Damned nihilists

30 December 2008 | Extracts, Non-fiction

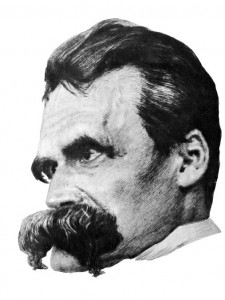

Much misunderstood: father of the superman, Friedrich Nietzsche.

The term nihilism is often bandied about, but often badly misunderstood. In extracts from his new book, Ei voisi vähempää kiinnostaa. Kirjoituksia nihilismistä (‘Couldn’t care less. Writings on nihilism’, Atena, 2008), the social scientist and philosopher Kalle Haatanen discusses the true legacy of Friedrich Nietzsche, nihilism’s high priest

The word nihilist is derived from the Latin: ‘nihil’ means, simply, ‘nothing’. When someone is labelled as nihilist or seen as representing nihilism, this has always been a curse, a mockery or an accusation, whether in philosophy, politics or everyday conversation. More recently, the word has generally been used to refer to people who do not believe in anything – people whose world-view is without principle, without ideals, barren. Often the closest word that flashes across the mind is ‘people-hater’. Sometimes, however, its meaning is comically unclear. In writing this, I have noticed that the word ‘nihilism’ has been used in the press to describe, for example, one of the autumn’s fashion megatrends (perhaps it means that dressing in black is ascetic, slightly futurist and machine-romantic, which is indeed well-suited to good people-haters). In the commentary on the Finland-Germany football match, it was noted that the German defence was ‘nihilist’, but I haven’t the faintest clue why, in what sense and with what reference this particular word was chosen. In addition to referring to a unprincipled but enthusiastic people-hater, the everyday word ‘nihilist’ can often take on a meaning implying passivity. In this case the subject is a lazy opportunist who cannot be bothered to believe in anything and whose world-view is characterised solely by endless irony and the feeling that everything has already been seen. Sometimes a synonym for such a dogma is ‘teenager’, but – as sociologists have taught us – many adults live a kind of prolonged youth today. I often feel sympathetic towards lazy people for whom the world does not exhibit that single error that must be put right….

![]()

Active nihilism is a slightly more problematic concept. It is used in reference primarily to Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the superman who is able to carry this insignificant, nihilist era heroically on his shoulders. The active nihilist is an exceptional individual who, in his endless appetite for life, encounters nihilist insignificance again and again, but nevertheless, in his passion for life, accepts even this nothingness – the most terrible of all thoughts – eternally shouting ‘Yes!’ in its face. Not an easy task, as we shall see….

Nietzsche shouts Yes! to life – and thus, inseparably, to death. Nietzsche’s essentially ancient Greek, pagan and Dionysian world-view deprecates life, which attempts only to protect life for its own sake. Such life is merely concealment within a self-satisfied and resentful shell. On the other hand, the question, ‘Who would Nietzsche like to see dead?’– a question to which so many people would evidently like to know the answer – is simply extraordinarily stupid. Those who pose it do not understand and have no idea that it is the nihilistic powers that deny and destroy life which Nietzsche has in his sights, and indeed not any individuals, races, or ‘lesser beings’. The superman is the human figure (or perhaps a wish/desire) in the Nietzschean conceptuary who no longer feels any resentment. The superman is free of conventional moral codes because he sees them, first, as artificial, and second, as ways of controlling crowds or masses. I do not wish to make Nietzsche excessively tame: he certainly also says that morals are produced by herd-souls, and are suitable for them. In his tumultuous texts he curses those people to the lowest circles of hell and lifts others to the heavens. Nietzsche does not feel pity – because he loves life.

But then there are the lunatics. The proponents of the school murders at Columbine, USA, declared themselves nihilists. Last year, in the testament he left on the internet, the Finnish school murderer Pekka-Eric Auvinen demanded that he should not be psychologically analysed, but that he and his actions would be met face to face. In both cases, the Nietzschean undertone was clear, in part even correctly understood (the avoidance of psychological analysis, the inevitability of violence). – But the idea that rising to the far side of good and evil would mean merely resisting the predominant morality of pity and, in its name, would allow for pitilessly slaughtering lesser people! No.

