Pen to paper

25 October 2012 | Articles, Non-fiction

Writing is ancient: the act of taking a stylus, a quill or a pen into one’s hand still feels powerful. Will we find a way of scrawling in space, to mark our individuality, wonders Teemu Manninen

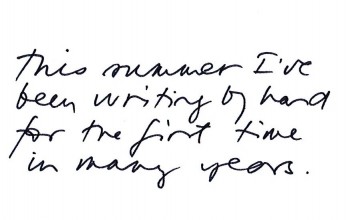

It was my vacation, and I wanted to catch up on some fun writing projects, but because I didn’t want to depend on my devices (would we have wifi? would the batteries last?) or carry around too much extra stuff I bought a red notebook and wrote in black ink on white paper while sitting in cafes and restaurants with my wife.

Writing by hand got me – surprise – to thinking about handwriting in general. Etymologically, ‘writing’, from Old English writan, means scratching, drawing, tearing. In the original Hebrew, God does not simply fashion humans out of clay, he writes them: his word is his image, giving life to the letter of his meaning, the human being.

Writing is violence. It brings about vivid change in the matter of the world: in the age of clay tablets, the stylus was a carving instrument. During the age of ink, cutting the tip of the quill was, if we believe the early Renaissance manuals of handwriting, as precise and violent an act as cutting someone’s head off.

Uniform handwriting is a staple of civilised societies: you learn to read and write the same way you learn that men wear pants and women skirts and God is good and the King is to be obeyed – or, at least, you used to, until things changed and we dethroned the King, killed God and started wearing unisex clothing and, in conjunction, developed unique and individual hands.

I myself have changed my handwriting style consciously three times in my life, because I felt that the way I wrote did not reflect who I was as a person. Why?

It might be argued that this evolution in the idea of handwriting begins sometime in the latter early modern age, when the idea of the genius author was invented. At the same time our attitude towards the writer’s hand changed: we started to collect their manuscripts, to prize them as unique artifacts which needed to be studied, as if by decoding the qualities of Wordsworth’s, Stendhal’s, Flaubert’s or Joyce’s hand we could somehow reveal the individual nature of these writers.

But every style of handwriting, be it institutional or personal, also contains meanings that are independent of what is written or who is writing, just like styles of clothing or tastes in food are meaningful apart from the purely pragmatic functions of fabric to clothe our naked bodies or of foodstuffs to feed our hungry mouths.

For example, cursive script, which became the basis of our modern hand, was developed by Italian Renaissance humanists in order to make writing faster by not having to lift the pen off the paper. The loops and curves which were needed to accomplish this also gave cursive script an aesthetically pleasing quality. Because of this ‘the Italian hand’ was adopted for intimate letter-writing by the nobility, but the accidental aesthetic features also developed into the flourishes and frills that are still the central features of fine calligraphy.

I wonder if something so culturally complex and nuanced as handwriting will ever develop in the digital future. All we have is typewriting: a series of gestures that are always the same – taps on keys or surfaces, everyone exactly alike. There doesn’t even seem to be any role for the signature these days, since our credit card PIN is replacing it everywhere we turn.

Will we ever again invent a way to mark our individuality somehow with a characteristically performative scrawl in space, a material signifier of who we are and what our deepest self is like, or should such an idea be forgotten as just a construct, a phase? I sometimes think that the eccentricities of language on the web are meant to compensate for the sterility of the medium somehow, as if all the acronyms, the shortened, coded phrases, intentional grammatical and stylistic errors are the cursive of our time, the flourishes of individual style.

Then again, all of this might just be empty rhetoric, since we might, from the point of view of history, breeze past this cold age of glass screens just as easily as we did the millenia of clay tablets and the centuries of quills which came before it. After all, writing is ancient, it transcends its medium. That is why it is so powerful a tool, and that is why we are still a culture of the idea of the book.

No comments for this entry yet