The coder’s Latin

30 October 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

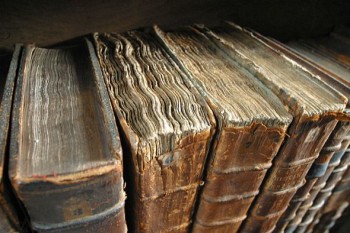

Pleasant interface still? Old book bindings (Merton College library, Oxford, UK). Photo: Wikipedia

Writing is arguably brain-control technology, notes our columnist Teemu Manninen. Writing might not be on its way out, at least not quite yet, he thinks, but the printed book might not stay with us for ever. And would that be a happier world?

When the future of literature is discussed, either here in Finland and elsewhere, topics usually revolve around changes in the economics and practicalities of reading, writing, and publishing: how will writers and publishers get paid, and how can readers find more books to read.

What is taken for granted in these instances is that literature itself will continue to be something that exists in a recognisable way – which itself of course implies that writing itself will remain a viable mass medium for the transmission of information over the transcendent, enormous, unfathomable gulfs of space and time, as it has been for thousands of years.

Will it, though? Who’s to say that in those far future times, when even simple human tasks would appear to us then-ancestors (were we to inhabit the bodies of those grand+n-children of ours) as the stuff of pure fantasy, that writing will not have been replaced by something more efficient: telepathy, say, or perhaps highly-developed data visualisation techniques far beyond our present understanding of how human minds work.

Even if such fantasies never come true, the way in which writing functions in the world is already changing – if you only stop to think about it for a while.

If human culture has been a culture of the book, a culture of writing, for the last few millenia, it might be because writing has exerted such a strong influence on the way in which we understand the world and ourselves – this not only because of what we say when we write, but because of what writing also is: brain-control technology.

Writing is, after all, a curious invention. It is not natural to the human brain: we need to develop skills for coding and deciphering, when we learn to read and write – and by learning those skills, we change our brains.

For instance, Vilém Flusser, the influential Czech-Brasilian media philosopher, was wont to say that writing is the chief begetter of historical consciousness: that because we have learned to write, we have gained an idea of history as an ordered, sequential progression of events.

Myth moves in cycles, Flusser said, like speech – it doubles back on itself, repeats, stammers, walks in circles. Writing gifts us with the ability to order our thoughts, to arrange them in a logical sequence, and also allows us to review our thinking objectively. When we write, we take pauses, lift ourselves from the page, go back and read what we have said and then revise it.

This is the model for critical thought. It is not an abstract process hidden inside our minds, some kind of thought-yoga people learn in the university: it is an inevitable form of behaviour that occurs when we write.

Another central emblem of our culture of writing is the book as a material object, and the way in which it functions as an interface, a point of access to the ideas it holds. Humans are tool-making animals. We think with our hands. Concepts relating to understanding, scientists have noticed, are deep down almost always metaphors of touching, holding, and grasping.

The book is a tool you hold in your hand. It gives information about itself by touch: you move materially through its pages, opening it at different places. Recently, studies of digital reading have shown that touch-screen reading changes how we remember things: people who read from digital devices do not retain details of plots as well as people who read printed books.

This might be because the physicality of the book itself conveys information: it allows us to feel the location of a book’s beginning, middle, and end with our fingers. Could these three unities of Western dramatic art be, in fact, products of the Book? Imagine it: the Bible, our Book par excellence, not only divides time and existence to beginnings, middles and ends, but also eras (chapters, books, parts), and what’s more, gives history as a whole a structure that is either comic (for those who are saved in the end) or tragic (for the other guys).

What is the internet compared to the Book? Where is its beginning, middle or end? The archive of Big Data is vast and meaningless, undecipherable. But, we forget, so was the Book. For ages, reading and writing were skills only the rich could afford to train, and when the Bible provided the model for learning, the shape of history and the fate of men, for a long time only priests learned in Latin were allowed to decipher the word of God.

In some ways, we are living through a new Dark Age. Most of us are illiterate in computer code, the contemporary Latin our modern clergy uses to write the programs that run our lives. The churches of Apple, Amazon and Google make it possible for their congregations to use it for their own good, but access is granted only if you buy in to their interpretation of how the world of information ought to be revealed.

Categorised, monetised, functionalised, the stuff of our informatic lives, the laws of modern culture, are pushed onto our tablets, and we touch them, thinking that we give the commands, believing things are within our grasp – but the glass is always there between us and those who stand on the other side.

Vilém Flusser believed that writing was on its way out, that it would be replaced by images and code. I don’t entirely agree. I believe text, in some form, will be with us for a long time to come, but I’m not so sure about the printed book.

All I know is that when we no longer leaf through pages, when there are no more bookmarks and no more stacked paragraphs progressing from beginning to end, when we cannot be on the same page anymore, flush with the edges or not; when we are unable to read between the lines, or throw our books against the wall, or open them haphazardly to find serendipitous wisdom; when we can’t write on the margins or rip pages out of the book of life, then the world, along with us, will be different.

No comments for this entry yet