Drama queen: on writing, and not writing, plays

14 June 2010 | Articles, Authors

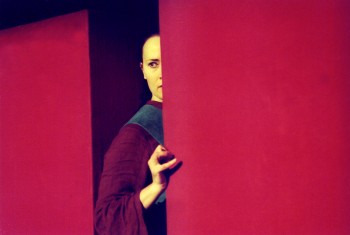

The queen who chose not to rule: Christina of Sweden in the play Queen C (first produced at the Finnish National Theatre in 2003, directed by the author, Laura Ruohonen, with Wanda Dubiel in the role of the Queen). Photo: Leena Klemelä

Extracts from ‘Postscript’, published in Kuningatar K ja muita näytelmiä (‘Queen C and other plays’, Otava, 2004)

It’s hard to read plays. I was bitterly disappointed at the age of eight, when I hid in my grandmother’s attic and opened up Romeo and Juliet, a book that seemed to promise lust and appalling acts. But it wasn’t even a real book; it was just talking from beginning to end! Where was the plot, the action, the much talked-about love story?

It’s also hard to write plays. Novels and works of poetry are closed miniature worlds that invite the reader in. A play always serves two masters. It has to be open and porous to allow the actor and the performance to penetrate into it.

For that reason, it’s more vulnerable, it can be more easily distorted into something unrecognisable than the sturdier forms of literature. If you want it to last, a play has to have a strong skeleton that can always be dressed in new clothes as time goes by to fit the fashion.

But it’s hard not to write plays, too. At its best, drama has a unique capability of transforming word into flesh: to evoke a world with many diverging ideas and opposing impulses expressed in vibrant, densely packed dialogue.

My way of writing a play is like an ancient Finnish bear hunt: you need to approach your prey from several directions at once, surround it circuitously, creep up on it sideways, get close to it without ever aiming directly at it. That’s how you have to approach your subject, prowling around it, approaching at a tangent, until you start to understand what’s in it that interests you and how that could form the basis of the work as you write.

![]() As a child I despised Queen Christina. In the story Tähtien turvatit (‘Protégés of the planets’) by Zachris Topelius [1872], she is portrayed as a spoiled princess who grows up to be a capricious traitor to her country, whose selfishness and vanity leads to the ruin of the nation and the death of great philosopher. When I grew up I started wondering what Christina was striving for when she gave up everything she had been born to: status, religion, gender. What made her abdicate her throne? To my surprise, in the broad field of literature written about Christina, I didn’t find a single satisfying explanation.

As a child I despised Queen Christina. In the story Tähtien turvatit (‘Protégés of the planets’) by Zachris Topelius [1872], she is portrayed as a spoiled princess who grows up to be a capricious traitor to her country, whose selfishness and vanity leads to the ruin of the nation and the death of great philosopher. When I grew up I started wondering what Christina was striving for when she gave up everything she had been born to: status, religion, gender. What made her abdicate her throne? To my surprise, in the broad field of literature written about Christina, I didn’t find a single satisfying explanation.

From Christina’s own writings a picture started to emerge of an ambitious rebel for whom the mere crown of little Sweden wasn’t enough. She wanted something more magnificent, and she wanted to acquire it by herself. At the beginning of Christina’s era, in the 17th century, an idea was emerging of the modern individual, someone who makes of herself what she wants to be. Centrally connected with this idea was an idealisation of personal freedom and independence. In my play Kuningatar K, Queen C, I wanted to examine a person who’s ultimate goal was freedom from all personal constraints, the most demanding of these being love, a person who was ready to go to any lengths to achieve her freedom.

As early as 1996 I wrote to a friend: ‘I plan to write a queen play. [The history plays by Shakespeare are called ‘king plays’ in Finnish.] The main characters are Queen Christina of Sweden-Finland and the philosopher Descartes, whose concept of love and equality will be one of the central themes of the play. [Descartes was invited to Stockholm in 1649, where he gave the Queen lessons in philosophy. He was said to have suffered from the harsh winter, fell ill, and died in February 1650. According to a new study, though, he may have been poisoned.] My aim will be to combine a poetic and comic-book style, with philosophical and spontaneously invented material, to create a play that will bring history almost too close and alive.’

But it was seven years before I finally got to direct Christina on the stage. Why? The most important reason can be seen in the structure of the text. I didn’t want to force historical themes that interested me into the disguise of drama, but I also didn’t want to give up my main character. Although the text loosely follows the events in the life of the historical Christina, it couldn’t advance by means of turns in the plot but instead by intertwining, multi-layered images and ideas.

The solution swam right to me. A Swedish field guide to fish fell into my hands – with recent research discoveries about the lives of eels. Modern natural science is still delightfully baffled when it comes to eels: the more we learn about them, the more mysterious they become. This primeval, mythical water creature, which is always changing its form and gender, was a door into Christina’s world for me. No matter how long the power of the entire modern scientific apparatus examines it, the riddle of the eel is never-ending. The same is true of Christina: the more I knew about her, the deeper the mystery. (Just a few years ago they dug up her grave for DNA analysis to make sure for the umpteenth time that she was a woman.) Among the aphorisms that the historic Christina wrote this one touched me most: ‘In every person there is a room to which only she has the key.’

Queen C in its present form, having been produced in various languages and as a radio play, is above all about the tensions that are fuelled by the pursuit of freedom, by power and the megalomania at the centre of power. Christina is a modern rebel who rejects the roles of woman, mother, and female ruler that are offered to her, and instead lets nothing get in the way of building a new identity that shatters concepts of gender and the limits of acceptability, regardless of the consequences. What happens to a person who places her own freedom above love, loyalty, and friendship?

Translated by Lola Rogers

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Laura Ruohonen

The gender of the soul - 14 June 2010

-

About the writer

Laura Ruohonen (born 1960) is a playwright, director and currently Professor of Dramaturgy at the Theatre Academy. Among her works are eight stage plays, film, radio and television scripts and two children’s poetry books. Her plays have been translated into ten languages and staged in a number of countries.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.