A rare bird from Fancyland

20 August 2013 | Reviews

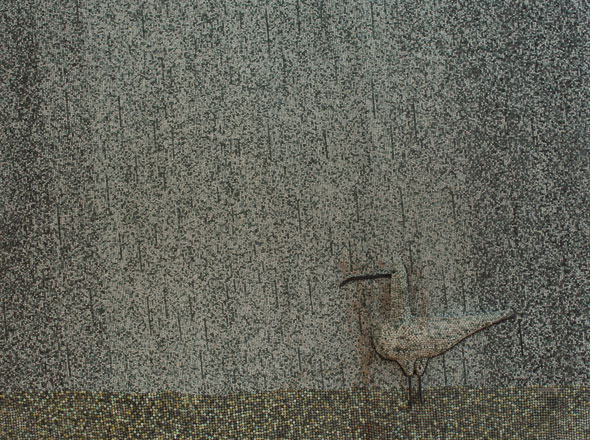

Bead-covered curlew, 1960. Height ca. 115 cm, Collection Kakkonen. Photo: Niclas Warius

Harri Kalha:

Birger Kaipiainen

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura (The Finnish Literature Society), 2013. 249 p., ill.

(Summaries in Swedish and English)

ISBN 978-952-222-457-6

€46, hardback

Ceramics confectioner. Degenerate aristocrat. Ornamental criminal. These epithets can be found in Birger Kaipiainen, a new, full-length study of the ceramic artist by art historian Harri Kalha.

Throughout his artistic career Birger Kaipiainen (1915–1988) worked with forms, subjects and methods that were unfamiliar in the field of traditional ceramics, at least in mid-20th-century Finland, and made use of fantasy and ornament. As a ‘porcelain painter’ he showed little interest in the technical challenges of clay – although in his ceramic creations Kaipiainen explored three-dimensional form, montage, colour, texture and the tactile dimensions of the medium.

Birger Kaipiainen in his Arabia workshop in the 1960s. Photo: Design Museum

His works included plaques, plates, bowls and sculptures, and his favourite subjects were female figures, flowers, plants and birds, with a particular emphasis on violets, swans and curlews. He used ceramic beads and shards of mirror to cover the surfaces of his creations, producing shapes and objects that surprised both critics and public.

Music and theatre were important to Kaipiainen. He once said: ‘I don’t know where Vivaldi ends and Botticelli begins,’ and, ‘Chopin loved violets, and I love Chopin.‘ During his long career he derived inspiration from Renaissance, Byzantine and Baroque art – and even a little from Pop. Artists whose universes resemble his include Botticelli, Chagall, de Chirico, Picasso, and de Kooning. He was a citizen not of Finland but of Fancyland; ‘beauty is pure fantasy,’ he claimed.

Kaipiainen graduated from the Ateneum art school in 1937. After trying scenography, he majored in pottery and then for the next half-century worked at the Arabia porcelain factory in Helsinki. He developed his career in the environment of industrial design, but never became a designer – he remained an artist, and was basically allowed to do what he liked. ‘Here [at Arabia] I’ve been able to grow like a weed,’ he said.

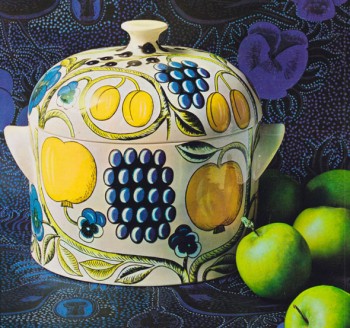

‘Paradise’, advertisement for tableware, 1970s

At Arabia Kaipiainen designed just a few series for mass production. One of them is his 1960s tableware entitled Paratiisi (‘Paradise’). This series was originally in production for a short time only, but in view of its great popularity was revived. Today it is a classic – as are his 1950s wallpaper designs featuring fantasy larks.

While the pre- and postwar decades of Finnish industrial design tended to concentrate on the unembellished functionality, muted colours and simple forms of mass production, Kaipiainen marched to his own drum: he was an oddball of his time. He ‘decorated’ everything he created.

