Author: Hildi Hawkins

Time to go

29 June 2015 | Greetings

[kml_flashembed publishmethod=”static” fversion=”8.0.0″ movie=”https://booksfromfinland.fi/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Books_Kesabanneri_2015.swf” width=”590″ height=”240″ targetclass=”flashmovie”]  [/kml_flashembed]

[/kml_flashembed]

Animation: Joonas Väänänen

We’ve often thought of editing Books from Finland as being a bit like throwing a party.

It’s our job to find a place to hold it, send out the invitations and provide the food and drink.

It’s your job to show up and enjoy.

![]()

Books from Finland is a party that’s been running since 1967 – for nearly fifty years.

In that time, we’ve served up almost 10,000 printed pages and 1,500 posts, a wide-ranging menu of the best Finnish fiction, non-fiction, plays and drama, accompanied by essays, articles, interviews and reviews.

We’ve had a ball, and to judge by the letters and emails we’ve received from many of you, you’ve had a good time too.

But now it’s time to go: the landlord, to stretch the metaphor, has called in the lease on our party venue. Faced with funding cuts in the budget of FILI – the Finnish Literature Exchange, which has since 2003 been Books from Finland’s home – the Finnish Literature Society has decided to cease publication of Books from Finland with effect 1 July 2015. Our archive will remain online at this address, and the digitisation project will continue. We won’t be adding any new material, though; this is, literally, the last post.

![]()

The party may be over, the lights and music turned off – but what about the partygoers?

They are doing what partygoers always do: they – we – are moving on.

Readers and writers, photographers and illustrators, everyone who’s helped, supported and enjoyed Books from Finland, thank you!

So long. See you around.

Hildi Hawkins & Leena Lahti

In memoriam Veijo Meri 1928-2015

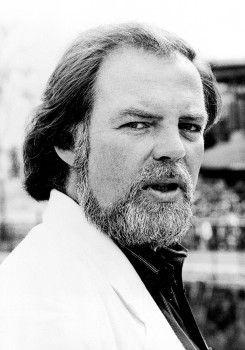

29 June 2015 | In the news

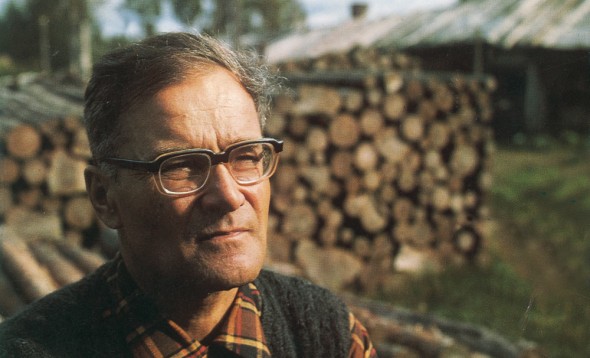

Veijo Meri. Photo: Irmeli Jung / Otava.

The writer Veijo Meri died on 21 June after a long illness.

Best-known for his war fiction, Meri was one of the towering figures of Finnish literature in the second half of the 20th century. Born in Viipuri in eastern Finland, subsequently ceded to the Soviet Union, he wrote novels, short stories, poetry, stage and radio plays and essays.

He came to prominence with his novel Manillaköysi (‘The manila rope’, 1957), which tells the tragicomic story of a soldier who tries to smuggle a rope home from the front during the Second World War. War and the army were central subjects for this anti-war writer, who deals with his subject with caustic humour, often focussing on loneliness, anxiety and sexual pressures.

A fresh voice in Finnish prose, breaking with its realist tradition, Meri was a film buff who used rapid changes of angle, compression and close-up to emphasise the strangeness and inexplicability of what he wrote about. His is manly prose, much admired by high-achieving male readers. Among the work we have published in Books from Finland is Underage, a short story that brilliantly illustrates Meri’s terse, masculine style; it is accompanied by an interview by Maija Alftan and Meri’s own essay on the art of the short story.

Meri’s minimalist style has something in common with American authors such as Ernest Hemingway and Raymond Chandler, and with the film-makers Sergei Eisenstein, Charlie Chaplin and Ingmar Bergman.

