Form follows fun

4 December 2012 | Non-fiction, Reviews

The house that the artist built: ‘Life on a leaf’ (2005–2009, Turku). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Jan-Erik Andersson: Elämää lehdellä [Life on a leaf]

Helsinki: Maahenki, 2012. 248 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-5872-82-4

€42, hardback

‘I am Leaf House –

root house, sky house.

Enter me, be safe

And wander, dream.

The artist’s I is all our eyes….’

In the garden: red ‘apple’ benches designed by the English artist Trudy Entwistle. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

We all live – exceptions are really rare – in cubes. Not in cylinders or spheres, let alone in buildings of organic shapes like flowers or leaves; and houses in the shape of a shoe, for example, belong to the fairy-tale world, or perhaps to surrealism.

Artist Jan-Erik Andersson wanted to build a fairy-tale house in the shape of a leaf, and that is what he did (2005–2009), together with his architect partner Erkki Pitkäranta. Instead of the geometry of modernist architecture, he is inspired by the organic forms of nature.

Andersson’s house project, entitled ‘Life on a leaf’, also became an academic project, resulting in a dissertation at Finnish Academy of Fine Arts and now a book, including a detailed journal of the building process itself. The artist was at first advised, by a professor of architecture, not to proceed with his building project – he wouldn’t ‘like living in the house’, he was told.

The first floor ‘sound bridge’ goes along the ‘stem’ of the leaf house. Photo: Matti A.Kallio

Other architects, examining the project, had problems with the term ‘an architectural work of art’ – a work of art, yes, but the long-prevailing laws of modernist architecture are about geometry, masses, modules, mathematics, light and the capacity of repeat manufacture, realisation irrespective of place.

It is true that housing great numbers of people in buildings in the shape of flowers, for example, is a mission impossible – but, undaunted, the artist went on to challenge the idea of the white cube.

Inside the leaf: living room (ground floor). Photo: Matti A. Kallio

Andersson has also been inspired by art nouveau (c. 1890–1910), or jugend, as it is called in Finland. Its architects applied organic forms to the classical model of space, the cube; ‘Life on a leaf’ discards the cube, instead exploring organic space, testing its functionality as a living space.

As early as in 1908 the architect Adolf Loos proclaimed that ‘ornament is crime’. Andersson is eager to commit the crime of ornamenting his house in various ways; he is inspired not only by the highly ornamental art nouveau – Gaudí, Hundertwasser amd Finnish jugend architects, as well as Dalí and the Russian architect Konstantin Melnikov, for example – but also by his own stories, memories of childhood, fairy-tales and travels.

‘Life on a leaf’ is the opposite of the masculine, abstract austerity of the white cube celebrated by the great Le Corbusier and his followers. A white cube distances itself from nature, whereas ‘Life on a leaf’ attaches itself to it: inside the house, columns, pillars and the shape of the windows create a feeling of being in a forest where the views are restricted and formed by tree trunks. According to Andersson, ‘man, whose genetic structure is designed to function in nature, thrives in surroundings based on the forms of nature.’

Family house: living room and the artist himself in the kitchen (ground floor). Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

The house and its surroundings contain works by twenty artists whom Andersson invited to contribute to the project. One of them is the poem, ‘Leaf House’, cited above, by the British poet Robert Powell; it is painted on the inside of the front door, but backwards, so it can be read only via the mirror on the opposite wall.

Another artwork is a video depicting New York’s Grand Central Station that can be watched through a crack in the first-storey floor. A ‘sound bridge’ by the American artist Shawn Decker is also installed in first floor, with recorded sounds of the nature outside the house – wind, bird, trees, rain.

Bathroom: design on the wall by the artist’s 6-year-old son Adrian. Photo: Vesa Aaltonen

Obtaining a building permit was not easy: in Finland regulations are strict. Andersson was finally allowed a site on an island near the centre of the city of his native Turku – the Leaf has no neighbours in sight… The uniformity of planning favours cubes.

Reading this lively, surprising and very well illustrated account of journey from a dream to a house, one is reminded of the artist and writer Tove Jansson’s family house, in the form of a cylinder, which she designed for her Moomin characters: an icon of safety, warmth and cosiness – fairy-tale dream house as well.

Inside the bluebell: views of the city of Turku. Photo: Matti A. Kallio

The artist’s family has lived on, or rather, in their ‘leaf’ for a couple of years now. And yes, they do like it.

On the top of the building there is a bell-shaped, blue glass dome. Looking at the starry skies, sitting in the bluebell, it must feel like living in a fairy-tale – with all mod cons. The building, of 143 square metres, lacks a sauna (almost a must in Finnish houses) and a garage, to save money and energy, recycled building materials were used, and the house is heated with geothermal heating.

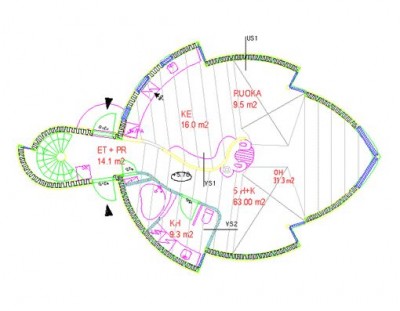

Organic form: ground plan of the Leaf house

What is art and what is architecture may be debatable – but the challenge Andersson took up in building something that wasn’t ‘architecture’ was a successful one, at least measured by the livability.

The architect Louis Sullivan (1856–1924) coined the phrase ‘Form [ever] follows function’; it may never have occurred to him, his contemporaries or his followers that what follows from form can also be fun.

English edition is to be published in early 2013:

Jan-Erik Andersson

Life on a Leaf

Maahenki, ISBN 978-952-5870-83-1

Tags: architecture, art, Finnish nature, Finnish society, photography

No comments for this entry yet

Trackbacks/Pingbacks:

19 March 2013 on 2:44 am

[…] http://www.booksfromfinland.fi/2012/12/form-follows-fun/#more-21632 […]