But what the modernists saw as surface, was depth for Kaipiainen, says Harri Kalha; the central focus of Kaipiainen’s work lay not in ‘decoration‘ but in subjective pictorial narrative. ‘Whereas modernism wanted to remove the finesses (of handiwork and ornamentalism) associated with the surface, Kaipiainen held on to them more strongly than ever. [Kaipiainen] filled the surface […] out of sheer tactile drive,’ Kalha says in his analysis.

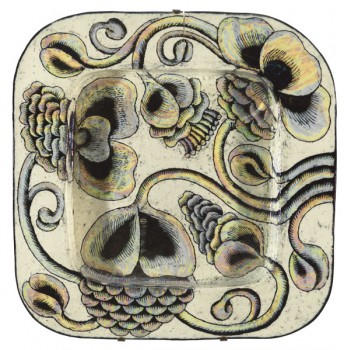

Wall plate, 1970s. Collection Kakkonen, photo: Niclas Warius

‘Kaipiainen balanced on the border between utter stylishness and excess, like a line dancer. He simply could not help himself, could not resist the enchantment of the surface, but surrendered to it time and again.’

Although Kaipiainen was not a ‘mainstream’ designer of the modernist wave, he did contribute to the international success and fame of Finnish industrial design in the postwar years. It was his original imagination that won him the Grand Prix at the 1951 Milan Triennale, awarded to him for his bead-covered bird sculptures.

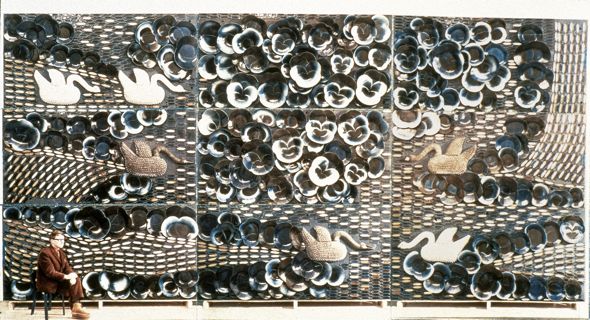

For the World Exhibition of 1967 in Montreal he created a huge bas-relief nine metres wide and four and a half metres high, entitled Orvokkimeri (‘The sea of violets’). With figures of flowers and white swans, it was created from around two million faience beads and pieces of mirror. It was indeed a sample of Finnish industrial art – which would gradually diminish in the shadow of industrial design and production.

‘The sea of violets’ (45,5 x 9 metres, World Exhibition, Montreal, 1967) and the artist

Some of Kaipiainen’s contemporaries did not, however, care to wander in his highly original Fancyland. Not only were his works felt to be too ‘decorative‘, they were also viewed as ‘un-Finnish’ and ‘exotic’ – or even arty-farty by those who preferred unembellished, ascetic and functional design. Kaipiainen’s work was associated with the words ‘aristocratic’, ‘elitist’ or even ‘decadent’. His unique creations were sometimes puzzlingly difficult to pigeonhole – not quite sculptures, but perhaps not ‘decorative objects‘ of industrial design either.

Wall plate with beads, 1970s. Collection Kakkonen, photo: Niclas Warius

So inspired is Harri Kalha by his subject that the book is a joy to read: he sets out to share his enthusiasm and knowledge with his reader – this is no dry art history written out of duty. Kalha immerses himself in the artist’s life and works, seeking philosophical, artistic, personal and psychoanalytical explanations as if he were an explorer on his way through a land previously uncharted – as indeed he is, as his is the first extensive study of Kaipiainen to be published.

The richly illustrated volume – designed by Anne Kaikkonen/ Timangi – is aptly clad in deep blue velvet, and in the front cover there is a flower-shaped opening through which the reader acquires a glimpse of a sea of violets.

