Fatherlands, mother tongues?

12 April 2013 | Letter from the Editors

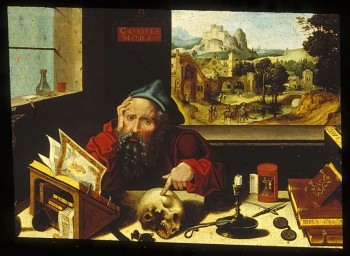

Patron saint of translators: St Jerome (d. 420), translating the Bible into Latin. Pieter Coecke van Aelst, ca 1530. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Photo: Wikipedia

Finnish is spoken mostly in Finland, whereas English is spoken everywhere. A Finnish writer, however, doesn’t necessarily write in any of Finland’s three national languages (Finnish, Swedish and Sámi).

What is a Finnish book, then – and (something of particular interest to us here at the Books from Finland offices) is it the same thing as a book from Finland? Let’s take a look at a few examples of how languages – and fatherlands – fluctuate.

Hannu Rajaniemi has Finnish as his mother tongue, but has written two sci-fi novels in English, which were published in England. A Doctor in Physics specialising in string theory, Rajaniemi works at Edinburgh University and lives in Scotland. His books have been translated into Finnish; the second one, The Fractal Prince / Fraktaaliruhtinas (2012) was in March 2013 on fifth place on the list of the best-selling books in Finland. (Here, a sample from his first book, The Quantum Thief, 2011, Gollancz.)

Emmi Itäranta, a Finn who lives in Canterbury, England, published her first novel, Teemestarin tarina (‘The tea master’s book’, Teos, 2012), in Finland. She rewrote it in English and it will be published as Memory of Water in England, the United States and Australia (HarperCollins Voyager) in 2014. Translations into six other languages will follow.

These, however, are relatively simple cases; a more complicated one is Hassan Blasim, an Iraqi scriptwriter, producer and author who fled from Iraq due to the controversial views expressed in his work. Blasim moved to Finland in 2004; his two collections of short stories, written in his native Arabic, were translated into English and published in the UK. The Guardian newspaper’s reviewer called him ‘the best writer of Iraqi fiction’, and his latest book, The Iraqi Christ, won him British PEN’s Writers in Translation prize last year. His collection of short stories, The Madman of Freedom Square, was published in Finnish last year (translated from Arabic by Sampsa Peltonen).

In Finland, Blasim is currently regarded as in some sense a ‘Finnish author’; he was one of 47 authors who were awarded a novel-writing grant by the Finnish National Council for Literature in 2013.

Various private institutions and foundations also grant funds for promoting ‘Finnish cultural life’; one of the wealthiest is Svenska kulturfonden (Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland, est. 1908) whose mission is ‘to support and strengthen the culture and education of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland’, for which it contributes around 33 million euros annually. Suomen Kulttuurirahasto (the Finnish Cultural Foundation, est. 1937) gave 21,3 million euros this year.

The foundations don’t seem to bother sorting applicants according to language or nationality: what interests them, in principle, is the potential impact of the project on ‘Finnish cultural life’, as well as the merits of the applicant.

According to its rules, the Union of Finnish Writers, Suomen kirjailijaliitto, accepts as members writers who have published two original works of fiction written in Finnish, and the same principle is applied in the Swedish-language association, Finlands Svenska Författareförening. For these guardians of the privileges of the Finnish authors, no other tool is acceptable for a ‘Finnish writer’ to work with than Finnish or Swedish.

So Finland finds itself addressing the same question that has long confronted the big languages – English and Spanish in particular – whose literature exceeds that written by natives in their native languages. It would be hard to argue that those cultures were not enriched by the work of, for example, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie or Khaled Hosseini and Javier Marías or Roberto Bolaño.

On the subject of which nationality or which language any given author writes in, it’s time to relax, read, and enjoy.

Tags: identity, language, media, publishing, translation, writing

No comments for this entry yet