A prodigious talker and reader as well as a writer, Meri was very much at home in his skin. ‘You tend to avoid thinking about death,’ he wrote at the onset of middle age, because it seems a pity that you will have to leave the world, now that you finally feel at home here.’

Meri’s work has been translated into 24 languages.

New from the archive

29 June 2015 | This 'n' that

Mirkka Rekola. Photo: Elina Laukkarinen/WSOY

Enigmatic stories, poems and aphorisms by Mirkka Rekola

This week, poems and aphoristic short stories by Mirkka Rekola (1931-2015).

Rekola, as the long-time Books from Finland translator Herbert Lomas put it, was ‘a minimalist before minimalism was invented’. Amazingly enough, her sparklingly terse writing was considered ‘difficult’, and she had to wait until the 1990s before her work was widely read.

Rekola produced her first collection, Vedessä palaa (‘Burning water’) in 1954, making the cardinal mistake of choosing as publisher the conservative WSOY rather than the avant-garde Otava. The book received mixed reviews; as she said, ‘for readers of traditional verse I was completely unfamiliar, while for ultra-modernists I was not modern enough.’

All the work we revisit here shows the extraordinary vividness, accuracy and exuberance of her writing – both in the poems and the often ruefully funny short stories called ‘Mickeys’.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 402 articles and book excerpts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Lovely black eyes

23 June 2015 | This 'n' that

Agony uncle?: Jean Sibelius during his travels in Germany, in 1889

Jean Sibelius on how to keep your mojo

The main music critic of Päivälehti (‘The daily newspaper’) in the 1890s was the celebrated composer Oskar Merikanto, writes Vesa Sirén in Päivälehti’s successor, Helsingin Sanomat. Often, but not always, Merikanto praised first performances of works by the yet more stellar Jean Sibelius.

June 1895, however, saw the publication of Merikanto’s I sommarkväll (‘Waltz for a summer’s night’). ‘Tomorrow’s Päivälehti should have a review by Sibelius!’ wrote an excited Merikanto.

The short review duly appeared the following day, attributed not directly to Sibelius but to ‘a certain prominent composer’. In it, Sibelius hints that its uses may be more than strictly musical:

This waltz is extraordinarily pleasant and clever in both form and content. The introduction immediately reveals the composer’s intentions. This waltz contains an extraordinary passion. It is like our sky, which seems so grey, but which reflects that grey light that is born in black eyes when one is with one’s beloved. Everyone should buy it, for it is the shortest route to acceptance by one’s beloved and to one’s true desires.

New from the archive

23 June 2015 | This 'n' that

Kalle Päätalo. Photo: Gummerus.

This week, Kalle Päätalo – once Finland’s most successful author

Author Kalle Päätalo (1919-2000) was a rare bird in the book-publishing world. Beginning in 1962, his series of autobiographical novels Juuret Iijoen törmässä (‘Roots on the banks of the Iijoki river’) were published annually in editions of 100,000 copies. At a cautious estimate, one million Finns out of a total population of five million read Päätalo. He was a unique phenomenon, and, for his publishers, a highly lucrative one.

Despite his popularity, this former forestry worker and builder never achieved critical acclaim; the literary establishment remained cool towards him. What was the secret of his enormous appeal? By 1987, when we published this week’s extracts, the way of life Päätalo was chronicling was fast disappearing; he portrayed of the living and working conditions of the far north and the rich dialect of the region with a near-anthropological accuracy. Päätalo’s autobiography was almost coterminous in scope with the existence of independent Finland, and his depiction of the ruggedly individual characters of the north was at the same time a celebration of national values.

