lasten Keskus) is illustrated by Karoliina Pertamo.

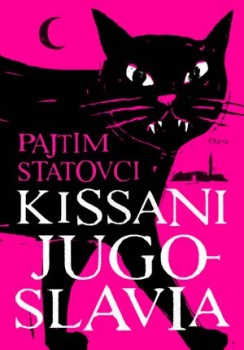

Prize for the best debut book

20 November 2014 | In the news

The Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for the best first work, written in Finnish, for 2014 was awarded on 13 November to Kosovo-born Pajtim Statovci, 24, for his novel Kissani Jugoslavia (‘Yugoslavia my cat’, Otava – see translated extracts here).

The Helsingin Sanomat literature prize for the best first work, written in Finnish, for 2014 was awarded on 13 November to Kosovo-born Pajtim Statovci, 24, for his novel Kissani Jugoslavia (‘Yugoslavia my cat’, Otava – see translated extracts here).

The choice was made by a five-strong jury from a total of 65 books. The prize, which was this year awarded for the 20th time, is worth €15,000.

Among the ten finalists were a collection of essays, three collections of poetry and six novels. According to the jury, Statovci’s novel, ‘drowns the reader, after a realistic description of events, in a dreamlike, lyrical vision. This kind of writing is not taught anywhere. The skill either resides in the writer or it doesn’t.’

Shortlist for Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014

13 November 2014 | In the news

The shortlist for the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014 – worth €30,000 – was announced on 5 November by the chairperson of the jury, Susanna Pettersson, Director of the Ateneum Art Museum. The works on the list of six are as follows:

The shortlist for the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction 2014 – worth €30,000 – was announced on 5 November by the chairperson of the jury, Susanna Pettersson, Director of the Ateneum Art Museum. The works on the list of six are as follows:

Pohjolan leijona, Kustaa II Adolf ja Suomi 1611–1632 (‘The lion of the North. Gustavus II Adolphus and Finland 1611–1632’, Siltala) by the historian and author Mirkka Lappalainen deals with the implications of actions of the mighty Swedish king on the part of the kingdom that was known as Finland.

Herkkä, hellä, hehkuvainen – Minna Canth (‘Sensitive, gentle, radiant – Minna Canth’, Otava) is a fresh biography of the Finnish pre-feminist author (1844–1897), a popularised version of a dissertation by Minna Maijala.

Karanteeni. Kuinka aids saapui Suomeen (‘Quarantine. How Aids came to Finland’, Siltala) by Hanna Nikkanen & Antti Järvi records the history of the disease, its arrival and consequences in Finland.

Operaatio Elop (‘Operation Elop’, Teos) by Pekka Nykänen & Merina Salminen is the story of the mobile phone company Nokia in its declining years and its Canadian CEO (2010–2013) Stephen Elop, who did not become the saviour of the company on the global market.

Usko, toivo ja raskaus. Vanhoillislestadiolaista perhe-elämää (‘Faith, hope and pregnancy’, Atena) by Aila Ruoho &Vuokko Ilola focuses on the family life, particularly the status of the woman, of a fundamentalist religious community in Finland.

Tulisaarna. Einojuhani Rautavaaran elämä ja teokset (‘Fiery sermon. Life and works of Einojuhani Rautavaara’, Teos) by Samuli Tiikkaja (journalist, music critic and researcher) is a biography of the composer Einojuhani Rautavaara (born 1928).

The winner – according to the rules of the prize, it will be given to a deserving Finnish generalist non-fiction book – will be chosen by Heikki Hellman, journalist and Dean ofthe School of Communication, Media and Theatre in Tampere, on 19 November.

Winner of the Nordic Council Literature Prize

6 November 2014 | In the news

Kjell Westö. Photo: Kata Portin

The Nordic Council Literature Prize 2014 went to Kjell Westö and his novel Hägring 38 (‘Mirage 38’, 2013; in Finnish, Kangastus 38). The prize, awarded since 1962 and worth €47,000, was given on 29 October at a ceremony in Stockholm.

Among the 13 nominees was another Finn, the poet Henriikka Tavi with her collection Toivo (‘Hope’, 2011).

