In the beginning was… DNA?

8 October 2010 | Reviews

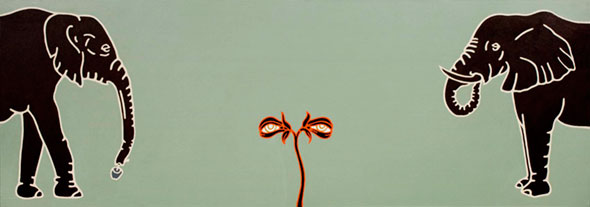

Adam and Eve, or the elephants: Osmo Rauhala’s sketch of The Fall of Man. As the bull eats the apple, evil rises from the ground in the form of a plant with eyes: a ‘misbreed’, a cross of two species alien to each other

Kuutti Lavonen – Osmo Rauhala – Pirjo Silveri

Tyrvään Pyhän Olavin kirkko – sata ja yksi kuvaa /

St Olaf’s Church in Tyrvää – One Hundred and One Paintings

Toim. / Edited by Pirjo Silveri

Translations: Silja Kudel, Jüri Kokkonen

Helsinki: Kirjapaja, 2010. 143 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-247-103-1

€44.30, hardback

The old shingle roof of the early 16th-century stone church of St Olaf in Tyrvää, in the province of Pirkanmaa, southern Finland, was repaired by village volunteers in 1997. Three weeks after they completed their work, a drunken arsonist set the church on fire.

The 18th-century master painter Andreas Löfmark had decorated the wooden panels of the gallery with portraits of the Apostles, images of the Passion of Christ and a portrayal of the Last Judgement.

Valued as a treasure of national importance, the whole interior, including the Löfmark paintings and the newly repaired roof, vanished into thin air.

But the local community and its volunteers didn’t give up: six years later the wooden interior, hand-carved, was rebuilt. Architect Ulla Rahola was responsible for the design of the reconstruction work.

The parish board made a decision to commission new paintings, following figurative style of the the original pictorial scheme. The interior committee invited two eminent artists, Kuutti Lavonen and Osmo Rauhala, to join the project, working with a group of assistants. The materials had to be carefully researched and tested, as there is no heating in the stone church, and humidity and temperatures vary enormously.

It took the artists five years to finish the job: 101 panels were painted, 29 by Lavonen and 79 by Rauhala.

After the fire: following completion of the restoration with its hand-carved wooden fixtures, St Olaf was reconsecrated in 2003

Tyrvään Pyhän Olavin kirkko – sata ja yksi kuvaa/ St Olaf’s church in Tyrvää – One Hundred and One Paintings tells the story of the painstaking process of renovation.

When the artist Osmo Rauhala (born 1957) began planning his pictorial scheme for St Olaf, the Story of Creation and the birth of life, he found himself engaged in a dialogue with the contemporary world and the scientific explanation of life; his images ‘allude to the big bang theory (or the Creation of Light), the role of DNA and the creation of the animal kingdom. The theme of the pulpit, In the Beginning Was the Word, poses the question: might the first word have been DNA? I am not speculating as to who created DNA. Perhaps God created DNA as the first word.’

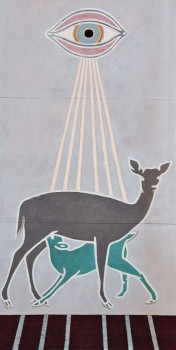

The sixth day by Osmo Rauhala: the beasts of the earth and the large mammals were created. The Birth of Milk (oil on wood, 60 x 30 cm)

The seven paintings in Rauhala’s the Story of Creation have a common motif: an eye. But after deciding not to include any human figures in his work, he found himself facing the problem of how to depict the appearance of humankind.

For the panel portraying the sixth day Rauhala painted a doe with her calf and called it The Birth of Milk, as ‘a deer is a mammal just like we are’. Rauhala is known for his paintings of animals – deer in particular.

According to him, modern science theorises precisely the same order as the book of Genesis: ‘first came water organisms and fish, then reptiles and birds and finally land-dwelling animals and mammals, with humans last of all.’

Rauhala chose to portray the Creation of Man on the Seventh Day by depicting wet human footprints, on a beach, suggesting the evolutionary transition from water to land: the first man pauses to stand on the sand and honour God’s day of rest.

