Archive for February, 2012

Cityscapes

23 February 2012 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Photographer Stefan Bremer’s home town, Helsinki, provides endless inspiration, material and atmospheric. For forty years Bremer has been recording views of the maritime city, its changing seasons, its cultural events, its people. These images are from his new book – entitled, simply, Helsinki (Teos, 2012)

City kids: day-care outing in Töölönlahti park. Photo: Stefan Bremer, 2010

When I was a child, Helsinki seemed to me a grey and sad town. Stooping, quiet people walked its broad streets. The colours of the houses had been darkened by coal smoke over the years, and new buildings were coated a depressing grey.

A lot has since changed. Today, Helsinki is younger than it was in my youth. More…

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin [C.L. Engel. Home in Helsinki, heart in Berlin]

23 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin

C.L. Engel. Koti Helsingissä, sydän Berliinissä. C.L. Engel. Hemmet i Helsingfors, hjärtat i Berlin

[C.L. Engel. Home in Helsinki, heart in Berlin]

Tekstit [Texts by]: Matti Klinge, Salla Elo, Eeva Ruoff

Valokuvat [Photography]: Taavetti Alin & Risto Törrö

Översättning [Translations from Finnish into Swedish]: Ulla Pedersen Estberg

Helsingfors: Schildts, 2012. 140 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-50-2183-0

€ 31.50, hardback

The life and works of the German architect Carl Ludvig Engel (1778–1840) are portrayed in four articles by specialists in Finnish history, the history of Helsinki and the history of gardens. Engel spent almost 24 years in Helsinki, transforming it with his architectural designs. For eleven of those years, he and his family lived in a house surrounded by a large garden, both of them his own creations. Looking for work, the young Engel finally found it in the tiny northern town that was pronounced the new capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1812 – both Tsar Alexander I and his successor, Nikolai I, favoured him. From 1816 onwards he designed more than twenty neo-classical buildings, among them nationally important landmarks: the Cathedral, the City Hall, the National Library and the University. Despite his mostly rewarding job as a highly regarded city planner, Engel found Helsinki cold, small and quiet, and he constantly longed for his native Berlin, which he never saw again. However, his flourishing garden gave him great pleasure. Richly illustrated with photographs, the book gives the reader an thorough and interesting picture of this city-changing man and his era.

Life is

16 February 2012 | Letter from the Editors

Helsinki silhouette. Photo: Valtteri Hirvonen, Eriksson&Company / World Design Capital Helsinki, 2011

Where is Books from Finland located?

In the old days, the answer was simple, although not unambiguous. Books came from its office in central Helsinki; it was written in various locations in Finland and abroad, and translated mainly in England and the United States; and it was published in the small town of Vammala, about 200 kilometres north of Helsinki.

It spread, in multiple paper copies, to readers throughout the world, to find its place on desks, on bedside tables, in briefcases and handbags, propping up table-legs or holding doors open – in London, England, Connecticut, New England, with a few in Paris, France, and Paris, Texas, maybe. More…

Art or politics?

16 February 2012 | This 'n' that

You’re going about your business in Helsinki Railway Station on a cold winter’s day — waiting for your train, buying tickets or newspapers or just taking short-cut through the building to keep warm – when suddenly the bloke next to you bursts into song. And not just him: along with a couple of dozen others, he makes the air ring with the patriotic song Finlandia, sung in harmony and perfectly in tune. (The video can be viewed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wO63xt2jWtc) More…

Wo/men at war

9 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

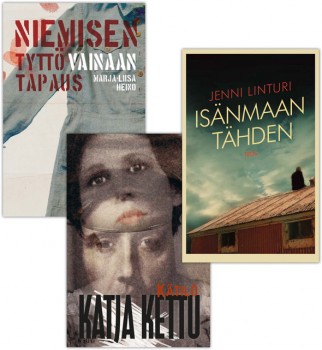

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

The wars that Finland fought 70 years and a couple of generations ago continue to be a subject of fiction. Last year saw the appearance of three novels set during the years of the Continuation War (1941–44), written by Marja-Liisa Heino, Katja Kettu and Jenni Linturi

In reviews of Finnish books published this past autumn, young women writers’ portraits of war were pigeonholed time and again as a ‘category’ of their own. This gendered observation has been a source of annoyance to the writers themselves.

Jenni Linturi, for instance, refused to ruminate on the impact of her sex on her debut novel Isänmaan tähden (‘For the fatherland’, Teos), which describes the war through the Waffen-SS Finnish volunteer units and the men who joined them [1,200 Finnish soldiers were recruited in 1941, and they formed a battalion, Finnische Freiwilligen Battaillon der Waffen-SS].

