Fiction

Eroica

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

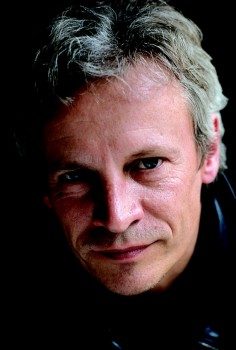

Ilpo Tiihonen. Photo: Irmeli Jung

Poems from From Eroikka (‘Eroica’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Ilpo Tiihonen (born 1950) published his first collection of poetry in 1975. From the beginning, his poems have been couched in the language of the street, and he uses slang liberally. Tiihonen has always been opposed to the miniature idylls of nature that were so characteristic of the 1970s. He aims at the secularisation of poetry, and he uses humour and comedy as a counterweight to high culture. He has evidently been influenced in his technique by Mayakovsky and Yesenin, to whom he often refers in his poems. His preferences in the poetic tradition are apparent in the fresh and liberal new interpretations of poems by Gustav Fröding contained in his collection Eroikka. Unusually for a contemporary Finnish poet, Tiihonen makes extensive use of rhyme. The result is often strongly lyrical poems that could almost be called modern broadsheet ballads, and may also bring Brecht to mind. More…

Bearded Madonna

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Parrakas madonna (‘Bearded Madonna’, 1983). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

The first volume of poems by Eira Stenberg (born 1943) appeared in 1966; since then she has published both poems and children’s stories. In her most recent collection, she examines human relationships within the family, divorce, motherhood and childhood. Stenberg’s voice is clear and concrete. Her treatment of both mother and child is unsentimental, sometimes ironic; perceptively and farsightedly she deals with the importance of childhood in the way it predestines the fate of the individual. No love or hate burns/ like that we receive as a gift from childhood, Stenberg writes in one of her poems. The home – protective, restrictive and punishing – is often the scene of her poems. The man, the father, is the butt of considerable irony and criticism, but Stenberg also destroys the myth of the madonna-like mother and the idyll of the home. More…

An intimation of Paradise

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Poems from Paratiisiaavistus (‘An intimation of Paradise’, 1983). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Satu Salminiitty (born 1959) has published only one collection of poetry since her first appeared in 1981, but with these two volumes she has achieved considerable success. She writes with a fine rhetoric using language and rhythm that are far removed from those of spoken Finnish. Religious pathos has a prominent place in her work, and her poems often derive from praise, prayer or even magic incantations; Salminiitty is a creator of vision who trusts to her metaphysical intuition, a quality not generally discernible among today’s Finnish poets. Equally rare is her lively faith in the goodness and beauty of people and of the world. A conscious rejoinder to materialism, pessimism and fear of the future can be read in her poems. More…

Narcissus in winter

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

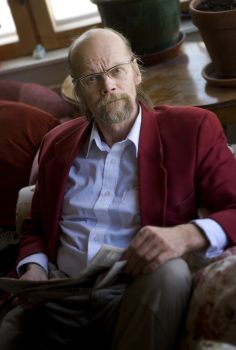

Risto Ahti. Kuva: Harri Hinkka

Poems from Narkissos talvella (‘Narcissus in winter’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Risto Ahti (born 1943) published his first work in 1975. His poetic expression finds form remarkably often in prose poems, and Narkissos talvella is made up exclusively of these. His poems transmute language into a mystical, surreal world, sometimes enigmatic and subjective in the extreme, and at its best strangely suggestive. It is as if Ahti’s world were in a state of constant change, subjected to a relentless process of demolition and rebuilding. The experience of the individual, generally his encounter with truth, is central to many of Ahti’s poems; the inner reality of a person manifests itself as more essential than the outward appearance. Ahti’s poems exhibit a fruitful contradiction: on the one hand, the accuracy with which he uses words and, on the other, the continual shape-changing and lack of definite boundaries of the world they describe. More…

Patsy, the artist of the lumber camps

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Atomintutkija ja muita juttuja (1950). Introduction by Aarne Kinnunen