In this excerpt, from Tammerkosken sillalla (‘On Tammerkoski bridge’, 1982), the narrator’s excitement as he finds Martin Eden by Jack London – along with the Finnish author Mika Waltari, one of Päätalo’s great writer-heroes – in the local library is palpable. And many of his readers would have remembered the difficulties of living in small apartments at close quarters with other family members, in this case a less-than-congenial mother-in-law: ‘My cock cowered among my pubic hair like a guilty prankster after a practical joke…’.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 400 articles and book excerpts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Dracula fights for Finland

16 June 2015 | This 'n' that

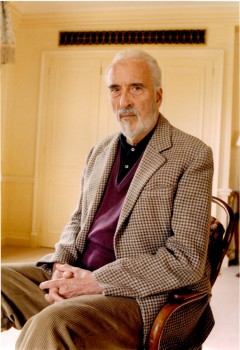

Christopher Lee. Photo: Devlin crow / CC BY-SA 3.0

Actor Christopher Lee loved Finland and knew the Kalevala

Among the obituaries of Christopher Lee, the celebrated actor who died last week at the age of 93, one fact has remained strangely overlooked: his connection with Finland.

Lee (born 1922) specialised in monsters and villains; his most famous roles included Dracula, the Mummy, Frankenstein’s monster, Count Dooku in Star Wars and the wizard Saruman in The Lord of the Rings.

Writing in the Helsingin Sanomat newspaper, Veli-Pekka Lehtonen reveals that Lee knew Finland well. As a very young man he had volunteered for service in the Winter War of 1939; the British soldiers’ skiing skills, however, made them less than useful and they were sent home.

Lee also had an extensive knowledge of the architecture of Helsinki, and loved the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala.

That love came full circle in his role in The Lord of the Rings. J.R.R. Tolkien, the trilogy’s author, was also a Kalevala fan – the inspiration for his work on the kingdom of Middle Earth lay in the Kalevala’s story of Kullervo. As he wrote to his friend, the poet W.H. Auden, in 1955, ‘the beginning of the legendarium… was an attempt to reorganise some of the Kalevala, especially the tale of Kullervo the hapless, into a form of my own.’

Tolkien, a professional philologist, particularly loved the Finnish language. He described finding a Finnish grammar book as being like ‘entering a completely new wine-cellar filled with bottles for an amazing wine of a kind a flavour never tasted before.’

Christopher Lee may not have known Finnish, but he had clearly sampled the same wine.

