Cut time, paste space

12 September 2013 | Articles, Non-fiction

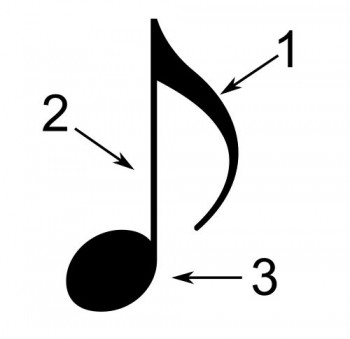

Back to basics. Parts of a musical note. Picture: Wikimedia

How different are the art of words and the art of sounds, author Teemu Manninen ponders, as he unexpectedly finds himself in the role of a musician in a performance. Time, space or both?

Some time ago I got the chance to participate in an unusual concert – as a performer: six players, myself included, were grouped around a table with a triangle in one hand and a glove in the other. Pieces of dry ice and a bucket of water were placed in front of each of us.

The performance began: we took a piece of dry ice and pressed it against the triangle. As the metal cooled, it burned through the ice, releasing gas, which in turn made the metal vibrate very fast. This produced a keening sound that filled the room.

After different lengths of time (dependent on the size of the piece of ice and its angle relative to the metal) the ‘instruments’ became sufficiently cooled to cease their ‘playing’, and we plunged them one after the other in the buckets to warm them up for another round.

Music is bound by time, and the essence of a piece of music, when performed, is in its evanescence, the transcience which gives it its value.

It is sometimes said that literature is an art bound by space: it manifests as a material object, a book, which exists regardless of when it is read. Transcience versus solidity: a big, slow, dumb object versus a lithe, adaptable process. Is that really so? Of course not.

Playing the dry ice piece, composed – or maybe rather invented – by an experimental American composer Liam Mooney, made me think about how I actually approach music and sound these days: as recordings which have a measurable length. And that which has length – a string of words, or a series of recorded sounds – can be cut. The cuttings can then be reattached together in a new order.

As my fingers cooled inside the glove holding the ice I realised that I had begun to think like this not because I am a musician, but because I am a writer. For me, cutting and pasting is not just a metaphor. The idea of building things out of bits like this has been made possible by contemporary word processing software. These programmes allow us to look at sequences of words and to reorder them at will.

But contemporary sound editing and digital recording software (Logic, Pro Tools or Cubase) work in the same way. They are always built on the same principle, to show a spatial representation of sound. Most often this is done by showing a series of ‘tracks’ on top of each other, with recorded sounds on each track represented by pictures of soundwaves running left to right. The soundwaves on these tracks, like words in paragraphs, can also be cut, pasted, deleted, mixed together, reordered and reconstituted.

Today’s music with its digital production technologies is nothing but the cutting and pasting of recombined recollections of recognisable choruses and chord progressions, and just like the familiar plots of detective novels or the stitched-together metaphors of poems, the cadences and hooks of the songs we know and love are all of this same cloth of collage. Writers and musicians both cut and paste, detach and reattach.

This is very different from pressing a piece of dry ice on a piece of metal – so much so that it surprised me how I had almost forgotten that music is not just recorded sound but also an acoustic artform, or an art of producing reverberations in objects inside resonant spaces. The keening of the metal under my fingers was distinct, I felt the sound. Of course a guitar trembles too, just like a piano or a drum; it’s just that I had forgotten they did so, because their sound had become too familiar to me as mere recordings, not as physical events.

Words can also be spoken, I remembered then, they can also exist in the transient, time-bound space between you and me. There is no essential difference, in that sense, between the art of words and the art of sounds. But there is a difference between recording and performing, between playback (or reading) and playing (or hearing): between presence and absence.

Some time in the future technology may evolve again and give us even stranger concrete metaphors to think and work with. Maybe we will then find that artforms will no longer be conceived of as inherently performative or plastic, bound by time or by space, but that a deeper schism will arise inside these fields previously unique unto themselves, a divide between recordable and nonrecordable arts, a division reminiscent, perhaps, of that between life as a series of unrepeatable events and the memories we have of those events, and the timeless monuments we build to commemorate their disappearance.

No comments for this entry yet