Prose

Patsy, the artist of the lumber camps

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Atomintutkija ja muita juttuja (1950). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

Deep in the wilds, where the only sound is the sad, primeval sighing of the forest, it is easy to succumb to a mood of boredom and melancholy. It may sometimes occur to you that in such a place you are wasting your life. Real life goes on elsewhere, in places with more people, more signs of human activity, more light, more gaiety…

You fell a tree, severing a string of that mighty instrument, the forest. You saw it into logs, you strip off the bark: it all seems dull and pointless. Sometimes the rain decides to go on for days: the trees have streaming colds, droplets hang from every needle-tip. You make for the shelter of a lumber camp. But the low-roofed rest-hut, deep in the forest, looks a dreary place, the well-known faces are so dull, the talk so futile. You feel you know in advance what each man is going to say. And the food, too, is just the same as usual, the same old rubbishy mush. The sight of the pot, with its blackened sides, gives no pleasure: you know all too well what is in it. And those grubby playing-cards, how disgusting! The mere sight of them is enough to make you feel defiled… More…

The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Puhalluskukkapoika ja taivaankorjaaja (‘The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer’, 1983). Interview by Olavi Jama

Cold.

A chill west wind came over the blue ice. It went right to the skin through woollen clothes. Shivers ran up and down the spine, made shoulders shake.

In the bank of clouds close to the horizon, right where the icebreaker had crunched open a passage to the shore, hung a pale blotch, a substitute for the sun. It gave off more chill than warmth.

Lennu’s teeth were chattering.

He wore a buttoned-up windbreaker, a hand-me-down from Gunnar, over a heavy lambswool shirt. It couldn’t keep off the cold. More…

The report

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

The power game

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

Hotel for the living

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…

Mirdja

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Mirdja (1908). Introduction by Marja-Liisa Nevala

Now they were in the city – their minds more alive than usual with wilfulness and daring.

For – quite unable to jettison their shared life – they had at least to get on top it… Had to … Every single person has to battle …

And Mirdja’s head was full of efficacious rules for balance, countless cool and wise thoughts – to meet all conflicts.

Lucidly and coldly she had clarified her present position for herself. She was married. Right. No particular joy in that. But no need for any particular disaster in it either. And if she had thrown herself into dependence through this banal arrangement, the sort that everyone has a little of in this life, she had only herself to blame. She had to be able to live by rising above the trivialities of existence. Besides, she had always known that in the final count it was immaterial whom one was married to. A marriage always had its own profile, its dreary distinguishing marks, but one was not compelled to absorb these dreary sides into one’s own being. How did they do it in France? Every year thousands of marriages occur, without an atom of personal liking entering into the game, and extremely seldom are the marriages unhappy. Why so? Mutual politesse: a little of the art of social intercourse, and the whole problem is solved. In the morning a tiny friendly greeting at the breakfast table: ‘Bonjour ma chère,’ – ‘Bonjour, mon ami’; a courteous kiss on the hand, a pretty smile in response, and everything’s as it should be. Because those people know how to go about it. Marriage – one of society’s many empty regimentations! Only stupid people tried, within narrow limits like these, to find fullness of content or idealize. Stupid, Mirdja had been. Comically destructive in that heavy northern solemnity of hers – refusing to acknowledge any form without content, yet fearful of endowing content with any form except the conventional and time-tested. She had lived with a common-or-garden person’s longing for fullness, and then allowed, exactly like that sort of person, her disappointment and bitterness to flood over all her nearest and dearest. She had lived in indiscretion. She had been paltry and rotten and considered herself a slave … More…

The starving, too

Issue 2/1983 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Poems from Det som alltid är (‘What always is’). Introduction by Sven Willner

The starving, too

The starving, too, can

love, but their love is

simplified to hunger, its

principle. With the help of

another’s love the sated love

themselves, which they

otherwise would hate. And

stronger is perhaps the love

that saves,

but deeper is the one that

seals. People, of

whom all that is left is

a heart and its

two arms, give one another

their hunger. More…

And he left the road

Issue 2/1983 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Three short stories from Maantieltä hän lähti (‘And he left the road’). Introduction by Eila Pennanen

And he left the road

And he left the road, walking straight ahead across fields and ditches, past barns and through bushes growing in the ditch. From the fields he went on to the forest, climbed a fence, walked past spruce and pine, juniper bushes and rocks, and came to the edge of a forest and to the swamp. He crossed the swamp, going through small groves of trees if they happened to be in his way. He went on walking rapidly across rivers, through forests, over seas and lakes, and through villages, and finally he came back to the very spot from which he had started walking straight ahead.

