Figuring out father

18 October 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

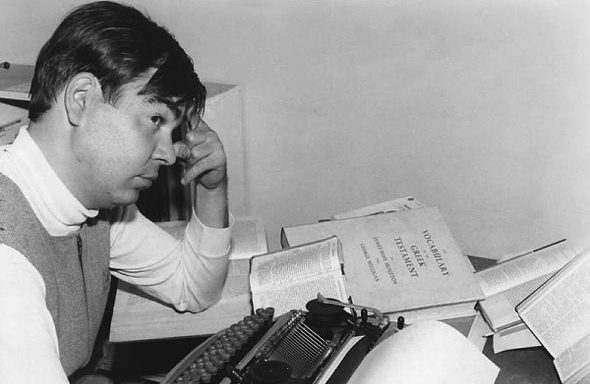

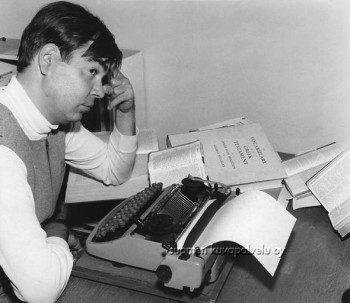

Pentti Saarikoski (1960s). Photo: Otava/Nikolai Naumoff

The poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski (1937–1983) jotted in one of his journals: ‘I have never cared for relatives.’ Thirty years after his death one of his five children set out to find out what his father was like – by reading almost all he left behind in writing; these comments by Saska Saarikoski are from his Sanojen alamainen (‘Servant of words’, Otava, 2012), an annotated selection of Pentti Saarikoski’s thoughts

Pentti Saarikoski died when I was 19. I remember complaining to my mother that I had not yet even got to know my dad. My mother answered: You’ve got plenty of time, the real Pentti is to be found in his books. She did not know how right she was, for she meant Pentti’s published books, not knowing what a mountain of texts awaited its readers in the archives of the Finnish Literature Society. Pentti had written everything down in his diaries.

I read Nuoruuden päiväkirjat (‘Youthful diaries’), published soon after Pentti’s death in 1983, as soon as they were published, but when his Prague, Drunkard’s and Convalescent’s Diaries appeared around the millennium, they went straight on to my library shelf. I was not terribly interested in the ramblings of Pentti’s alcoholic years.

It could be that my reluctance was influenced by the cool attitude I had adopted from early on in relation to my father. Other people were welcome to consider him a genius; for me, he was a father who did not telephone, write or come to see my football matches. I didn’t call him, either; for me, it was a father’s job.

Although my attitude to Pentti has since softened, I still cannot read the endless navel-gazing of his books – however rawly truthful or finely written it may be – without thinking that my father’s life could have been much easier if he had been even just a little more interested in people other than himself.

According to Pentti’s diary entries, art should not be untarnished, declamatory, thought-provoking, conspicuous, let alone objective. But it would be no bad thing if art, or even poetry, were weed-wild and iconoclastic. Over the years, his thinking about writing became increasingly zen-like. In his final years he often compared writing to walking, talking and breathing.

If Pentti had had a theory of art, it could have gone something like this: art is a way of examining the world.

In his Nuoruuden päiväkirjat (‘Youthful diaries’), Pentti asked: ‘Will the riddle of the world finally be solved by science or poetry?’ Stupid question, he answered; poetry had already solved it in the Old Testament.

In his diaries, Pentti remarks many times that he does not read much poetry. As for reading novels, the difficulty lay in the fact that they made Pentti think about how much better a book he would have written if only he could be bothered.

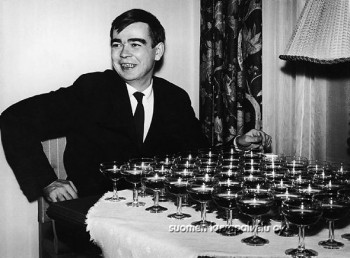

Pentti Saarikoski at a publisher’s party, December, 1965. Photo: Nikolai Naumoff / Otava

Why did Pentti drink? Anyone who has ever opened a bottle of wine can probably take a guess. To forget his shyness, to put up with people, to extinguish his superego, to give him the courage to approach women, to relax, to allieve anxiety, to ease depression. But whatever the original reason, in the end Pentti, like all alcoholics, drank in order to carry on.

