The unmaking of Finland’s forests

17 March 2010 | Reviews

Natural landscapes? According to Metsähallitus, the government body charged with forestry, ‘the regeneration area is defined according to topography, in accordance with the landscape. Retention trees and groups of trees are always left standing in regeneration areas to enhance the landscape and to improve the survival chances of species that require old and decaying trees.’

Ritva Kovalainen & Sanni Seppo

Metsänhoidollisia toimenpiteitä

[Silvicultural operations]

Helsinki: Hiilinielu tuotanto ja Miellotar, 2009. 200 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-99113-4-9

€ 43

Finns have a strong identity as forest people, partly because more than 95 per cent of them still speak an ancient hunter-gatherer language, Finnish, as their mother tongue. In spite of this cultural and historical background, Finland has become the world’s most eager and influential proponent of forestry models based on clear-cutting – felling all the trees in a particular area at one go and planting new trees to replace them.

In most parts of the world traditional forestry, practices have tended to emphasise selective logging, methods in which only some of the trees are removed at the same time. During the past four decades Finnish companies have often led the attack on such traditional forest management. Finland has produced the world’s largest forest consultancy company, Jaakko Pöyry, and some of the major paper and pulp corporations. Finnish companies manufacturing tree harvesters and the machinery for pulp and paper factories have also been world market leaders.

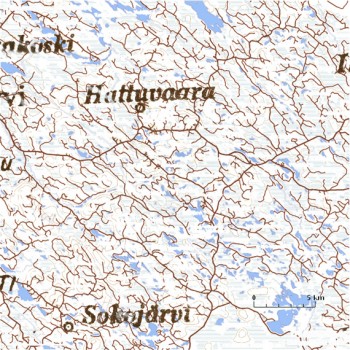

Three times round the globe: he road network built for forest harvesting is the densest in the world

The Finnish model of forestry has been hailed as an economic success story, but it has also caused large-scale devastation of natural forests and huge greenhouse gas emissions from forests, forest soils and peatlands in many different parts of the world, from Finland to Brazil and Indonesia.

Why have Finns, an ancient forest people, been so eager to export clear-cutting to other parts of the world?

The photographers Sanni Seppo and Ritva Kovalainen have produced two remarkable books tracing the roots of this strange paradox.

Puiden kansa (in English, Tree people, 1997; published also in German and Japanese), was an investigation of what we can still find out of the almost totally disappeared, ancient Finno-Ugric cultures, in which sacred trees and sacred forests played a prominent role.

Puiden kansa presented a number of intriguing and forgotten historical anecdotes. A thousand years ago, each Finnish household probably had its own sacrificial tree, and each village had a hiisi, a sacred burial forest. In 1228 the Pope of Rome gave an order to fell the sacred trees and forests of Finland. In spite of widespread resistance, the sacred forests were replaced by Christian churches, except in some parts of East Karelia and Northern Russia. Even in Finland some of the old sacrificial trees of individual households are still standing.

Roads for harvesters: 1200 square kilometres of land is trapped under 125,000 kilometres of road, permanently diminishing the forest area and preventing the forest from functioning as a carbon sink

Metsänhoidollisia toimenpiteitä (‘Silvicultural operations’, 2009), can be seen as a sequel to Puiden kansa. It describes how Finland’s present forestry-industrial complex was created, how the model was forced on the Finnish people, and how it has affected the lives of ordinary Finns at the grass-root level.

Finland was not occupied by the Soviet Union in the Second World War, and during the Cold War it was never a part of the Eastern Block. However, the organisational models that were adopted for the Finnish forestry sector after the Second World War should only have existed on the Soviet side of the border. As Sanni Seppo and Ritva Kovalainen point out, Finland’s forest-owners’ associations were organised by the state, but not to become free actors or genuine citizens’ interest groups. They were integrated into the state administration and controlled by it.

The Finnish state and the pulp and paper industries formed a tight alliance to push through a monolithic model of forestry, which had zero tolerance for dissenting opinion or alternative models. In practice the Finnish forest owners lost almost all control of how their own forests were to be managed. Everybody was forced to adopt the same practices, forest management procedures which were designed to guarantee an adequate supply of wood for the pulp and paper industries. The forest was first thinned to produce pulp wood and then finally clear-cut to produce pulp wood and timber.

Wilderness untouched: forester Jarno Hämäläinen has protected the five hectares of forest he inherited. ‘This is forest growing naturally, untouched by a human hand. This is a place of my own where I return to look for my roots, to listen to the humming of pine trees and the whining of mosquitoes.’

Forest owners who did not agree to clear-cut their forests were harshly punished by the authorities, and accused of ‘destroying their forests’ (!). This was, admittedly, an exceptional procedure in a Western democracy, but it did happen, and the stories included in Seppo and Kovalainen’s book reflect a clear and logical pattern. Seppo and Kovalainen have included an illuminating quote by one of the main architects of Finland’s new forestry policies, according to which ‘we would not have been as successful, if we hadn’t used an almost paramilitary organisation in the forestry sector’.

Puiden kansa was an optimistic book, a book full of hope. It concentrated on the small but wonderful fragments of the ancient world that still remain. This is one of the reasons the book has become so beloved by so many people in Finland. Metsänhoidollisia toimenpiteitä, on the other hand, is mainly about sadness and silent, repressed anger. Each square kilometre of an old forest consists of hundreds of different ‘places’, innumerable small spaces protected by the surrounding trees. When the forest is clear-cut, this rich mosaic of closed spaces disappears from the river of time, never to be regained within a human lifetime. A clear-cut forest becomes only one place, and often not a very attractive one.

Clear-cutting an old forest always is a small, localised end of the world for the people who live nearby and who used to love the forest as it was.

Through their pictures, Sanni Seppo and Ritva Kovalainen show what once was, and what remained after the logging. They show the people and the bright, hard grief shining on their faces. Moreover, they let the people speak and tell how it made them feel.

All the stories are different, but there are elements which are repeated, over and over again. First the fear that something is going to happen to the forest. A crucifying feeling of helplessness. Impotent anger. Shock, denial, depression, anxiety. Silent questioning of whether all the hatred is justified.

Seppo and Kovalainen’s writing is dense, sharp, deep. The words hit mercilessly, straight at the heart of painful, festering sores and complex dilemmas.

But it is still the photographs that really make the book. Statistics can lie, words can lie, even some photographs can lie, but if you see this collection, you will know in your heart that what you see is the truth about the matter, or at least an important part of the truth.

Tags: Finnish nature, industry, photography

No comments for this entry yet

Trackbacks/Pingbacks:

25 March 2010 on 1:53 am

[…] The unmaking of Finland’s forests: ‘the road network built for forest harvesting [in Finland[ is the densest in the […]

26 March 2010 on 2:50 pm

[…] Where’s the Densest Road Network in the World? Not where you’d expect: Rural Finland. More at Books from Finland, via the always reliable Things […]

3 November 2012 on 10:10 pm

[…] The unmaking of Finland’s forests – Books from Finland (tags: finland trees forest landscape) […]

10 August 2018 on 11:12 am

[…] The unmaking of Finland’s forests (2010) […]