Once upon a time

27 February 2014 | Children's books, Fiction

Stories from Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia (‘The giraffe mummy and other silly adults’, Teos, 2013), illustrated by Martina Matlovičová. Interview of Alexandra Salmela by Anna-Leena Ekroos

Stories from Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia (‘The giraffe mummy and other silly adults’, Teos, 2013), illustrated by Martina Matlovičová. Interview of Alexandra Salmela by Anna-Leena Ekroos

The monkey princess

Adalmiina’s life was not an easy one. Her parents decided to prepare her for her career as a princess when she was a little girl: when Adalmiina was three she was sent to ballet school, at four she started taking lute lessons and at five she went on a course in magic-mirror gazing.

When Adalmiina turned six, she received a giant suitcase full of princess clothes and shoes.

‘Put them on, darling, we want to see you in all your lovely beauty!’ her mother sparkled, waving a muslin veil.

‘I want to go to the jungle!’ Adalmiina demanded. ‘Without any clothes!’

‘Will we have to force you to dress in all your glory?’ her parents snapped.

‘You’ll have to catch me first!’ Adalmiina announced, running into the garden.

In the middle of the garden grew a spreading old oak. Adalmiina climbed into its branches. She jumped from branch to branch, sat down, swung her legs. When her exhausted parents dragged themselves under the tree with her heavy suitcase, Adalmiina swooped down to swing directly above their crowned heads.

In the middle of the garden grew a spreading old oak. Adalmiina climbed into its branches. She jumped from branch to branch, sat down, swung her legs. When her exhausted parents dragged themselves under the tree with her heavy suitcase, Adalmiina swooped down to swing directly above their crowned heads.

‘Your arms will stretch like a monkey’s,’ her mummy sobbed.

‘We’ll sell you to a circus,’ her daddy threatened.

‘I can’t wait,’ Adalmiina laughed, hanging head down from a branch, like a bat.

‘This is the end of your princessing. No decent prince is going to let a monkey like you into his castle. We can get rid of all your fine dresses and your lute and ballet studies,’ her parents lamented.

‘And the mirror course,’ Adalmiina reminded them. ‘And I’m allowed to climb trees.’

Her parents had to admit that Adalmiina made a much better monkey than she did a princess. And because they really cared about her, they set the grand suitcase under the tree as padding so that Adalmiina would not hurt herself if she accidentally fell or a branch were to break beneath her.

You have to take good care not only of princesses and children, but also little monkeys.

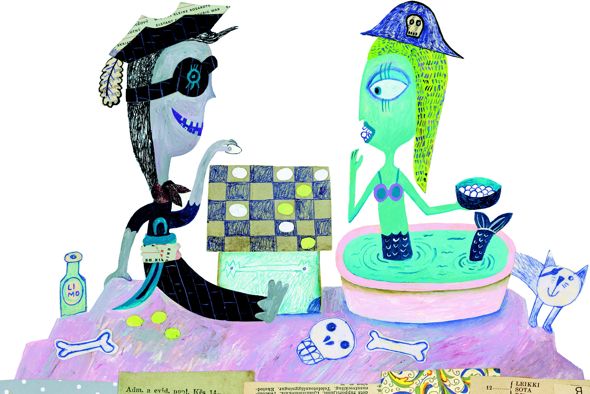

Pirate Mimmi

Mimmi’s parents were building a palace. They thought only about gates and towers, and not at all about Mimmi. So Mimmi escaped with the first people who happened to wander past her future family castle. Mum was busy decorating the kitchen while Dad was just setting up the family crest in the courtyard, so neither of them even tried to stop their daughter.

The passers-by were pirates. They gave Mimmi an eye-patch, a tricorn hat and a sword and took her with them to sail the seas.

Mimmi liked the pirate life; it was fun. It was exciting to swish her sword and roar like a lion, although sometimes you also had to loot a merchant galleon. Treasure, and counting treasure, soon got boring. But one day, in the hold of a captured ship, they found a chest which did not contain gold or crown jewels – curled up inside the small treasure chest was a little weeping mermaid.