Deep in the wilds, where the only sound is the sad, primeval sighing of the forest, it is easy to succumb to a mood of boredom and melancholy. It may sometimes occur to you that in such a place you are wasting your life. Real life goes on elsewhere, in places with more people, more signs of human activity, more light, more gaiety…

You fell a tree, severing a string of that mighty instrument, the forest. You saw it into logs, you strip off the bark: it all seems dull and pointless. Sometimes the rain decides to go on for days: the trees have streaming colds, droplets hang from every needle-tip. You make for the shelter of a lumber camp. But the low-roofed rest-hut, deep in the forest, looks a dreary place, the well-known faces are so dull, the talk so futile. You feel you know in advance what each man is going to say. And the food, too, is just the same as usual, the same old rubbishy mush. The sight of the pot, with its blackened sides, gives no pleasure: you know all too well what is in it. And those grubby playing-cards, how disgusting! The mere sight of them is enough to make you feel defiled… More…

The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Puhalluskukkapoika ja taivaankorjaaja (‘The blow-flower boy and the heaven-fixer’, 1983). Interview by Olavi Jama

Cold.

A chill west wind came over the blue ice. It went right to the skin through woollen clothes. Shivers ran up and down the spine, made shoulders shake.

In the bank of clouds close to the horizon, right where the icebreaker had crunched open a passage to the shore, hung a pale blotch, a substitute for the sun. It gave off more chill than warmth.

Lennu’s teeth were chattering.

He wore a buttoned-up windbreaker, a hand-me-down from Gunnar, over a heavy lambswool shirt. It couldn’t keep off the cold. More…

The report

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

A short story from Kesä ja keski-ikäinen nainen (‘Summer and the middle-aged woman’) Introduction by Margareta N. Deschner

Dear Colleague,

First of all, I want to thank you and your wife for the pleasant evening I and my wife had in your summer villa in August. Briitta (since we are old acquaintances: with two i’s and two t’s, remember?) especially wants me to mention that she will never forget the half moon climbing the hill behind your sauna, surprising us with its speed. The next time we looked it was half-way up the sky! Without doubt, your fine tequila had something to do with the matter, one shouldn’t forget that. Even so, it was quite a show, just like the time a bunch of us guys had gone skiing and you bragged that you had arranged for the barn to catch fire. I hope that you and your wife – I mean Alli – will be able to visit us next winter and taste a superb Mallorca red wine called Comas, which we brought home. It is by far the best red I have ever tasted and indecently cheap to boot. I hope you will come soon. The wine won’t keep indefinitely, as you well know. We’ll save it for you. So thanks again.

Poems

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

The poems of Aleksis Kivi were long considered no more than a peripheral aspect of his work. They were, as Kivi’s friend Kaarlo Bergbom wrote in a review, ‘gold that can’t be minted into coins’. The reason appears to have been Kivi’s poetic technique, which made a clear break with tradition. He did away almost completely with rhyme and instead emphasised the rhythm and musical sound qualities of words. He shortened words in a way that did not find favour with any subsequent Finnish poets. He avoided emotional expressions of patriotism and romantic love poetry; instead, he composed poems that were extended, narrative and fresco-like. Lauri Viljanen, whose 1953 study brought about a re-evaluation of Kivi’s poetry, has given them the apt soubriquet ‘epic idyll’.

The first of Kivi’s poems appeared in the Kirjallinen Kuukauslehti (‘Literary monthly magazine’) in 1866; a collection of his poetry entitled Kanervala was published the same year. Other poems appear in his novels and plays, and some have appeared in a collection after his death. Karhunpyynti (‘The bear hunt’) is from Kanervala. Its descriptive nature is typical of Kivi. The verse structure is tightly controlled but unrhyming. The winter landscape of the third verse, repeated at the end of the poem, is a ceremonious point of rest among the otherwise busy activity.

– Kai Laitinen

![]()

The Bear Hunt

The men on skis set out for the forest, a brave company

With guns and bright spears

And clamouring dogs on the leash,

With blazing eyes,

As the dawn chases gloomy Night

From the sky’s brow,

And the sun raises his head. More…

Poems

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

Interview by Philip Binham

Birdmount

I hear a happy tale, it makes me sad:

no-one will remember me for long.