Angels and devils

11 June 2015 | This 'n' that

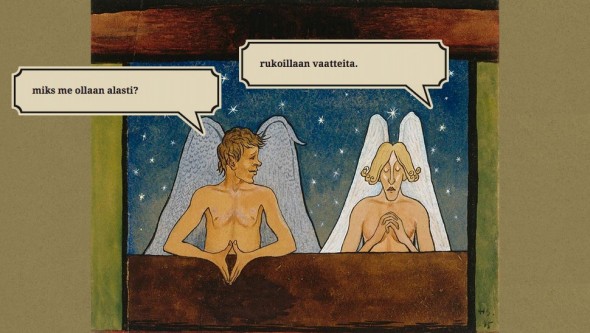

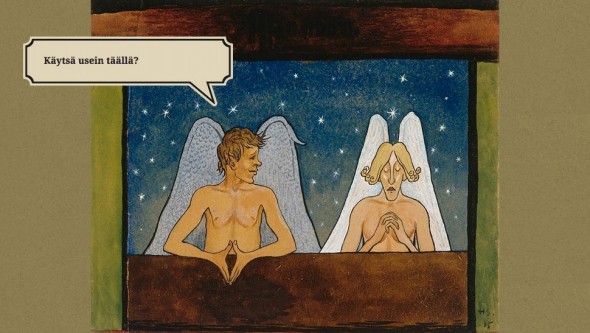

A new website explores the work of artist Hugo Simberg

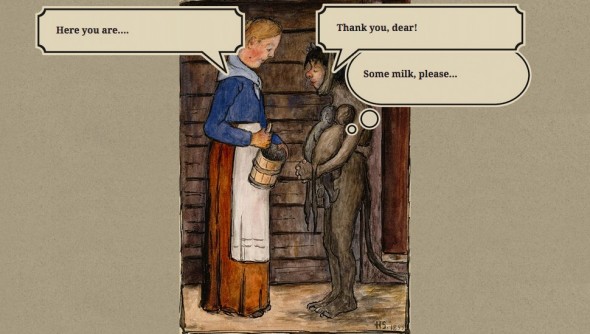

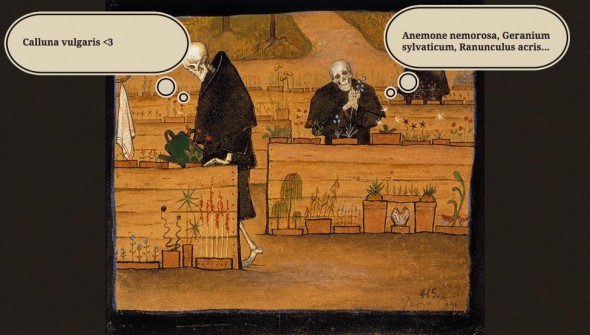

Two small boys carry a wounded angel; a farmer’s wife gives milk to a little devil and her twins; skeletons tend the plants in the Garden of Death. The mythical figures that populate the paintings of the symbolist artist Hugo Simberg (1873-1917) have a wayward and macabre charm that is all their own.

The Helsinki Ateneum Art Museum’s new website, The Other World of Hugo Simberg, offers an opportunity to explore Simberg’s life and work. Showcasing twelve of his best-known paintings, it lays a trail through associated visual and textual material – different versions of the works, photographs, sketches, letters….

If you’ve ever wondered what Simberg’s characters might be thinking or saying, the website also gives you the opportunity to provide thought or speech bubbles, which can then be uploaded to the website.

Angelic meetings: ‘Why are we naked?’ ‘Let’s pray for clothes!’ (above); ‘Do you come here often?’ (below).

New from the archive

11 June 2015 | This 'n' that

Helvi Hämäläinen. Photo: Literary Archives of the Finnish Literature Society.

This week, an excerpt from Helvi Hämäläinen’s gorgeously sensuous novel Säädyllinen murhenäytelmä (‘A respectable tragedy’,1941)

Right at the top of the list of untranslated Finnish masterpieces, for me, is Helvi Hämäläinen’s monumental Säädyllinen murhenäytelmä.

Written in the fateful summer of 1939, as the world waited for war, this story of love among the Helsinki intelligentsia is at the same time both a roman a clef – it caused a sensation on publication as the real people behind the fictional characters were recognised – and a vivid picture of its age. The falling cadences of its luxuriantly proliferating phrases offer a voluptuously aesthetic poetry of the senses as they slowly tell the story of love lost and then, gradually, regained. And the book answers the question, what was it like to be alive then?, with incomparable vividness. In this extract, the novelty of apartment living in the 1930s, the colours and smells, the new social habits, are all brought to life with extraordinary intensity.

We also republish a selection of poems published much later in Hämäläinen’s life, many of them impassioned elegies for the lives lost in the Second World War, giving voice to the sheer weight of sorrow, of grief for those who were lost.

If you’d like to read more, Soila Lehtonen’s evocative essay on Säädyllinen murhenäytelmä accompanies another excerpt; while a glimpse of its sequel, Kadotettu puutarha, (‘The lost garden’, 1995), follows the story onward to an elegiac description of the parts of Karelia that were ceded to the Soviet Union in the Second World War.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 396 articles and book excerpts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

New from the archive

8 June 2015 | This 'n' that

F.E. Sillanpää in his home receives the news that he has been awarded with the Nobel prize in literature in 1939.

This week, a short story from Finland’s one and only Nobel laureate, F.E. Sillanpää

Time has largely forgotten Frans Emil Sillanpää (1888-1964), but in the interwar years of the last century this complex writer – biologist, realist, mystic and proponent of ‘life-worship’ – was one of the most prominent in Finland. His work, intriguingly archaic and modern at the same time, is well represented by Järvi (‘The lake’, 1915), the short story we publish here.