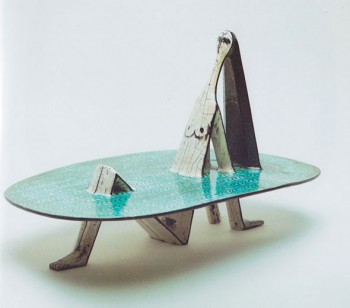

‘Bathing Susanna’, ca. 1957. Height ca. 30 cm. Rörstrand Museum, Sweden

Kylpevä Susanna (‘Bathing Susanna’, circa 1957) was created in Sweden, where Kaipiainen spent four years working at the Rörstrand porcelain factory. In Sweden his style was thought to be ‘exotic’ and ‘oriental’, and he himself was characterised as an ‘faience expressionist’. Kalha describes the work as follows:

‘Kaipiainen’s naiad bathes in waves of cleansing irony: the cardboard-like, angular, zigzag-shaped body makes at least this viewer smile; the knees above the surface, chastely pressed together, and the straight, wet boulder of black hair and the delicate craquelée of the skin delight. Kaipiainen’s ladies have wrinkles that are exquisitely dignified: even their skin is craquelée, expressing culture – once again we see how Kaipiainen consciously deviates from Nature: his naturism is a joyous celebration of antinaturalism.’ For Kaipiainen, Kalha explains, nature is always culture in disguise, unnatural.

As early as 1908 the Austrian architect Adolf Loos, an relentless advocate of austere modernism, proclaimed that ‘ornament is crime’, and ornaments ‘are fruitless’ by nature.

Kaipiainen, the ornament criminal, devoted his life to tending his wild, ecstatic gardens full of fantastic fruits and gigantic flowers. ‘In his role of gardener-pervert, Kaipiainen makes Nature laugh at herself,’ Kalha concludes.

Wall plate, ‘Two women’, ca. 1953. Collection Kakkonen, photo: Niclas Warius

Kaipiainen’s female figures are lyrical, dreamy, mystical, even surreal creatures. In a chapter entitled ‘Different from the rest’ Kalha – who specialises in gender studies – writes about the artist’s sexual ambivalence. ‘There can be no denying that his works express, to use the contemporary term, a queer identity.’ In the mid-20th century ‘free’ expression was, of course, impossible. ‘Romantic armour hides the erotic suggestion,’ he writes, exploring the significance of sublimation as an artistic method.

Throughout the book, Kalha’s interpretations provoke the reader to become more interested, to doubt, and to look at the works more closely.

Occasionally though, Kalha’s sprawling interpretations may become slightly cramped or repetitive. One of the book’s annoying omissions is that the captions to the illustrations lack information about the dimensions of the works. For example, the reader has no idea of the size of the impressive bas-relief Kuovi sateessa (‘Curlew in rain’: height one and a half, width two metres) – and what about ‘Bathing Susanna’, is she small, medium or large (height approximately 30 cm)?

‘Curlew in rain’, bas-relief (150 cm x 200 cm, ca. 1970). Collection Kakkonen, photo: Niclas Warius

It would also have been interesting to have records (or even estimates) of the quantities of serial plates by Kaipiainen that Arabia produced in the 1970s and 1980s, as these are still on constant sale, bought at auctions and in design shops.

Kaipiainen was neither a designer nor a decorator, but a decorative artist, and his oeuvre was in fact an antithesis of design; Kalha says that ‘from the viewpoint of design [it] is useless, and from the viewpoint of art unclean: contaminated by home, handiwork and the industrial sphere.‘

Design or decoration, that may be the question – but what really matters is that this rare bird flies on for the delight of future fans of fantasy.

Wall plate ‘Violet tree’, 1960s. Collection Kakkonen, photo: Niclas Warius

The exhibition ‘Aesthete extraordinaire’ at EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art, curated by Harri Kalha, presents an extensive collection of Kaipiainen’s work until 12 January 2014.The exhibition is based on works from the Kyösti Kakkonen Art Collection. Birger Kaipiainen has been published as a joint project of the Finnish Literature Society and EMMA.

Tags: art, biography, cultural history, design, design history

No comments for this entry yet