Happy days, sad days

28 February 2013 | Reviews

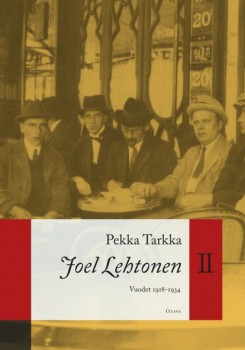

Pekka Tarkka

Pekka Tarkka

Joel Lehtonen II. Vuodet 1918–1934

[Joel Lehtonen II. The years 1918–1934]

Helsinki: Otava, 2012. 591 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-1-25924-4

€38.50, hardback

A well-meaning bookseller’s idealism, inspired by Tolstoyan ideology, is brought crashing down by the laziness and ingratitude of the man hired to look after his estate: conflicts between the bourgeoisie and the ‘ordinary folk’ are played out in heart of the Finnish lakeside summer idyll in Savo province.

Taking place within a single day, the novel Putkinotko (an invented, onomatopoetic place name: ‘Hogweed Hollow’) is one of the most important classics of Finnish literature. Putkinotko was also the title of a series (1917–1920) of three prose works – two novels and a collection of short stories – sharing many of the same characters [here, a translation of ‘A happy day’ from Kuolleet omenapuut, ‘Dead apple trees’, 1918] .

In 1905 Joel Lehtonen bought a farmstead in Savo which he named Putkinotko: it became the place of inspiration for his writing. With an output that is both extensive and somewhat uneven, the reputation of Joel Lehtonen (1881–1934) rests largely on the merits of his Putkinotko, written between 1917 and 1920.

Originally published in two volumes, this massive novel is, on the one hand, a chronicle of the tense relationship between Lehtonen (who had himself risen from the ranks of the ‘ordinary folk’) and his half brother and, in more general terms, an exploration of the question of land ownership, which was the subject of heated social debate at the time the novel was written.

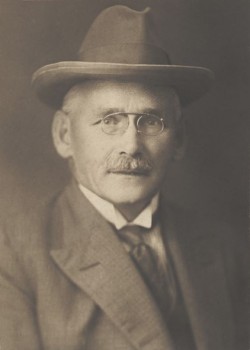

Joel Lehtonen, 1931. Photo: Otava

Combining elements of naturalist, humorist and lyrical narrative, Putkinotko reinvented the image of ‘the people’ which had dominated Finnish prose since the 1880s – and which re-emerged in the 1950s and 1960s with Väinö Linna’s expansive novels (Täällä Pohjantähden alla, I-III, ‘Here under the North Star’) on national themes.

The sheer modernity of Putkinotko was something new in Finland, and at first the novel was received with confusion and scepticism – in contrast to the work’s reception in Finland’s neighbouring countries when the novel appeared in translation.

The journalist, critic and writer Pekka Tarkka has undertaken the arduous task of researching the life and works of Joel Lehtonen. His doctoral thesis (published in 1977) examined the cast of characters in Putkinotko.

In 2009 Tarkka published the first part of his biography of Joel Lehtonen, concentrating on the first 36 years of the author’s life and on the literary output from the earlier part of his career. The second part of the biography (2012) continues from the Finnish Civil War of 1918 until 1934, when Lehtonen tragically took his own life.

The author’s life was filled with illness, bouts of depression and unhappy relationships. Indeed, Lehtonen’s life got off to a rather traumatic start: he had no knowledge of his father’s identity; his mother was a homeless woman who abandoned her six-month-old son by the side of a road. The boy who was eventually to become an author spent his first years in an orphanage and between numerous squalid foster homes. But his last foster mother was the wife of a priest, and it was from the Wallenius’s bourgeois household that Lehtonen was able to begin his education and undertake his entrance into ‘society’.

Even in Tarkka’s biography, it is the Putkinotko trilogy that receives the most attention. Generally considered of lesser artistic value, Lehtonen’s earlier works, displaying the influence of Nietzsche and foreshadowing the advent of existentialism, are described by Tarkka in traditional manner as written in a neo-romantic vein, and he takes pains to link them to more general trends in the Nordic artistic life of the day. In this way he challenges the notion, common to much previous research into Lehtonen’s work, that the primary context for Lehtonen’s earlier works was that of European decadence.

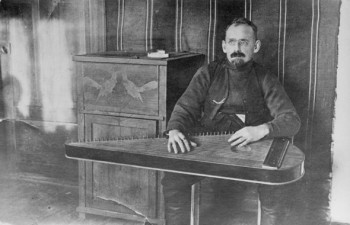

Farewell with a kantele: the author sold his Putkinotko farmstead in 1922. Photo: Aleksander Sihvonen, 1921 (Otava archive)

In the satirical novels that follow Putkinotko, Lehtonen’s laughter turns increasingly bitter as social conditions and the author’s health continued to worsen. Rakastunut rampa (‘The infatuated cripple’, 1922) is a grotesquely exaggerated self-portrait set against the social background of the Finnish Civil War of 1918. Henkien taistelu (‘The battle of souls’, 1933) is a critical take on the violent rise of the radical right wing in Finland and throughout Europe.

Lehtonen also published poetry; his final work was the poetry collection Hyvästijättö Lintukodolle (‘Farewell, the Haven’, 1934) in which Lehtonen explores the idea of approaching death and gives a melancholy appraisal of the life he has lived, a life filled with much hardship and much chasing after the wind.

As a researcher and biographer, Tarkka does not rigorously follow any particular method but writes rather freely following his own train of thoughts. Lehtonen’s friendships, relationships with women, financial affairs, his working relationship with publishers, his ever-changing apartments and summer cottages, trips abroad and illnesses are comprehensively outlined. Typically of the biographical genre, the author’s output is contextualised in terms of his own life, while the role of the Western literary tradition remains secondary. Influences and points of comparison are sought in paintings and music, and the relation of Lehtonen’s works to the contemporary social climate and literary works of the day is examined to a certain extent.

Tarkka is particularly interested in Lehtonen’s gallery of colourful characters, and much of his research concentrates on pinpointing their real-life inspirations. Tarkka’s extensive biography references Lehtonen’s works in fine detail; almost without our noticing, he imbues his commentary with observations that can be interpreted in numerous ways.

Translated by David Hackston

Tags: biography, literary history, novel, short story

No comments for this entry yet