Reading matters? On new books for young readers

9 January 2014 | Articles, Children's books, Non-fiction

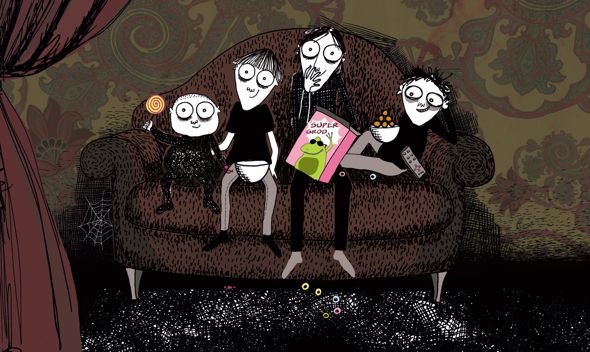

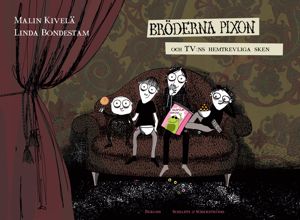

The Pixon brothers don’t read books, they love the telly: story by Malin Kivelä, illustrations by Linda Bondestam (Bröderna Pixon och TV:ns hemtrevliga sken, ‘The Pixon brothers and the homely shimmer of the telly’)

Finnish picture books for children have long been reliable export goods around the world. In the last few years, a number of novels for children have come along in their wake: works by authors such as Timo Parvela and Siri Kolu have been translated into a good many languages.

Now young adult literature has also blazed a trail on to the international market – in what also seems to be almost a matter of precision timing with regard to the Frankfurt Book Fair 2014. Finnish publishers have been investing in their home-grown lists of children’s and young adult books ever since the turn of the millennium, and now the time has come to harvest the fruits of their long-term efforts.

Salla Simukka’s Lumikki (‘Snow White’, Tammi) trilogy made history even before its final instalment was published in Finland. In the space of six months, translation rights for the series had been sold to 37 countries in fiercely contested auctions – a completely unprecedented scenario for a Finnish author. The crowning moment in a triumphant year arrived in December 2013, when the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture awarded Simukka the Finland Prize, which is granted each year in recognition of a significant artistic achievement or breakthrough.

The first volume in the Lumikki trilogy, Punainen kuin veri (‘As red as blood’), combines a traditional coming-of-age portrayal with a gripping thriller-style plot via the character of Lumikki Andersson, a traumatised school bullying victim. Salla Simukka has made innovative use of classic tales, currently popular in the international media landscape, in her narrative in a way that is capable of entertaining adult readers as well.

The first recipients of the Nordic Council’s brand-new prize for children’s and young people’s literature, worth €43,000, were Seita Vuorela and Jani Ikonen for their novel Karikko (‘The reef,’ WSOY, 2012). Like Salla Simukka’s trilogy, Vuorela and Ikonen’s novels show a conscious wish to appeal across artificially imposed boundaries between reader demographics. Both works specifically mention two target audiences on their back covers: young adults as well as adults.

Meanwhile, slight confusion arose among observers of the young adult book world when the nominations for the Finlandia Junior prize were announced: half of the nominated titles were not primarily children’s or young adult literature. Aapine (‘ABC’, Otava), a collection of poems with alphabet-based rhymes written by poet Heli Laaksonen in the south-western Finnish dialect, Marja Björk’s Poika (‘The boy’, Like), depicting the experiences of a transgender youth, and Vain pahaa unta (‘Just a bad dream’, Otava) by Aino & Ville Tietäväinen, about children’s nightmares, have all enjoyed more popularity among adults than children.

Even so, the attention paid to children’s and young adult books in the media has become more random and patchy. Traditional visits by authors – ‘travelling preachers’ – to promote books at various educational events and libraries, nurseries and schools have taken on greater importance in spreading the word about the wide variety on offer.

Finnish children’s and young adult writing has its finger on the pulse of the modern world even more firmly than before, providing keen-eyed reflections of today’s society. Fathers with busy careers feature in Isä vaihtaa vapaalle (‘Dad takes time off’, WSOY), a picture book by Jukka Laajarinne and Timo Mänttäri, as well as Meidän isä on hammaspeikko (‘Our Dad is the Tooth Troll’, Otava), the debut work by journalist Saska Saarikoski, who is the son of the well-known poet and translator Pentti Saarikoski. In each of these books, a father is willing to make compromises for the sake of the well-being of his family as a whole. Children’s books do indeed still promote ideals: by and large, not many fathers with young children make such sacrifices on behalf of their families in real life.

On the other hand, two works by Kreetta Onkeli – her children’s novel Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory,’ Otava) and Selityspakki (‘The answer kit’, Otava), a collection of little stories and explanations – ensure that kids also have access to no-nonsense information about the real world and contemporary society. Onkeli does not sugar-coat issues such as exhausted parents, social inequality and the effects of social exclusion.

Finnish educators monitored the results of the latest PISA survey carried out in OECD nations with concern. Finnish pupils’ previous world-beating performance was hanging in the balance. The largest Finnish publishers have dramatically reduced their output of children’s books for beginning readers: a very short-sighted strategy.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

Links to the reviews

Ville Hytönen & Matti Pikkujämsä:

Ville Hytönen & Matti Pikkujämsä:

Hipinäaasi, apinahiisi

[Donkeymonkey]

Riitta Jalonen & Kristiina Louhi:

Riitta Jalonen & Kristiina Louhi:

Aatos ja Sofian meri

[Aatos and Sofia’s sea]

Juba:

Juba:

Minerva. Alajuoksun kelluva pullukka

[Minerva. The floating dumpling of the Lower Reaches]

Riina Katajavuori & Salla Savolainen:

Riina Katajavuori & Salla Savolainen:

Pentti ja kitara

[Pentti and the guitar]

Malin Kivelä & Linda Bondestam:

Malin Kivelä & Linda Bondestam:

Bröderna Pixon och TV:ns hemtrevliga sken

[The Pixon brothers and the homely shimmer of the telly]

Jukka Laajarinne & Timo Mänttäri:

Jukka Laajarinne & Timo Mänttäri:

Isä vaihtaa vapaalle

[Dad takes time off]

Laura Lähteenmäki:

Laura Lähteenmäki:

Iskelmiä

[Hits]

Kreetta Onkeli:

Kreetta Onkeli:

Poika joka menetti muistinsa

[The boy who lost his memory]

Alexandra Salmela:

Alexandra Salmela:

Kirahviäiti ja muita hölmöjä aikuisia

[Giraffe mummy and other silly adults]

Katri Tapola & Karoliina Pertamo:

Katri Tapola & Karoliina Pertamo:

Toivon talvi

[Toivo’s winter]

Tags: books for young people, children's books, Finlandia Prize, literary prizes, publishing

No comments for this entry yet