Mad men

5 December 2013 | Non-fiction, Reviews

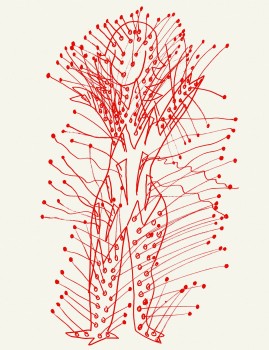

lllustration from the cover of Hulluuden historia

Hulluuden historia

[A history of madness]

Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2013. 456 pp.

ISBN 978-952-495-293-4

€39, hardback

The Hippocratic Oath’s principle, primum non nocere – ‘first, do no harm’ – has been particularly difficult to apply in practice for doctors who have devoted themselves to sicknesses of the soul.

The breaking with this principle is the first thing to strike the reader in Professor of Science and Ideas Petteri Pietikäinen’s book, Hulluuden historia, which is overflowing with ideas.

This could be due to the vast amount of information contained within the book, combined with its slightly chaotic structure. It skips between a chronological and thematic narratives, and the author’s own involvement in his text varies, meaning that the text itself swings between vigorously discursive, and something that is little more than a sluggish retelling. Taking in everything Pietikäinen wants to say is difficult; the reader inevitably begins to grope for exciting details, and there are of course plenty of those to be found.

The sad thing is that the development of mental health care has not advanced steadily at all from its dark and ignorant beginnings towards a brighter and more enlightened present. Setbacks, especially concerning patients’ safety, have been many. Even if we ignore centuries of exorcisms, abuse, and care in the form of incarceration, punishment, and physical punishment, the 20th century has a wealth of gruesome examples to offer.

One figure I was previously unaware of in the psychiatric abuse chamber of horrors was Doctor Henry Cotton (1876–1933), medical director of New Jersey State Hospital at Trenton. He believed that mental illnesses were caused by infections in different parts of the body – first he pulled out patients’ teeth, then he began to operate on their colons, appendices, peritoneums, and thyroid glands, all in the name of ridding them of their psychiatric symptoms. The death rate amongst his patients was high, not to mention all those who were crippled by the unnecessary operations, but no one seemed to have time to worry about this before Cotton fortunately died of a heart attack in 1933.

Another of the 20th century’s bizarre horror figures was Walter Freeman (1895–1972), the ‘ambassador of lobotomy’. He became famous for his brain surgery world record, 25 lobotomies carried out in just one working day. Thrusting a sharp instrument, reminiscent of a knitting needle with a handle into a patient’s eye socket, he then severed the nerve pathways behind the frontal lobe, which was believed to cure both depression and schizophrenia. His popularity began to fade after the mid-1950s, and this is now regarded to be dangerous abuse, rather than a medical procedure.

During the golden age of lobotomy, the operation was also carried out on children, in post-war Finland as well as in many other countries. But before we string ourselves up in shocked self-righteousness, we should reflect on Pietikäinen’s comment on the matter:

‘Permanent brain damage inflicted on children seems to be a particularly irresponsible medical procedure. In the light of what we nowadays know about on-going psychiatric medication for children, we don’t necessarily have reason to moralise over the treatments aimed at children in previous generations. Children have been subjected to, in very concrete terms, both the medical wisdom and stupidity of each era.’ Pietikäinen is probably referring here to today’s epidemic spread of ADHD diagnoses – for children who are hyperactive, inattentive, and have different kinds of learning difficulties – and the medication of these children with amphetamine based drugs such as Ritalin.

So, today we live in an age of psychiatric medication. Something that is shocking, and rarely talked about, is Pietikäinen’s observation that today’s psychosis medications cure the acute symptoms of illness in the short term, but may in the long term make people incapable of returning to a normal work and family life, even periodically. This train of thought is one that could have been developed even further.

Is this explosive growth we are seeing in psychiatric diagnoses and patients as a result of people becoming ill in a new way, in a new age? Or does it have more to do with diagnoses, rather than illnesses, sweeping through the psychiatric world like epidemics, created and shaped by the pharmaceutical industry’s powerful economic interests? Pietikäinen points out that corruption and manipulation of supposedly scientific research is a real risk.

As an entirety, this plentiful, sprawling book is interesting. The author says a certain amount about the Finnish situation, but I would have also liked to see a summary of the current state of Finnish mental health care, with examples.

Pietikäinen dismisses Sigmund Freud, narrow-mindedly in my opinion, as a ‘magician’ and a fake. I would like contest this point by reminding us of the sophisticated understanding and respect for each individual person’s own inner-world, formed by their personal history, which is fundamentally what psychoanalysis preaches. Freud’s teachings have made a vital contribution to the way in which we see childhood – as the vulnerable foundation for our individual existence – and the value of this insight is not something that 21st-century hecklers of psychoanalysis should be able to deny.

What’s more, many of the more far-fetched and unsuccessful experiments aimed at curing mental problems must be seen in the light of the rule of medical ethics, which sometimes conflicts with the edict of not harming. Faced with a person who is clearly suffering and causing great agony and worry around them, perhaps the doctor is forced to depart from the ‘do no harm’-principle in order to, with the best of intentions and more or less blindly, instead apply the pragmatic: ‘Do something!’

Translated by Claire Dickenson

No comments for this entry yet