I will send a letter with nothing inside, the emptiness will reek

as the pines do, of fruit-peel and of smoke,

a scent only.

Here I have stayed a week, seven riverside days.

The river treads the mill, ah, treads the mill,

the river’s wide, this is a placid reach, the sky is near:

smoke, like the shadow of a birdflock passing, nothing else.

And now it is September:

there are more pine trees here, and more darkness too. More…

The power game

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Puhua, vastata, opettaa (‘Speak, answer, teach’, 1972) could be called a collection of aphorisms or poems; the pieces resemble prose in having a connected plot, but they certainly are not narrative prose. Ikuisen rauhan aika (‘A time of eternal peace’, 1981) continues this approach. The title alludes ironically to Kant’s Zum Ewigen Frieden, mentioned in the text; ‘eternal peace’ is funereal for Haavikko.

In his ‘aphorisms’ Haavikko is discovering new methods of discourse for his abiding preoccupation: the power game. All organizations, he thinks, observe the rules of this sport – states, armies, businesses, churches. Any powerful institution wages war in its own way, applying the ruthless military code to autonomous survival, control, aggrandizement, and still more power. No morality – the question is: who wins? ‘I often entertain myself by translating historical events into the jargon of business management, or business promotion into war.’

‘What is a goal for the organization is a crime for the individual.’ Is Haavikko an abysmal pessimist, a cynic? He would himself consider that cynicism is something else: a would-be credulous idealism, plucking out its own eyes, promoting evil through ignorance. As for reality, ‘the world – the world’s a chair that’s pulled from under you. No floor’, says Mr Östanskog in the eponymous play. Reading out the rules of a mindless and cruel sport, without frills, softening qualifications, or groundless hopes, Haavikko is in the tradition of those moralists of the Middle Ages, who wrote tracts denouncing the perversity and madness of ‘the world’ – which is ‘full of work-of-art-resembling works of art, in various colours, book-resembling texts, people-resembling people’.

Kai Laitinen

Speak, answer, teach

When people begin to desire equal rights, fair shares, the right to decide for themselves, to choose

one cannot tell them: You are asking for goods that cannot be made.

One cannot say that when they are manufactured they vanish, and when they are increased they decrease all the time. More…

Hotel for the living

Issue 2/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from Hotelli eläville (‘Hotel for the living’, 1983). Introduction by Markku Huotari

Raisa and Pertti are a married couple with three children, Katrielina, Aripertti and Artomikko. When she discovers she is to have another, whom she names Katjaraisa, Raisa decides to have an abortion, because another child, even if welcome, would now jeopardise her career – she has been offered a job with an international company at the very top of the advertising world. Raisa is the successful entrepreneur of the novel – on the one hand coldly calculating, without feeling, on the other superficially sentimental, perhaps the most startlingly ironic of the characters in Jalonen’s novel. His image of the brave new woman?

During her lunch hour Raisa took a walk via the laboratory, asked reception for the envelope and thrust it unregarded into her handbag. She was aware of her already knowing, but short of the envelope, there would as yet be no restrictions, nor were there any decisions that would have to be made. She had called Tom Eriksson, discussed yet again the same points and particulars, and ended tracing a finger over the two beautiful pictures on her wall. ‘The loveliest of seas has yet to be sailed’ and ‘I am life! For Life’s sake.’

She thought of Katjaraisa, her features, the palms the breadth of two fingers, just as Katrielina’s had been, and the same button-eyed gazing look as Katrielina. More…

The Sleepwalker

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

We print here an extract from the radio play Somngångerskan (‘The sleepwalker’, 1978). Walentin Chorell himself said that he felt this genre to be the closest to his heart, and his radio plays are perhaps the element of his work that has contributed most to his reputation in Finland and in the rest of Europe.

As the play begins, we sense night in the old, rambling log house, with a clock ticking in the background; the sound comes closer, intensifies, and then dies away again. The clock strikes three; its works are old and complaining. Long silence.