Listen up: such resistance in fact only preserves the morality in question in its negative form; it is a resentful reaction in a world of resentful morals. Nietzsche was much more radical. How banal, unaristocratic and unaesthetic a school killing is! It is true that Nietzsche’s radical philosophy, with its emphasis on the advent of the totally unexpected and, on the other hand, the destruction of the old, has no logical endpoint that might somehow reign in destruction or even give it a purpose of any kind. This is what is meant by radical thought. Still less does it offer advice or guides for the realisation of some sort of programme, particularly if this breaks with the values of aesthetic aristocracy. There may no longer be any use for the moral and the ethical, but if something True, Beautiful and Great in this insignificant world still, or again, receives an echo, it is aesthetics. If Nietzsche were to confront the actions that have been carried out in his name, he would turn away in horror. Not out of pity perhaps – the world is a cruel place – but out of revulsion: his ‘followers’ put in to practice a ‘programme’ in which radical, untamed violence is shackled to a perfect, life-despising lack of style….

In nihilist philosophy – in other words, of the kind found in real literature, not in internet nonsense or fanatical interpretations – no one gives instructions or reasons for killing, and no encouragements to such actions are contained in any texts. The last thing a Nietzschean superman would do would be to ‘overcome himself’ in such an action, however much he were to move on the far side of good and evil….

![]()

Some people adopt a particular version of nihilism as their ideology or principle, leaving their testament, public statement or video on the internet, and are guilty of indescribable violence. Then the term ‘nihilism’ takes on a different content from simple hatred of humanity. The worst self-justifications used by killers are often found in the Nietzschean concept of the superman. True: the superman is an exceptional individual; true: the superman is on ‘the far side of good and evil’; true: the superman despises the herd-soul, democracy and the equalising of everything; true: the superman cannot be psychologically analysed; true: the superman is destructive.

Let me briefly examine these arguments. The analytical method is, however, not the best approach, for Nietzsche’s philosophy is not easily susceptible to logical or exhaustive explanation. I am, anyway, of the opinion that it is not possible to present an overall picture or certain truth concerning Nietzsche’s tumultuous and often fragmentary oeuvre. Rather, the question is of more or less about successful interpretations. I shall now, however, attempt to unravel this argument a little.

First, the superman would never act reactively and respond with violence to some circumstance or state of being, or by attacking it resentfully. The destructiveness of the superman lies in the creation of the new, which does not serve any purpose or dogma. The ‘object’ of destruction is the old world of values, but only in the sense that the creation of the new always destroys the old. Second, the superman is ‘beyond good and evil’, but at what point did the interpretation change in the blink of an eye to being ‘on the side of evil’? Nietzsche’s vision may nourish irrational destruction (because it has no direction), but existence on the far side of good and evil means, first, a grasp of the accidental nature of the predominant moral values and, second, an aesthetic rising above them, not a recursive return to the programmatic destruction of the old. Third, despising the mass man does not mean despising people, it means despising the forces that trivialise life.

![]()

If nihilism is, quite rightly, interpreted as a kind of attempt at liberation from the burden of history, Christianity and humanism, it must be understood how arduous this liberation is. In the opinion of some, it is quite impossible – most closely comparable to Baron von Münchhausen when he rose from the marsh by pulling himself up by his own hair.

It is not, in other words, easy to become pagan again. For that reason, I am nervous about sociology’s sometimes too easily applied prefixes, post- and neo-. For example, the French sociologist Michel Maffesoli, who constantly draws on Nietzsche, often speaks over easily of ‘neo-tribalisation’ or ‘neo-paganism’. In his conception of history, the Apollonian period with its emphasis on reason and harmony is once more making way for the new coming of a Dionysian age marked by passion, drunkenness and danger. Maffesoli speaks of an ‘orgiastic age’. The idea is interesting (I, at least, periodically become enthusiastic about it), but a couple of years ago fifty per cent of sociology dissertations were on the urban tribes of club cultures and cities. Neo-pagans and post-modern orgiasts who have rejected rationality? Oh well. Then they grow up, there’s work in the morning, and they have to go home early – if they have ever left it, as there are the children to be looked after.

The attempt to become pagan again, or ‘to able to be superficial’, as Nietzsche put it, is perhaps best described in the Bertolt Brecht text that is often used in death notices: ‘And when she was finished they laid her in earth // Flowers growing, butterflies juggling over her… // She, so light, barely pressed the earth down // How much pain it took to make her as light as that!’ [‘Song about my mother’, translated by Christopher Middleton].

