So many words

25 April 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

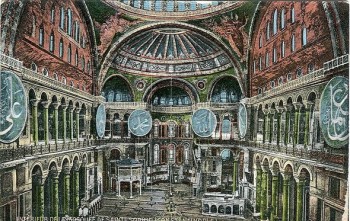

Hagia Sofia, Istanbul: from basilica to cathedral to mosque to museum. Postcard, c. 1914. Photo: Wikipedia/Xenophon

Sacred spaces, repositories of free speech, places of healing? Teemu Manninen awaits the day when libraries become virtual, enabling anybody to visit them, without having to travel across land and sea

The Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Vatican Library, the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, New York Public Library, the British Museum Reading Room, the Real Gabinete Portugues De Leitura in Rio De Janeiro, the Library of Congress and the National Library of Finland.

What do all of these have in common, except the obvious fact that they are all famous libraries? To put it another way: why are these famous libraries so famous?

It is not because they have books in them, although that has become one of the main tasks of the library system in the modern world. But a library is not simply an archive. If we in the West are a culture of the book – a culture of the freedom of information and expression – then a library is the architectural incarnation of our way of life: a church built for reading.

Famous libraries are like famous cathedrals, and one could say of them that ‘what is more important in a library than anything else – than everything else,’ as the American poet, dramatist and librarian Archibald MacLeish wrote, ‘is the fact that it exists’.

A library is the medicine chest of the soul, open for all, and used by all, rich and poor, wise and stupid; it is ‘a place of safety for the bibliophile’, as the writer and editor Orlando Whitfield recently said in the Paris Review, trying to explain the fascination the London Library (established in 1841 by Thomas Carlyle) has held over his soul from the time when he was a boy and would spend every Saturday there with his father, the two of them flinging themselves ‘like hunters into the warren of the stacks’.

The London Library became ‘an addiction, an obsession’ for him, as libraries tend to do for those of us who care deeply about words and ideas. I myself have spent numerous hours, sometimes whole days in libraries small and large, wandering aimlessly in basements and upper stories, moving my eyes a book title at a time from left to right, down and up the shelves, head craned in an awkward position, slouching forward in that slow gait of the prospector of rarities and serendipities, waiting for the miraculous event when something simply clicks and, by instinct or by foreknowledge we do not know, an arm reaches out and a book is retrieved, a fruit of knowledge sampled there and then in its pristine glory.

It is because of the immense enjoyment I receive from these ventures into the bibliographical unknown that I have become a staunch supporter of digitisation. I believe that we must digitise every book in the world and make them available for everyone in the form of electronic lending libraries.

We must do so quickly, because I fear that we may, as a culture, be losing our grasp not just on the task of libraries – to administer and uphold the rites of universal knowledge and the freedom of information – but also on what makes the best of our libraries, the famous ones, so well-suited to this task: the simple fact that they are well-designed and beautiful.

If the library is akin to a secular church, then we must understand that the architecture of a library is not incidental to its cultural task. And indeed, there is a singular feeling one gets when walking through the stacks of a very old or very beautiful library, described by Charles Lamb, the nineteenth-century essayist and critic, who said that ‘all the souls of all the writers’ seem to repose there ‘as in some dormitory, or middle state. I do not want to handle, to profane the leaves, their winding-sheets. I could as soon dislodge a shade.’

But there is equally a feeling one gets when one delves ever deeper into the electronic archive, leafing through databases like Early English Books Online, WorldCat, Project Gutenberg, the Internet Archive or Google Books, piecing together information from disparate sources and combining them in the exact right search string. This string produces, for example, a digitised representation of the first edition of Charles Montagu Doughty’s early science fiction epic in verse, The Cliffs (1909) – just that kind of book I could not even have dreamed might have existed, but upon finding become enrapturously engrossed in.

The sorry fact is that this ecstatic experience is often come by only after tedious hours of navigating through incoherent menus, unusable interfaces and paywalls, incomplete scanning jobs, incompatible text encodings, or – what is most annoying – unnecessary copyright protections extending well beyond any reasonable amount of time. Personally I believe all books should be released into the public domain after a writer’s death, and a scan of a 16th-century playbook should be available through my ereading device just like the latest bestseller is; and the experience should be as easy, enjoyable and beautiful as a visit to a well-designed library.

So far, this has seemed like a pipe dream, mostly due to the need to monetise new technology. As much as there is talk about the coming of the ebook, I find it abhorrent that it is most often only thought of as a commercial product, and not a way to make libraries a part of the information ecosystem of today’s interconnected world.

Just think: for almost two decades now the sum of human literary production could already have been immediately available for almost anyone with an internet connection, but due to either the bureaucratic ineptitude of this archive’s administrators or the infinitely abysmal avarice of the money-grubbing mercenaries who own the ‘rights’ to the writings of long dead authors we are denied something that is our inalienable cultural birthright.

As long as these scoundrels get their way, the digital version of a cathedral such as the Bibliotheque Nationale or the British Library awaits its coming. I hope that day is not long off.

Tags: ebooks, libraries, literary history, publishing

No comments for this entry yet