Then the silence is broken by the loud and happy laughter of Jerine, the sleepwalker. A flock of gulls is heard calling over the beach; there is a gentle summer breeze, and the waves are lapping against the boulders on the shore.

FIRST VOICE (=the mother, frightened)

What’s wrong? What have you wakened me up for?

SECOND VOICE (=the father)

It’s Jerine. She was laughing in her sleep. More…

Mirdja

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

An extract from the novel Mirdja (1908). Introduction by Marja-Liisa Nevala

Now they were in the city – their minds more alive than usual with wilfulness and daring.

For – quite unable to jettison their shared life – they had at least to get on top it… Had to … Every single person has to battle …

And Mirdja’s head was full of efficacious rules for balance, countless cool and wise thoughts – to meet all conflicts.

Lucidly and coldly she had clarified her present position for herself. She was married. Right. No particular joy in that. But no need for any particular disaster in it either. And if she had thrown herself into dependence through this banal arrangement, the sort that everyone has a little of in this life, she had only herself to blame. She had to be able to live by rising above the trivialities of existence. Besides, she had always known that in the final count it was immaterial whom one was married to. A marriage always had its own profile, its dreary distinguishing marks, but one was not compelled to absorb these dreary sides into one’s own being. How did they do it in France? Every year thousands of marriages occur, without an atom of personal liking entering into the game, and extremely seldom are the marriages unhappy. Why so? Mutual politesse: a little of the art of social intercourse, and the whole problem is solved. In the morning a tiny friendly greeting at the breakfast table: ‘Bonjour ma chère,’ – ‘Bonjour, mon ami’; a courteous kiss on the hand, a pretty smile in response, and everything’s as it should be. Because those people know how to go about it. Marriage – one of society’s many empty regimentations! Only stupid people tried, within narrow limits like these, to find fullness of content or idealize. Stupid, Mirdja had been. Comically destructive in that heavy northern solemnity of hers – refusing to acknowledge any form without content, yet fearful of endowing content with any form except the conventional and time-tested. She had lived with a common-or-garden person’s longing for fullness, and then allowed, exactly like that sort of person, her disappointment and bitterness to flood over all her nearest and dearest. She had lived in indiscretion. She had been paltry and rotten and considered herself a slave … More…

Star-Eye

Issue 1/1984 | Archives online, Children's books, Fiction

A story from Läsning för barn (‘Reading for children’,1884). Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

There was once a little child lying in a snowdrift. Why? Because it had been lost.

It was Christmas Eve. The old Lapp was driving his sledge through the desolate mountains, and the old Lapp woman was following him. The snow sparkled, the Northern Lights were dancing, and the stars were shining brightly in the sky. The old Lapp thought this was a splendid journey and turned round to look for his wife who was alone in her little Lapp sledge, for the reindeer could not pull more than one person at a time. The woman was holding her little child in her arms. It was wrapped in a thick, soft reindeer skin, but it was difficult for the woman to drive a sledge properly with a child in her arms.

When they had reached the top of the mountain and were just starting off downhill, they came across a pack of wolves. It was a big pack, about forty or fifty of them, such as you often see in winter in Lapland when they are on the look-out for a reindeer. Now these wolves had not managed to catch any reindeer; they were howling with hunger and straight away began to pursue the old Lapp and his wife. More…

Mary Bloom

Issue 4/1983 | Archives online, Drama, Fiction

Introduction by Väinö Vainio

‘Is Mary Bloom about a revivalist religious meeting, a party political conference at which a new leader is born, or a rock concert? These are among the things that have been suggested. I don’t know. I don’t hope for restraint in the imaginations of those who choose.to interpret my work, although I observe it myself. The work of a writer is a part of life, it is an individual and collective experience that seeks, finds, takes and uses its materials like a motor machine. For those who create it the drama is real, as in the theatre, for the duration of the performance.’ Jussi Kylätasku

Characters

Mary Bloom

Martha, a doctor

Otto, a preacher

Disabled veteran

Serenity, his wife

Alcoholic

Cold Cal, a prisoner

Blind man, Deaf Wife More…