Finland’s only Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded, perhaps not coincidentally, in the fateful year of 1939, and when Sillanpää travelled to Stockholm to receive his award, the Soviet Union had already attacked Finland. After the award ceremony, Sillanpää stayed in Sweden to raise funds for his beleaguered country.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 393 articles and book extracts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Oldest Helsinki photograph

2 June 2015 | This 'n' that

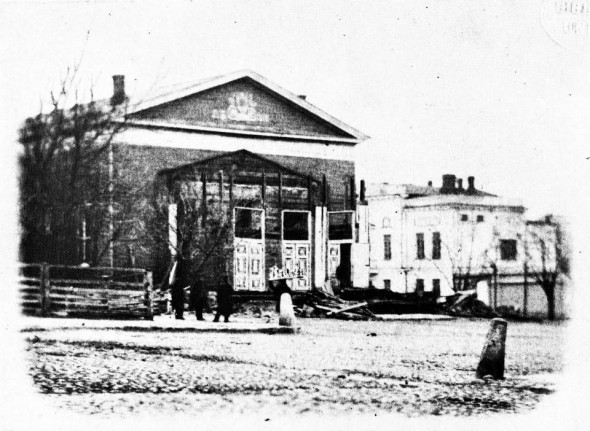

Old Helsinki: this image, taken in the Esplanadi park more than 150 years ago, shows the old theatre building, which was demolished in the 1850s. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Hidden in plain sight in Sven Hirn’s Kameran edestä ja takaa – valokuvaus ja valokuvaajat Suomessa 1839-1870 (‘Behind the camera and in front of it – photographs and photographers in Finland 1839-1870’), published more than 40 years ago, the image shows four men standing in front to the theatre designed by Carl Ludvig Engel in 1827 (and demolished when it became too small to accommodate the city’s enthusiastic theatre-going public in the 1850s). Unusually, in those days of slow shutter speeds, the photograph shows people, among them Carl Robert Mannerheim, father of the Marshal Mannerheim who was to lead Finland’s defence forces in the Second World War (third from left).

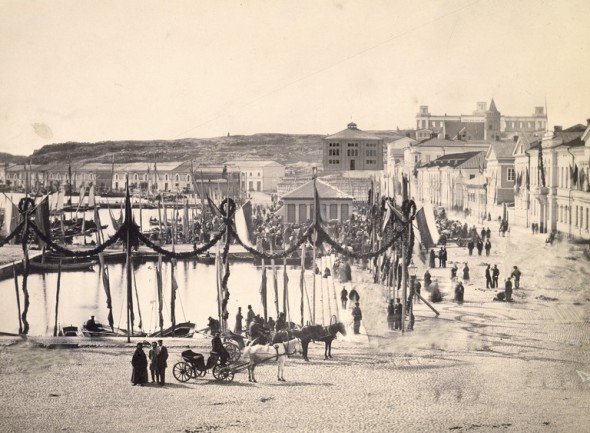

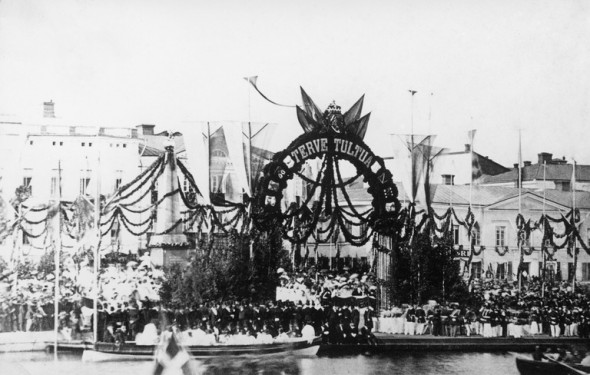

Among the other photographs published by Helsingin Sanomat are some images of Helsinki decked out in garlands awaiting the arrival of Tsar Alexander II to the capital of his autonomous grand duchy of Finland in July 1863.

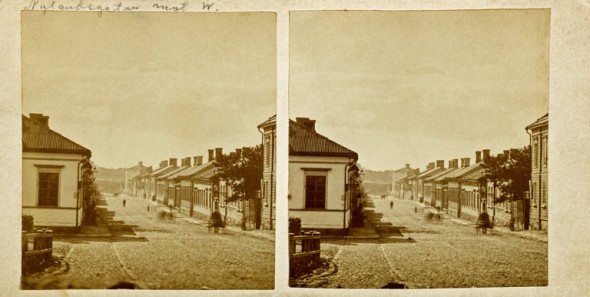

Other mid-century images show central Helsinki looking not unlike its present-day self. It’s only when the camera ventures outside the few blocks of the city centre that the view becomes more unfamiliar, the streets lined with one- and two-storey wooden houses.

