No sex in Finland

31 July 2013 | Reviews

Tony Lurcock

Tony Lurcock

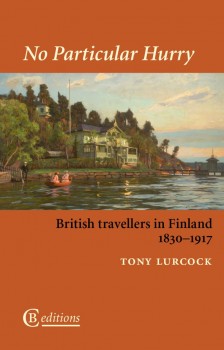

No Particular Hurry. British Travellers in Finland 1830–1917

London: CB editions, 2013. 278 p.

ISBN 978-0-9567359-9-7

£10, paperback

For British travellers of the late 18th- and early 19th-century Finland was mainly a transit area between Stockholm and St Petersburg, or on the way to exotic Lapland. A century later, the country was already a tourist destination in itself, a newly emergent nation state, though still subordinate to Russia.

Tony Lurcock’s anthology of travel literature about Finland is a sequel to his collection ‘Not so Barren or Uncultivated’: British Travellers in Finland 1760–1830 (reviewed in Books from Finland in June 2013).

The practical conditions of tourism were changing. English-language tour guides were being published, and Britain now had direct steamship connections to Finland, where rail, road and inland waterway traffic had been established. In 1887 the Finnish Tourist Association was founded with the aim of making life easier for foreign tourists on selected travel routes. However, the British – like many other foreigners – marvelled at some of the country’s curious features: the excruciating rural journeys by horse and cart, the wretched inns and strange choice of food, the rye bread and milk-drinking, and of course the sauna. But to this there were also exceptions, in the form of new, surprisingly resplendent hotels, world-class dinners and the life of the modern city.

Tony Lurcock has put together twenty-six excerpts about Finland by various authors, with a careful and comprehensive commentary on them and their British backgrounds. Finland was in a sense part of the British Empire’s conquest of the world during the nineteenth century – in other books many of the authors had also described other parts of the world.

The historical period in question is linked with two new themes that are dealt with in the book. The British Navy’s involvement in the Crimean War (‘The Russian War’) and its destroyer operations off the Finnish coast and the Åland Islands produced some interesting descriptions of Finland and its valiant people by British naval officers and civilian observers. They found the seamanship and shipbuilding skills of the Finns – formally their enemies – to be of an amazingly high standard.

The second topic is the strong international sympathy for Finland that manifested itself during the period of uncompromising Russification which began in 1898 and continued, with brief intermissions, until the First World War. Throughout Western Europe a campaign for Finland’s rights was mobilised and supported by a wide range of public figures, scientists and authors. In London the richly informative Finland Bulletin appeared regularly from 1900 to 1905, and in 1911 the Anglo-Finnish Society – still active today – was founded to promote the cause.

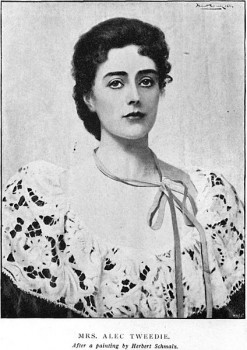

A third new factor was represented by female travel authors, the first of these being Elizabeth Rigby (Lady Eastlake), who in 1839 visited Helsinki on an excursion from Tallinn. Like many others, she admired Helsinki’s new ascendancy as a handsome nineteenth-century capital city. Typical ‘Victorian lady’ tourists of a later date included Anne Margaret Clive Bayley, 1895, Ethel Brilliana (Mrs Alec) Tweedie, 1896, the Finnish-born Sylvia MacDougall, 1908 (who wrote under the pseudonym Paul Waineman – derived from the name of the Kalevala hero Väinämöinen) and Rosalind Travers, 1908.

Of these authors, the best known to posterity is Mrs Alec Tweedie, whose book Through Finland in Carts appeared in 1897. Mrs Tweedie represented a new type of tourist: not merely an adventurer-explorer or author of light narratives in pursuit of curiosities, she was also an observer of social conditions who wrote in an incisive and amusing style. Comparing Finland with Britain, she saw a society that was in many ways more advanced, one in which women and even girls had full civil rights, and where public education, literacy, and social institutions were highly developed, with an absence of social conflict.

Ethel Brilliana Tweedie aka Mrs Alec Tweedie. Picture: after a painting by Herbert Schmaltz, Wikipedia

‘We were impressed by the fact of the marvellous energy and splendid independence of the women of Suomi. Of course, there may be cases of hysteria and some of the weaker feminine ailments, which are a disgrace to the sex, but we never came across any.

‘All this is particularly interesting with the struggle going on now around us, for to our mind it is remarkable that so remote a country, one so little known and so unappreciated, should thus suddenly burst forth and hold the most advanced ideas for both men and women.

‘That endless sex question is never discussed. There is no sex in Finland, men and women are practically equals, and on this basis the society is formed. Sex equality has always been a characteristic of the race, as we find from the ancient Kalevala poem.

‘In spite of advanced education, in spite of the emancipation of women (which is erroneously supposed to work otherwise), Finland is noted for its morality, and, indeed, stands among the nations of Europa as one of the most virtuous.’

(From Through Finland in Carts [1897] by Alec Tweedie)

It is worth noting that progressive-minded authors of travel books in those years viewed the countries of northern Europe as more or less ideal modern societies, where art and literature flourished under the leadership of Ibsen and Strindberg, and women rode bicycles.

The book’s author, Tony Lurcock, studied English at University College, Oxford. He became lecturer in English at Helsinki University and subsequently at the Åbo Akademi University. Returning to Oxford, he completed a D.Phil. thesis, and taught there as well as in America, until his recent retirement. Among the published travel reports Lurcock highlights some surprising Anglo-Finnish connections and discoveries.

One of these is the description of Lapland by Arthur J. Evans, archaeologist, keeper of the Oxford Ashmolean Museum and the discoverer of the ancient palace of Knossos on Crete. As a young man, in 1873 he travelled to Lapland with his school friend Francis Maitland Balfour. Balfour was the brother of Britain’s future Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour, and later died in an attempt to scale Mont Blanc.

In conjunction with the earlier volume, which starts in the eighteenth century, No Particular Hurry provides an excellent overview of British literature about Finland over a period of 150 years, as well as an account of the ways in which Finland has sought its place in the political and mental map of Europe.

Translated by David McDuff

A view at Ruissalo, 1903. Painting by Victor Westerholm (1860–1919), Kuopio Art Museum

Tags: Finnish history, travel, writing

1 comment:

12 February 2018 on 8:42 pm

Fun and informative at the same time

Thank you for the review