When used in death notices, it is fairly clear that this beautiful text of Brecht’s makes reference to a death caused by a long, painful illness, in which death really comes as liberation or oblivion. The same is true of nihilism, when taken seriously. Nihilism is that illness. It is a lifelong struggle against (easy) life. It has no logical conclusion – some kind of post-moral age – instead, the question is of a continual struggle against various moral doctrines, collections of rules, theologies as well as triviality. For the active nihilist, freedom is does not lie in someone saying how things should be done; neither is it to be found in throwing oneself into the belief that nothing means anything. The passive nihlist acts entirely according to the logic of opposition. He finds freedom in both extremes. ‘OK, I could do that’ and ‘What point is there to anything in the end.’ Perhaps a more accurate analogy – better, at least, than the illusion of a post-moral age – is the fate of Sisyphus (Camus’s favourite, by the way), who is condemned eternally to roll a boulder up a hill. When the boulder reaches the top, it naturally rolls down again, and Sisyphus has to begin all over again, forever. That is also the fate of the nihilist.

![]()

Philosophically nihilism – in the eyes of Nietzsche and Heidegger, the entire history of western thought, from Plato onward – never reaches a conclusion, can never be overcome. It can be attacked, attempts can be made at destruction, at radically new thought, just as Nietzsche and Heidegger did. The Nietzschean idea of coming, the appearance of something completely new, is thoroughly destructive. It is an anti-nihilist radical force which destroys the past and the existing, but it has no inner definition or future horizon. The thinking of something completely new, the coming of something completely new, is not born of given conditions and does not obey the predominant laws. In other words, it destroys the conditions of its own coming. It does not return and cannot be reduced to causes or circumstances. It is completely unpredictable. For this reason the extreme anti-nihilist pathos of Nietzsche’s philosophy has been called nihilist – it has no content, it is nothing.

The question, however, is of something completely different. Niezsche does not emphasise emptiness, but something destructive, radically creative of the new and destructive of the old. It cannot be shackled or anticipated – or considered to represent something good or evil. It is aesthetics in the most radical sense of the word. It is Nietzsche’s active, heroic and aesthetic nihilis: pure force, which does not bend to truths or purposes. For precisely that reason it is able to destroy the worst curse of our age, nihilism.

![]()

There is one more, in some ways more comforting, way of thinking about nihilism. It is the desire to remain silent. In addition to Nietzsche, the 20thcentury philosophers Martin Heidegger and Hannah Arendt also constantly emphasise activity, creation and pathos. Such things can be tiring. The same is true of the American analysts of conservative national values and bourgeois public life and their horror of couch potatoes and ironists. In this connection I feel a sneaking sympathy for passive nihilists and their lazy irony. ‘The time is out of joint,’ as Hamlet said, but could some handyman not be paid to fix it? I don’t feel like it. I don’t have the energy. Forgetting to vote, political inactivity and watching the shopping channel all night feel more and more tempting.

There is one branch of philosophical nihilism that I have not dealt with in any detail because it is not linked with the continental philosophical tradition of nihilism. It is the habit in western philosophy of describing the word through logical sentences and language. Ludwig Wittgenstein, in particular, is considered a representative of this kind of nihilism. He apparently hated unclear sentences and wished to see philosophy as a language game, and language as limited, and, in fact, the whole of philosophy as action. Philosophy makes philosophy and thus it is quite pointless to ask what philosophy is. It is an obscure question to which one can never receive an answer.

Stanley Rosen, author of perhaps the most significant study of nihilism in recent years (although it was actually published in 1969) calls this Wittgensteinian desire for clarity a ‘yearning for silence’. Rosen considered it little less than an obsession, which wanted to remove all lack of clarity from philosophy and achieve a kind of peace in which philosophy works and A = A.

In Derek Jarman’s stylised film Wittgenstein, this desire for clarity and thus silence tortures Wittgenstein throughout his entire life. Jarman, too, sees this nihilism as an unsupportable state in the end. In the final scene, a Wittgenstein seen once more as a small boy examines the world he has created. It is purely a film set: an empty background and a mathematical grid or co-ordinate system. There the poor young Wittgenstein would like to fly in the plane he has built, but the world he has created is cold, barren of imagination, and empty. It leaves no room for flying or the imagination. The ‘yearning for silence’ was finally victorious.

I am an optimist: perhaps a suspicion of pathos combined with lazy irony is a suitable mixture of nihilist elements. At least it seems like a world one might be able to live in.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

(First published in Books from Finland 4/2008.)

Tags: Nietzsche, nihilism, philosophy

1 comment:

27 July 2009 on 11:16 am

Very educational and interesting article. I can only thank you for that.