In the same way he walked at a right angle to the direction he had first taken and after that, a few times between those two directions. Every time he would start from the road and in the end would always come back to the road in the same direction as when he’d started off. On his rounds, after walking a bit, he would stop and look up every now and then, and each time he looked he would see the sky and sun or the moon and stars. More…

Chronicles of crisis

Issue 4/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Books from Finland presents here an extract from Dyre prins, a novel by the Finland-Swedish writer Christer Kihlman that is to be published in 1983 by Peter Owen of London under the title Sweet Prince, in a translation by Joan Tate.

Christer Kihlman (born 1930) first became known as a poet; but, after publishing two collections of poetry, he turned to novels. He has been branded a merciless scourge of the bourgeoisie. Equally important in his writing, however, are his masterly psychological analyses, his examination of the myriad aspects of the human personality, his sovereign disregard for taboos and his unflagging search for the truth. His books are about crises – the conflict between the generations, between the individual and society, between opposing political ideologies, between homosexual and heterosexual love. As Ingmar Svedberg remarked in an extensive appreciation of Kihlman’s work that appeared in Books from Finland 1-2/1976, ‘In his perceptive moral analyses, his exploration of the depths of human destructiveness and degradation, Kihlman is sometimes reminiscent of Faulkner.’ Since 1970, Kihlman has published three revealing autobiographical works, two of them dealing with his encounter with South America; Dyre prins, first published in 1975, represents a brief interlude of fiction.

The extract printed below is accompanied with a personal appreciation of the novel by its English translator, Joan Tate

Grandfather’s astonishing revelation gave me a new perspective on my life. I had suddenly been given a concrete, genuine foundation for both my hatred and my self-esteem. In a way I took the story of my origins as an extreme confirmation of the rightness of the Communist interpretation of reality, and at the same time it gave me a wonderful, dazzling sensation of being someone, despite everything, of having a place in a meaningful human perspective of time, despite everything, of being a link, however modest, in the historical family tradition. I did not need to found a dynasty; I already belonged to a dynasty, if only a minor branch. One was less important than the other, and even if the two experiences were irreconcilable and contradictory, they existed all the same in the same consciousness, contained within the same consciousness, my consciousness. I, Donald Blad! More…

The Storm • September

Issue 3/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

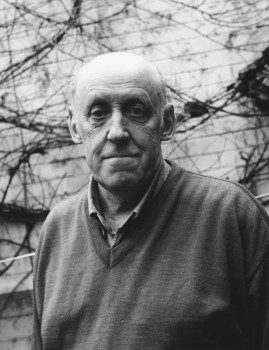

Bo Carpelan. Photo: Charlotta Boucht

Extracts from Jag minns att jag drömde (‘I remember dreaming’, 1979)

The Storm

I remember dreaming about the great storm which one October evening over forty years ago shook our old schoolhouse by the park. My dream is filled with racing clouds and plaintive cries, of roaring echoes and strange meetings, a witch’s brew still bubbling and hissing in the memory of those great yellow clouds.

Our maths teacher – a small sinewy woman who seemed to have swallowed a question mark and was always wondering where the dot had gone, so she directed us in a low voice and with downcast eyes as if we didn’t exist – and yet her little black eyes saw everything that happened in the class, and weasel-like, were there if anyone disobeyed her – was writing the seven times table on the blackboard, when a peculiar light filled our classroom. We looked across at the window; the whole schoolhouse seemed to have been suddenly transformed into a railway station, shaking and trembling, a whistling sound penetrating the cold thick stone walls, and at raging speed, streaky clouds of smoke were sliding past the window, hurtling our classroom forward as if we were in an aeroplane. Our teacher stopped writing and raised her narrow dark head. Without a word, she went over to the window and stood looking out at the racing clouds. More…

Arska

Issue 3/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kaksin (‘Two together’). Introduction by Pekka Tarkka

A landlady is a landlady, and cannot be expected – particularly if she is a widow and by now a rather battered one – to possess an inexhaustible supply of human kindness. Thus when Irja’s landlady went to the little room behind the kitchen at nine o’clock on a warm September morning, and found her tenant still asleep under a mound of bedclothes, she uttered a groan of exasperation.

“What you do here this hour of day?” she asked, in a despairing tone. “You don’t going to work?”

Irja heaved and clawed at the blankets until at last her head emerged from under them.

“No,” she replied, after the landlady had repeated the question.

“You gone and left your job again?”

“Yep.” More…

About calendars and other documents

Issue 2/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Sudenkorento (‘The dragonfly’, 1970). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

I now have. Right here in front of me. To be interviewed. Insulin artist. Caleb Buttocks. I have heard. About his decision. To grasp his nearly. Nonexistent hair and. Lift. Himself and. At the same time. His horse. Out of the swamp into which. He. Claims. He has sunk so deep that. Only. His nose is showing. How is it now, toe dancer Caleb Buttocks. Are you. Perhaps. Or is It your intention. To explain. The self in the world or. The world. In the self. Or is It now that. Just when you. Finally have agreed to. Be interviewed by yourself. You have decided. To go. To the bar for a beer?