Mimmi liked the pirate life; it was fun. It was exciting to swish her sword and roar like a lion, although sometimes you also had to loot a merchant galleon. Treasure, and counting treasure, soon got boring. But one day, in the hold of a captured ship, they found a chest which did not contain gold or crown jewels – curled up inside the small treasure chest was a little weeping mermaid.

‘How dreadful!’ exclaimed Mimmi, quickly freeing the mermaid.

She was so weak and dried-out that Mimmi had to take her to the pirate ship to recover. The mermaid sat in the washbasin, ate empowering pearls and played draughts with Mimmi with gold and silver coins. The girls became inseparable friends. When it was time for the mermaid to return to the sea, both of them became very sad.

Luckily the pirate captain found on the horizon with his telescope a desert island and gave it to the girls as a present. The pirates built a cabin there, standing half in the water and half on dry land, so that the two friends could live under the same roof.

Mimmi and the mermaid live there still. They fish, eat coconuts and pineapple and play with the monkeys. And when the pirates come to visit, all of them dance on the beach, roaring for joy like lions and the mermaid splashes in her washbasin.

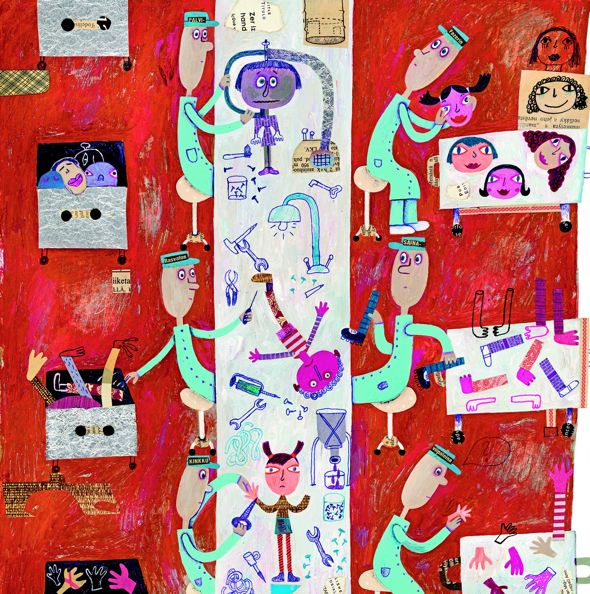

The Child Repair Shop

Sulo was not a very popular child. He did not get the main part in the school play. He did not win a single competition. And worst of all: he wasn’t always cheerful and good-humoured. It annoyed his parents, for they were perfect.

One day Sulo refused to smile and visitors and to perform the piece his mother Lempi had composed, I Am the Best. Instead, Sulo hid under the bed.

His parents dragged him into their fine car and drove to the Perfection Factory.

‘A faulty part for exchange.’ Sulo’s dad, Valio, lifted him onto the counter.

The assistant wrinkled his eyebrows:

‘This child’s warranty period is over. Take him to the Central Child Repair Shop.’

There was a queue at the Child Repair Shop. The reception clerk handed Sulo’s parents a catalogue, GREAT NEW FEATURES FOR YOUR CHILDREN and sat them down in a waiting room with a view straight into the repair shop.

There was a queue at the Child Repair Shop. The reception clerk handed Sulo’s parents a catalogue, GREAT NEW FEATURES FOR YOUR CHILDREN and sat them down in a waiting room with a view straight into the repair shop.

The repairers unscrewed the children’s imperfect parts and replaced them with football feet, virtuoso fingers and angel-faces. Sulo’s parents followed this happily, wondering whether they should get Sulo wings or an engine, or perhaps both.

Sulo was appalled; he did not want to be a super-child. He wanted to go away, but instead he turned into a stick.