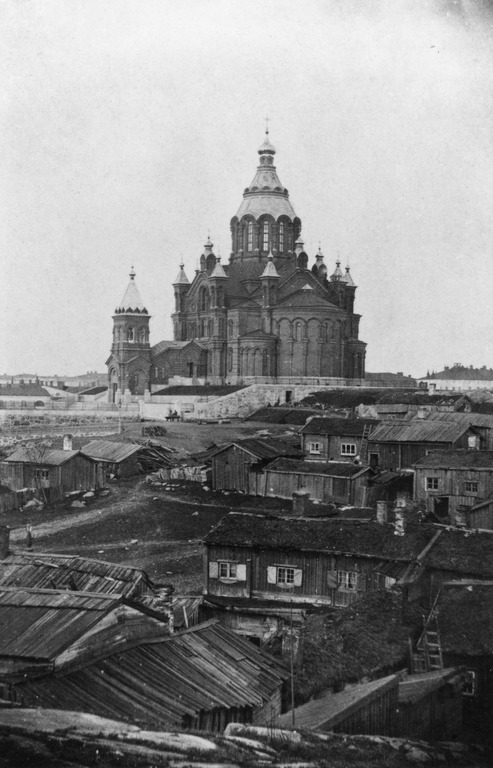

Most intriguing of all, however is a sequence of eighteen photographs taken in 1866 by one Eugen Hoffers from the top of Helsinki Cathedral. Helsingin Sanomat has linked them into a panorama with views of Suomenlinna fortress, the new Russian Orthodox Uspenski Cathedral, Books from Finland’s old publisher Helsinki University Library, and the burgeoning city beyond.

Imperial welcome: Helsinki is bedecked with flowers to welcome Tsar Alexander II on 28 July 1863. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Pomp and circumstance: elaborate floral tributes for the visit of Tsar Alexander II in 1863. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

New and old: the recently completed Uspenski Cathedral is surrounded by a shanty-town of tumbledown cottages in this image from 1868. Photo: Hoffers Eugen, Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

Strange and familiar: this picture, from 1865, shows the Cathedral, the Senate and the University Library surrounded by low wooden buildings and unbuilt land. Photo: Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

City of wood: beyond the familiar buildings of the few blocks of the then city centre, in this image from the 1860s, lie streets of modest one- and two-storey wooden houses. Photo: Gustaf Edvard Hultin , Helsinki City Museum / CC BY-ND 4.0.

For your eyes only

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Photo: Steven Guzzardi / CC BY-ND 2.0

Imagine this: you’re a true bibiophile, with a passion for foreign literature (not too hard a challenge, surely, for readers of Books from Finland,…). You adore the work of a particular writer but have come to the end of their work in translation. You know there’s a lot more, but it just isn’t available in any language you can read. What do you do?

That was the problem that confronted Cristina Bettancourt. A big fan of the work of Antti Tuuri, she had devoured all his work that was available in translation: ‘It has everything,’ she says, ‘Depth, style, humanity and humour.’

Through Tuuri’s publisher, Otava, she laid her hands on a list of all the Tuuri titles that had been translated. It was a long list – his work has been translated into more than 24 languages. She read everything she could. And when she had finished, the thought occurred to her: why not commission a translation of her very own? More…

New from the archives

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Juhani Peltonen. Photo: C-G Hagström / WSOY.

This week’s pick is, like last week’s, a period piece – this time a cry for help from the 1980s in the work of Juhani Peltonen (1941-1998).

Like Runar Schildt’s short story Raketen, written shortly before Finland gained independence from Russia and was almost immediately plunged into civil war, these pieces by the multitalented Juhani Peltonen, who wrote plays for stage and radio as well as short stories, novels and poems, were published shortly before major and irrevocable change.

In the short story ‘The Blinking Doll’, we are a year short of the fall of the Berlin Wall, and it seems as if things are never going to change. We follow two forty-year-old lawyers, Juutinen and Multikka, as they trudge along the beach in one of the charming resort towns of the west coast in which they have spent a couple of days dealing with a minor felony case.

They’re both forty, and divorced, disillusioned with their jobs and with the world; and both are infatuated with one of their colleagues, a woman whom they call ‘The Blinking Doll’.