The jury said: ‘The Nordic Council Literature Prize goes to the Finnish writer Kjell Westö for the novel Mirage 38, the evocative prose of which breathes life into a critical moment in Finland’s history [the time before the Winter War, 1939–1940] – one that has links to the present day.’ Here, more on Westö and his winning novel.

Translation prize to Angela Plöger

23 October 2014 | In the news

Angela Plöger, Frankfurt Book Fair, 8 October. Photo: Katja Maria Nyman

The 40th Finnish State Prize for the Translation of Finnish Literature of 2014 – worth €15,000 – was awarded to the German translator Angela Plöger at the Frankfurt Book Fair on 8 October.

Dr Angela Plöger (born 1942) studied Finnish and Fennistics in Berlin; she first came to Finland in the 1960s after having become interested in the Finnish language as a result of learning Hungarian.

‘I had been to the restaurant at the Helsinki Railway Station where Bertolt Brecht was thinking how the noblest part of a man is his passport, and how Finns are a people who keeps silent in two languages.’

Plöger then defected to West Germany, starting her career anew. She has also translated texts from Hungarian and Russian. In her speech in the Finnish Pavilion of the Book Fair Plöger said that in her opinion translating literature is the most fascinating profession in the world.

Her first translation of a Finnish novel was Tamara, by Eeva Kilpi, published in 1974. Among the most recent of the 40 novels Plöger has translated during the past five decades from Finnish are the novels Kätilö (‘Midwife’, 2011) by Katja Kettu and Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’, 2012) by Sofi Oksanen. Among the other works Plöger has translated are novels by Leena Lander, Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Anja Snellman, Kaari Utrio, Johanna Sinisalo, Risto Isomäki and Antti Tuuri, as well as a number of drama texts by Laura Ruohonen, Juha Jokela, Aki Kaurismäki, Pirkko Saisio and Sofi Oksanen.

The Minister for Culture and Housing, Pia Viitanen, thanked Plöger for her extensive and multi-faceted work in the field of language and literature and in promoting Finnish literary culture in Germany.

The prize, worth € 15,000, has been awarded by the Ministry of Education and Culture since 1975 on the basis of a recommendation by FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

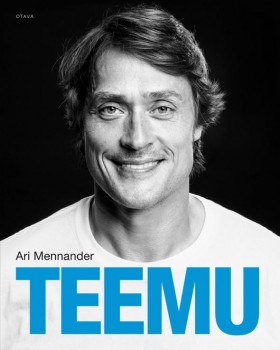

Ice hockey and grumpiness – popular books in September

16 October 2014 | In the news

Ice hockey veteran: Teemu Selänne

The September list of best-selling non-fiction compiled by Suomen Kirjakauppaliitto, the Finnish Booksellers’ Association, included books on mushrooming: a popular pastime that, finding fungi for dinner. However, number one was the biography of the most internationally successful (NHL) ice hockey player so far, Teemu Selänne (recently retired), entitled Teemu (Otava).

Ilosia aikoja, Mielensäpahoittaja (‘Happy times, you who take offence’, WSOY) is the third book in the popular humorous series by Tuomas Kyrö, and it tops the September list of the best-selling Finnish fiction.

Kyrö’s protagonist, this mielensäpahoittaja, the one who ‘takes offence’, is a 80-something grumpy old man living in the countryside and opposing most of what contemporary lifestyles are about. For in the olden days everything was better: for example, food wasn’t complicated and cars were easily repairable.

Apparently Finns can’t get enough of this grumpiness. What began as short monologues written for the radio has become a series of books, and Kyrö’s Mr Grumpy has also appeared on the stage as well as on the screen: the first night of the film, also entitled Mielensäpahoittaja (directed by Dome Karukoski), took place in September. Will there be much more to come, we wonder.

Number two was the latest thriller by Ilkka Remes (pseudonym) with a book entitled Horna (‘Hell’, WSOY), and on third place was the new book by Anna-Leena Härkönen, a novel about a married couple who become lotto winners, Kaikki oikein (‘All correct’, Otava).

First place of the best-selling books for children and young people was occupied by the Moomins – not the original story books or comics by Tove Jansson though, but by other ‘Moomin writers’ and illustrators, whom there have been surprisingly many after Jansson’s Moomin art was made reproducible; this time the book is entitled Muumit ja ihmeiden aika (‘The Moomins and the time of wonders’, Tammi). Another cause of wonder, we think.