‘Wake up!’ Someone or something nudged him. It was hard to say who or what was speaking, because it changed all the time.

‘I’m Maryam, I’m running away from an operation to remove my chameleonism. Let’s get out of here. Pretend to be as perfect as you can and follow me.’

Sulo took a deep breath and marched after the chameleon girl out of the Child Repair Centre, as brashly as a peacock superman. But just round the corner Sulo was his own imperfect self again: he tripped on Maryam’s heels at the bus stop. The girl smiled broadly and Sulo felt nervous, as he’d never travelled by bus before.

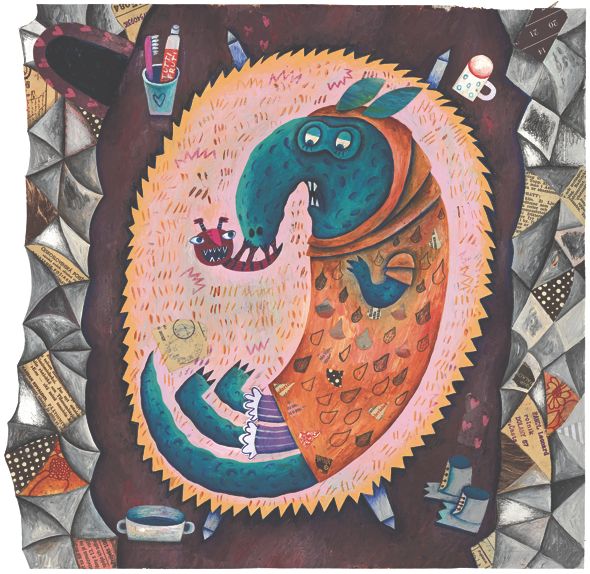

Iii and Rororo

The dinodonosaur Rororo was sleeping like a log in his warm cave. At least, until someone began to lick his snout.

‘Hey! I’m not food! I am the great fiery dinodonosaur!’ Rororo tried to shake the creature off, but it just giggled and bit him with its small, sharp teeth:

‘You sausage! Me Iii!’

Rororo was so badly startled that the strange creature dropped off his snout. Was this the frightening dinosaur told of in the dinodonosaurs’ old tales?

‘Are you a piranhosaur?’ Rororo was shaking with fright.

‘Me Iii,’ Iii declared stubbornly. ‘Me hungry. Me cold.’

Rororo sighed with relief. Of course Iii was hungry, otherwise it wouldn’t have even tried to eat the great fiery dinodonosaur! And it must be cold, it was completely naked and furless! Rororo gave Iii some grass and a winter overall and asked:

Rororo sighed with relief. Of course Iii was hungry, otherwise it wouldn’t have even tried to eat the great fiery dinodonosaur! And it must be cold, it was completely naked and furless! Rororo gave Iii some grass and a winter overall and asked:

‘Where do you live?’

‘Here. Me sleep,’ Iii announced, making a nest in Rororo’s bed.

‘That’s my bed! My home!’ Rororo was angry. ‘Get out, you ungrateful marauder!’

Iii took off the overalls Rororo had lent it and plodded quietly out of the cave.

Nevertheless, Rororo had a slightly bad conscience. So bad that he didn’t even feel like playing.

Rororo went out for a walk. Iii was sitting outside the cave. When Rororo returned home, Iii was still sitting there. When Rororo went for a wee in the bushes at night, Iii was still sitting in the same place.

‘Why don’t you go home?’ Rororo wondered.

Iii’s mouth widened into a broad grin.

‘Home, home!’ it hollered, bouncing into the cave.

‘OK. You can live here with me,’ Rororo relented. ‘But you don’t eat me, is that clear?’

Iii nodded vigorously and soon fell asleep in Rororo’s bed. Rororo snorted and curled up around his new friend. Next day, Iii and Rororo gathered more hay, which they used to make the bed bigger, but at night they slept curled up together again.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: children's books, illustration

No comments for this entry yet