– Yes. Can you spare a ten?

– Yes.

– Thanks. See, what’s really happened is that. My hands have started shaking. But when I down two or three bottles of beer, that corpse-washing water as I’ve heard them call it, my hands stop shaking and I don’t make so many typing errors. If I put away six or seven they stop shaking even more and the typing mistakes turn really strange. They become like dreams: all of a sudden you notice you’ve struck it just right. Let’s say, ‘arty’ becomes ‘farty’. Or I mean to say, ‘it strikes me to the core’ I end up typing ‘score’. It’s like that. A friend of mine, an artist, once stuck a revolver in my hand. Imagine, a revolver! I’ve never shot anything with any kind of weapon except a puppy once with a miniature rifle. My God, how nicely it wagged its tail when I aimed at it, but what I’m talking about are handguns, those shiny black steelblue clumps people worship as heaven knows what symbols. It’s not as if I haven’t been hoping to all my life. And now, finally, after I’d waited over fifty years, it turned out that the revolver was a star Nagant, just the kind I’d always dreamed of. So if I ever got one of those, oh, then would sleep through the lulls between shots with that black steel clump ready under my pillow. Well, my friend the artist set out one vodka bottle with a white label and three brown beer bottles with gold labels on the edge of a potato pit – we had just emptied all of them together – stuck the fully loaded star Nagant into my hand, took me thirty yards away and said:

– Oh, Lord. More…

The Session

Issue 2/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Pappas flicka (‘Daddy’s girl’, 1982), an extract of which appears below, is published in Finland by Söderstrom & C:o and in Sweden by Norstedt. The Finnish translation is published by Tammi. Introduction by Gustaf Widén

At first I say nothing, as usual.

Dr Berg also sits in silence. I can hear him moving in his chair and try to work out what he’s doing. Is he getting out pen and paper? Or perhaps he has a tiny soundless tape-recorder he is switching on.

Or is he just settling down, deep down into his armchair, one leg crossed over the other, like Dad used to sit? I used to climb up on to his foot. The he would hold my hands and bounce his foot up and down, and you had to say “whoopsie” and finally with a powerful kick, he would fling me in the air so that I landed in his arms.

I have worked it out that the little cushion under my head is to stop us lunatics from turning our heads round to look at Herr Doktor.

It would certainly be nice to sit bouncing up and down on Dr Berg’s foot. His ankle would rub me between my legs …

I soon start feeling ashamed and blush.

“Mm,” says Dr Berg, as if reading my thoughts. Or can he see my face from where he is sitting? I try rolling my eyes up to catch a glimpse of him, but all I can see is the ceiling with all its thick beams.

“I seem to have been here before,” I say. More…

An end and a beginning

Issue 1/1982 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Det har aldrig hänt (‘It never happened’, 1977). Translated and introduced by W. Glyn Jones

There they are!

Over the ice they ride. The hoofs in rhythmical movement kick up the snow. The trail points north west. The sound of the hoofs is absorbed in the blue twilight of a March evening. The two horsemen push on, close together, passing one tiny island after another. Their eyes are fixed on a trail which has lain before them throughout the day. They are hunting like wolves. Yes, like wolves they are.

Or are they?

The twilight gives way to darkness and the black of night. The riders lean low over their horses in an attempt to follow the trail, but at last one of them raises his hand. The hunt is called off. The horses snort and toss their heads so their manes dance. Clouds of steam rise from them, enveloping the men as they dismount and lead their horses to an islet where the dark and deserted profile of a fisherman’s cabin can be glimpsed. Heaven knows who the hut belongs to, but it is a good thing that it is there with its walls and a roof, a shelter against the night. More…

Choosing a play

Issue 3/1981 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Leiri (‘The camp’). Introduction by Vesa Karonen

The local amateurs were having their theatre club meeting on a Friday evening in the main part of the parish hall. It was late August, the light was beginning to fade and no one had remembered to put the lights on. First the stage grew dark, then the floor, then the ceiling. The light lingered on the inside wall for the longest. There were creaks and groans from the rooms at the back and from the attic. The caretaker had been moving around in there about three in the afternoon, and his traces lingered, as they do in old buildings.

“Something of that sort but short, and it’s got to be bloody funny,” said the chairman, a carpenter called Ranta.

In the store cupboard there were 108 old scripts. Tammilehto, the secretary, hauled out about 30 scripts onto the table. His job was running a kiosk down the road.

“Nothing out of date,” said Ranta.

“There’s got to be a bit of love in it, I say,” said Mrs Ranta.

She had a taxi-driver’s cap on her head and was wearing a man’s grey summer jacket, a white shirt and a blue tie. Her car could be seen from the window. It was in the yard. She always parked her car so it could be seen from inside. More…