Nationalism in war and peace

3 May 2012 | Reviews

House of words: the Finnish Literature Society building in Helsinki. Architect Sebastian Gripenberg, 1890. Watercolour by an unknown Russian artist, 1890s

Kai Häggman

Sanojen talossa. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura 1890-luvulta talvisotaan

[In the house of words. The Finnish Literature Society from the 1890s to the Winter War]

Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2012. 582 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-328-9

€54, hardback

The Finnish Literature Society has, throughout its history, played a multiplicity of roles: fiction publisher, research institute specialising in folklore studies, organiser of mass campaigns in support of national projects, literary gatekeeper, learned society, controller of language development.

The priorities of these areas of interest have changed from decade to decade, so Kai Häggman has taken on an exceptionally difficult subject to describe. He has, however, succeeded brilliantly in gathering the different threads together, using as as lowest common denominator the ideas of nationalism and nation whose role in global modernisation and European history have been studied, among others, by the British historians Ernest Gellner and Eric Hobsbawm.

They drew attention to the nationalism born in the backwaters of the 19th-century superpowers of Eastern Europe, which was a springboard to the birth of nation states such as the Czech republic and Slovakia. Similar historical developents were evident in Hungary and Estonia, which were, as Finnic peoples, close to the heart of the Finnish Literature Society. In these countries, the local folklore provided the foundation for national identity.

The nationalist phenomenon offers Häggman an opportunity for international comparison. He draws parallels with, for example, Ireland; Séamus Ó Duilearga, an eminent folklorist active in the Irish nationalist movement, visited and learned from the Finnish Literature Society. In Ireland, of course, the original native language did not achieve the desired position of power, unlike in Finland, where Finnish supplanted Swedish as the language of government, commerce and education in the early 20th century.

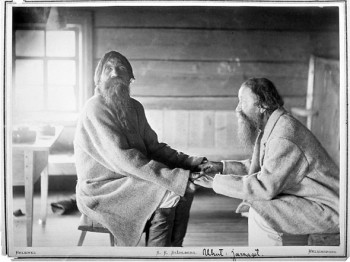

Two rune-singers: the brothers Paavila and Triihvo Jamanen reciting in Uhtua, 1894. Their father had been recorded by Elias Lönnrot, compiler of the Kalevala

The Finnish Literature Society entered the service of the nationalist movement in Finland, for it needed words as well as deeds. The promotion of the young written language became one of the Society’s most important priorities. It was activity led the cultural elite, but the Society was able to mobilise, if not the entire nation, then at least the Finnish-speaking middle strata. It organised campaigns in which enlightened members of the nation participated enthusiastically by sending in rapidly disappearing memoirs and vocabulary. By 1908 the Society’s ‘word bank’ already contained as many as half a million word-slips. One enthusiastic Fennomane calculated that if they were piled up the result would be a tower higher than Helsinki’s cathedral. Häggman is unable to restrain himself from poking a little gentle fun at this passion for collecting, with which the Society’s other activities could not always keep up.

Häggman draws attention to the conflict between traditional and modern values that characterised the nationalist movement. Although nationalism in theory favoured and in practice constructed a modern nation state and looked to the future, the recording of vanishing native dialects and traditions focused attention on the past. The traditionalist folklore-gatherers often took a dubious view of modernisation because it rode rough-shod over the old culture and standardised language. The Society debated whether its direction should be sought in the past or the present. The answer was ‘both’; the Society was like an ‘aged mother’ who lavished some care on everything and was the supporter of many different nationalist projects.

Kalevala in English: W.F. Kirby, butterfly-scholar and linguistic genius, translated the Kalevala into English in 1907; J.R.R. Tolkien, among others, was greatly impressed

As a promoter and defender of the developing literary and administrative language, the Finnish Literature Society has, over the years, played an important role. In this respect Häggman dubs it the state publisher, for the government support it has received for its various literary projects have been nothing if not substantial. During the period of Russian rule, in particular, it had close ties to the Senate, and its leaders were among the members of the compliant conservative grouping who remained loyal to St Petersburg even during what is known as the period of Russification. The constitutionalist liberals were, indeed, most disapproving when, in 1902 and in the midst of an anti-Russian rebellion, the Society published a Finnish-Russian dictionary of a thousand pages.

The links between state and Society remained close after Finland gained its independence. The Finnish government supported the most important of the dictionaries published by the Society, Nykysuomen sanakirja (‘A dictionary of contemporary Finnish’), work on which began in 1929; it was eventually published in the 1950s. It ranks with the great dictionaries of other countries in offering accurate knowledge about the Finnish words that are used in the living language. In its concern for the rules and discipline of standard Finnish, the Society took the academies of France and Sweden as its examples. The elite that oversaw correct use of language became quite popular among the masses, as ordinary people concerned about points of grammar were happy to turn to the Language Office for help.

Everywhere, folklore has been a source of power for nationalism, a pillar of national identity. In charting the role of the Society in 1893, it was noted that Finnish folk poetry was superior in both quantity and quality to that of other countries. The Society understood that the study of folk poetry could not be based entirely on the Kalevala, as collected and put together by Elias Lönnrot (the first version appeared in 1836); the starting point had to be the original folk poems that were held in the Folk Poetry Archive, the Society’s treasure chest. Over the years, a 33-volume work entitled Suomen Kansan Vanhat Runot (‘The ancient poetry of the Finnish people’) was published, containing around 100,000 different poem texts.

The comparative folk-poetry scholarship championed by one of the Society’s important figures, Kaarle Krohn, emphasised the international nature of the discipline. In his doctoral thesis, Krohn labelled the ‘patriotic perspective’ that had been handed down from the time of the brothers Grimm, in which peoples sought their history and soul from their old poems, as old-fashioned. Krohn’s folkoristics played by super-national rules: in 1907 Krohn and the Dane Axel Olrik founded an international network of scholars whose series of publications, Folklore Fellows, belonged to the elite of humanist disciplines. A typology of folk tales published in the series by Krohn’s student Antti Aarne became an international classic.

Finland’s independence, gained in 1917, was followed by a change in the nation’s mood; Häggman follows this in dividing his book chronologically in two. At first, Finnish nationalism was a belief in the power of the word and the spirit, but in the 1920s and 1930s folk poetry was interpreted ‘historically and militarily’. Already in the 19th century national romantics had travelled beyond the eastern border of the Grand Duchy studying the lives of the fragmented Finnic tribes that lived there and dreaming of reuniting them.

Always vigilant: the Society’s civil defence group on the roof of the building in 1939. In the background, Helsinki's Orthodox Cathedral

It was not a big step from this cultivation of kinship and cultural links to the political idea of a Greater Finland. Even as cool-headed a scholar as Kaarle Krohn had ventured to suggest that while the Kalevala had earlier been read as an epic of peaceful times and a story about the power of the word, now it ‘echoed with the din of warlike sea-voyagers, glittered with golden swords’. He advised the young people of the newly independent country to view themselves as folklore heroes.

The Second World War cured Finland of its nationalist megalomania; the young men of the 1930s were forced to show their military capabilities in war against the attacks of the Soviet Union. Häggman will address the post-war history of the Finnish Literature Society in the third volume of his work, to be published in 2014.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Published earlier:

Irma Sulkunen: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura 1831–1892 (‘The Finnish Literature Society 1831–1892’, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 2004. Reviewed by Outi Lehtipuro in Books from Finland 3/ 2004.

Tags: cultural history, Finnish history, Finnish society, literary history, politics, publishing

No comments for this entry yet