There is, Peltonen says, a ‘pact of friendship and mutual assistance between the men’ – a jocular reference to the notorious treaty of 1948 in which Finland was obliged to resist attacks on the Soviet Union through its territory, and to ask for Soviet aid if necessary. In 1988, this seemed as if it were written in stone – and the men’s emotional lives are similarly petrified. They discuss their isolation, their lack of purpose, their inexplicable weeping fits. The most painful thing, says Multikka, is love; or, says Juutinen, and which comes to the same thing, the lack of it.

As Erkka Lehtola, our then Editor-in-Chief, remarks in his introduction, Peltonen – Finnish literature’s best-known comi-tragedian, he calls him – focuses on the difficulty of loving in a violent, mechanical, oppressed world. Is it the passage of twenty-five years that imbues his writing with such a poignant sense of stasis and futility? There is a sense of desperation, barely controlled. As one of his poems has it,

Too abundant in the course of the evening

Cries for help from the heart of stifled detail, legato.

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 388 articles and book extracts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

New from the archives

11 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Sinikka Tirkkonen. Photo: Otava.

Short short prose from Sinikka Tirkkonen

This week, a short story by Sinikka Tirkkonen (born 1954), which we published in 1988 – a piece of confessional prose, ‘comfortless and depressed’, as Tero Liukkonen’s introduction has it, about life in a bleakly solipsistic world; the kind of writing, one’s inclined to say with hindsight, that only the young, or at least the not very old, have the leisure to produce.

‘Things are only right for me,’ says the unnamed narrator, ‘when they bring grief and distress in their train, when they pile up guilt feelings, harsh self-criticism and self-denial… All my life I’ll be deprived of something, always – full of cares, fears, terrible agonies. I’ve no right to live.’ There’s a train journey north, two women in a car on a long drive across Lapland, work, a husband’s unfaithfulness, pointlessness….

It’s beautifully done, though, with an appealing poetic minimalism. Enjoy!

![]()

The Books from Finland digitisation project continues, with a total of 388 articles and book extracts made available on our website so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Images of war

5 May 2015 | This 'n' that

A soldier playing his accordion. Photo: SA-kuva

Between 1939 and 1944 Finland fought not one, but three separate wars – the Winter War (1939-45), the Continuation War (1941-44) and the Lapland War (1944-45).

We have become used to black-and-white images of the conflict, with their distancing effect. Among the 160,000 images in the Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive, however, are some 800 rare colour photographs from the Continuation War, which bring the realities of fighting much closer. The events pictured leap out of history and into the present. More…

New from the archives

5 May 2015 | This 'n' that

Runar Schildt

It’s a period that seems sometimes to have disappeared from view – Helsinki in the final years of Russian rule – but Runar Schildt’s short story brings it vividly to life. The characters – Sahlberg the baker and his mortal enemy, Johansson from the customs service; the restaurant-owner Durdin and Elsa, daughter of a commissionaire at the Senate, around whom the story revolves – spend a lazy but sexually charged summer Sunday in their villas just outside Helsinki, their hidden emotions all too familiar to those of a later age…

As the story’s translator, the formidably erudite George C. Schoolfield, remarks in his introduction, Runar Schildt (1888-1925) has often been hailed as a Finland-Swedish classic. There’s a quality of aesthetic decadence in his work that makes him very much a product of his time. There’s nothing, in Raketen, with its solid, belle epoque atmosphere, to foreshadow the change that was so soon to engulf Finland, with the granting of independence in 1917 and the bitter civil war that followed. Schildt was in Helsinki during the months when it was ruled by the Red side in the civil war; afterwards, he served as a clerk in the terrible detention camp for Red prisoners of war on Suomenlinna island. It was a new world, in which all the old certainties were questioned. Timid, conservative and something of a dandy (his friend Hans Ruin said he always looked as if he had stepped out of a bandbox), Schildt may well have felt out of tune with the times. By 1920 he had ceased to write the prose at which he excelled, and had turned to drama, with which he had much less success.

Schildt shot himself, in 1925, in the courtyard of the old university clinic in Helsinki. He was not yet 40.