For many years, he corked the bottle whenever he began to work. The last book he wrote when completely sober was, he said, his poetry collection Kuljen missä kuljen (‘I go where I go’,1967).

‘People who know nothing about alcohol imagine that the aim of drinking is to get drunk, when in fact it is delirium, which should really be written Delirium, as it is a place, not a state of being.’ (Juomarin päiväkirjat, ‘A drunkard’s diaries’, 1967).

In his relations with women, Pentti was a child of his time. Boys were privileged in his family, and Pentti, because of his gifts, particularly so. No wonder that Pentti’s early writings express stuffy gender roles and stereotypes, sometimes even disparagement of women. Pentti had internalised the madonna-whore idea while young, and never completely rid himself of it, however hard he tried. He needed a mother-figure, but desired a whore-woman. The combination of these two roles in the same person was a constant problem for Pentti. In his later years, Pentti was a supporter of equal rights for women, if not emotionally then at least intellectually.

Pentti was, both spiritually and physically, as far as it was possible to be from the ideal man of the 1950s: not bold and strapping but delicate and bird-boned. I cannot help wondering how different Pentti’s life would have been had he not been born just before of the war, in 1937, but for example in 1963, like me.

In that case he would not have had to grow to manhood in the shadow of alpha males such as Mannerheim, Kekkonen, Antti Rokka [of the war novel Tuntematon sotilas, The Unknown Soldier, by Väinö Linna] or John Wayne, but could instead have identified with androgynous men such as Mick Jagger, John Lennon, David Bowie and Boy George. He would have been able to paint his eyes with kohl and hang out in decadent clubs with other beautiful youths.

In his own time, a narcissist like Pentti, a metrosexual interested in men as well as women, was a strange bird, but in the more urbane, more permissive and more international Finland of the turn of the millennium it would have been much easier for him to live and breathe. Perhaps in that case his spirit might have lasted longer. But we are thrown into our time, and even the most gifted of us cannot entirely escape it.

Concerning Pentti’s literary career, the dominant intepretation is that of the critic and biographer Pekka Tarkka, according to which the brilliant young poet lost himself, in the 1960s, in politics and booze, but returned from his wanderings and crowned his career with the classic works of the 1970s and 1980s. I do not disagree.

Pentti followed, in astonishing detail, Finnish power games, Marxist discourses and the ins and outs of international politics. This, of course, reflected the spirit of the time. After a couple of apolitical decades, it is hard for us even to imagine the progressive imperative of the 1960s and 1970s, in which everyone with a public role was expected to act consciously, participate and take a stand.

A text was once to be found in the inner courtyard of the Greek temple of Delphi: Gnothi seauton, Know thyself. The philosophers interpreted this to mean that, because man was part of the cosmos, he who really knew himself knew the entire world.

Pentti Saarikoski (1960s). Photo: Nikolai Naumoff / Otava

Pentti took up the challenge posed by the Greeks: he attempted to learn to understand himself, and the world. In the end, both tasks turned out to be impossible. Pentti concluded that understanding is always a stop-frame image, in other words violence and death, whereas life is movement, dance, the flow of everything. This, then, was the way in which Pentti answered the question that he had set out on his journey to explore: one cannot understand oneself, and therefore not the world either. There is therefore no point from which one could control the world; platos, pauls, marxes, lenins and stalins are wrong, every one of them.

Pentti’s literary oeuvre is an image of these two human experiments, the personal and the societal. If I had to give a single name to his collected works, it would be difficult to invent anything better than Epäonnistumisen kronikka – ‘A chronicle of failure’. This does not refer to literary quality.

I found, in the pages of books, my father, who described his feelings and thoughts in a way that I have heard only a few even of the living do. Or how many people have heard their own father talking about their dreams, their problems of self-esteem, their mental health, their sexual complexes, their alcoholism, their lies, their fear of death? I have, now. I am glad that such an acquaintance was still possible, almost 30 years after my father’s death. My joy is, though, slightly shadowed by the fact that in death my father, as in life, belongs to me no more than to any one of his readers. I have a father, but he is not mine.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: biography, literary history, poetry, writing

No comments for this entry yet