The seventh day by Osmo Rauhala: Man stands on the beach, respecting God’s work (oil on wood, 60 x 30 cm)

The Fall of Man was another problem. The 18th-century church painter Mikael Toppelius had placed an elephant in his painting of the Fall in Haukipudas church. Rauhala sees the elephant as an intelligent creature, a denizen of Eden, and capable of using its trunk like a hand: ‘it is a biological fact that the cow elephant attracts the bull by offering fruit.’

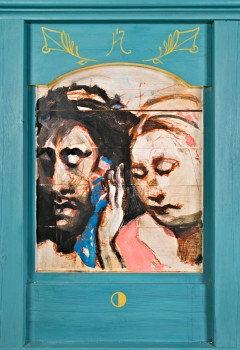

If Rauhala is an animal painter, the graphic artist and painter Kuutti Lavonen (born 1960) has gained his fame for his bold human (and angel) figures, faces in particular.

His method in St Olaf’s included sketching his compositions on the primed pine panels in red chalk. ‘I believe in the power of imagery. I use the cross motif as a contemporary artist does, more as a symbol than a concrete object. – The cross is a powerful symbol – so potent that its mere shadow makes an impact.’

Lavonen has long been drawing inspiration from the legends of the saints and the archangels. In St Olaf, however, there is only one panel depicting heavenly figures.

Lavonen’s colour scheme includes red and black; again a strong contrast to Rauhala’s muted colours. The turqoise base was made with the mixture of yellow ochre and Prussian blue and used throughout in the woodwork.

Both artists had the content of each painting approved by the supervising committee, mainly consisting of theologians and art historians, and Lavonen says that he and his colleague were given ‘a great amount of artistic freedom’. Rauhala’s elephants caused no disagreement.

The Last Judgement was the most difficult work for Lavonen to conceptualise – and it posed a serious challenge for the committee. Lavonen’s second sketch depicted a female figure holding a set of scales and a lily. Lavonen explained that this would make the viewer to consider justice, or grace: is it better to pass judgement or show mercy?

In medieval church art the Last Judgement is depicted as the moment of rebirth; the female figure was a topic of debate, too. In the third version and final painting there is a lily and a dove, symbolising the Holy Spirit, descending upon the scales, but not tipping them.

‘Man is not the measure of all things – we must see our rightful place in the ecosystem, which the lily represents as flora, the bird as fauna’, says Lavonen. ‘I wanted to include the plant and animal kingdoms…. Man is not the king of all creation, but equal with everything else.’

The sun also rises: Osmo Rauhala’s sun appears to ascend from the altar as the viewer approaches down the aisle

The handsome book gives the reader an informative and interesting acccount of this rare project of artistic creativity, both spiritual and physical commitment and willpower. The numerous photographs, as well as the carefully constructed layout by graphic designer Ville Heinonen introduce the project in its entirety.

For someone who is not able to assess these new works of sacred art from a religious point of view, Rauhala’s two-dimensional, serene paintings, untouched by signs of human suffering, appear to have a mythical, mystical and universal quality in their profoundly rich symbolism. Inspired by Italian Renaissance and Baroque painters (he is currently writing a thesis on Bernardo Cavallino), Lavonen seems to interpret this suffering through a deeply personal, emotional language of powerful contrasts, with colours of blood and tortured flesh.

An atmosphere restored: the resurrected form of St Olaf in 2009, complete with the artwork by Kuutti Lavonen and Osmo Rauhala

There certainly are impressive stories told in these pictures, for any visitor to this small, beautiful medieval church, with or without Christian faith.

From Catholic to Lutheran: St Olaf (1506–1516) was consecrated by the last Catholic bishop of Turku; it became a Lutheran church in the early 17th century

The extraordinary contrast created by the approaches of two very different artists makes the reader want to go and witness it – the beginning and the end – with his or her own eyes.

Tags: art, cultural history

3 comments:

9 October 2010 on 1:00 am

Thanks for sharing this story and artwork at your Website. It is wonderful that part of the Church’s artwork is now accessible online for people– even across the Atlantic Ocean like myself– to appreciate.

28 October 2010 on 7:12 pm

I am not a religious person but I would love to visit this church with its simplicity and freshness, and the clarity of its imagery. What a wonderful article!

23 November 2010 on 9:02 pm

Your article is very interesting. I was performing with a choir in this beautiful, small medieval church on May 15th this year. Beside wonderful sacred paintings the church space has wonderful acoustics. My choir’s pilgrimage was filmed and a DVD recording will be a result as well as a TV program later on.