The work received a well-deserved Finlandia Prize nomination. Tiring of questions from the press about ‘young women and war’, Linturi (born 1979) was moved to speculate that some critics’ praise had been misapplied due to her sex. The situation is an apt reflection of the waves of modern feminism and the reasoning of the so-called third generation of feminists, who reject gender-limited points of view on principle. More…

Allan Tiitta: Sinisten maisemien mies. J.G. Granön tutkijantie 1882–1956 [The man of blue landscapes. A biography of J.G. Granö, 1882–1956]

9 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Sinisten maisemien mies. J.G. Granön tutkijantie 1882–1956

Sinisten maisemien mies. J.G. Granön tutkijantie 1882–1956

[The man of blue landscapes. A biography of J.G. Granö, 1882–1956]

Kuvatomittaja [Picture editor]: Taneli Eskola

Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society, 2011. 541 p., ill.

ISBN 978-952-222-292-3

€ 44, hardback

The man of blue landscapes describes the life and work of the Finnish geographer Johannes Gabriel Granö (1882–1956), whose career also reflected Finland’s development as a modern state. Granö was a scientific explorer, writer, a pioneer of Finnish photographic art and a professor of geography at the universities of Tartu (Estonia), Helsinki and Turku. In Estonia he applied scientific method to the study of local history and from Tartu brought the tradition of urban research. Granö spent much of his youth in Omsk in western Siberia, where his father worked as a priest among displaced and deported Finns and Estonians. From 1906 to 1916 Granö made an expedition to Mongolia and the Altai mountains, but his fieldwork remained unfinished when the 1917 revolution broke out; the area was then closed to Western scholars for 70 years. Among Granö’s most important works are the classic travel book Altai, vaellusvuosina nähtyä ja elettyä (‘The Altai, seen and experienced during my years of travel’, 1921) and his methodological masterpiece Puhdas maantiede (‘Pure geography’, 1930). In it Granö outlined a theory of landscapes, and the book was a pioneering work ahead of its time: landscape was examined in terms of the relation between human beings and their environment, as the sum of all the senses.

Translated by David McDuff

The novel that won: the Runeberg Prize 2012

9 February 2012 | In the news

Katja Kettu. Photo: WSOY

The Runeberg Prize for fiction, awarded this year for the twenty-sixth time, went to Katja Kettu for her third novel, Kätilö (‘The midwife’, WSOY).

Kettu (born 1978) is a writer and director of animated films. The prize, worth €10,000, was awarded on 5 February – the birthday of the poet J.L Runeberg (1804–1877) – in the southern Finnish city of Porvoo.

The jury – representing the prize’s founders, the Uusimaa newspaper, the city of Porvoo, both the Finnish and Finland-Swedish writers’ associations and the Finnish Critics’ Association – chose the winner from a shortlist of eight books. The jury was particularly impressed by the rich language of Kettu’s novel, set in the Lapp War of 1944–45, and the colourful portrayal of the characters.

The other seven finalists were a collection of essays and poems, Magnetmemoarerna, by Ralf Andtbacka (‘Magnet memoirs’, Ellips), the novel Tusenblad, en kvinna som snubblar (‘Millefeuille, the woman who stumbles’, Schildts), the novel Gisellen kuolema (‘Giselle’s death’, Robustos) by Siiri Eloranta, two collections of poems, Aallonmurtaja (‘The breakwater’, Otava) by Pauliina Haasjoki and De bronsblå solarna (‘The bronze-blue suns’, Söderströms) by Kurt Högnäs, a collection of short stories by Joni Pyysalo, entitled Ja muita novelleja (‘And other stories’, WSOY) and the novel Paljain käsin (‘With bare hands’, Gummerus) by Essi Tammimaa.

Panem et circenses?

2 February 2012 | This 'n' that

The Guggenheim Foundation's global network of museums

What does Helsinki need? Bread and circuses, yes, but at what cost the latter?

In January – after a study that cost the Finns a couple of million euros – the Salomon R. Guggenheim Foundation (est. 1937) indicated that it was favourably inclined toward the construction of a new art museum, bearing its name, in Helsinki. The leaders of Helsinki city council are aiming to make a positive decision as soon as possible.

The cost of the building, whose site adjoins the Presidential Palace in central Helsinki, is estimated at 130–140 million euros, with design costs of about 11 million euros. Unlike in the case of Berlin, no existing building is considered suitable; instead, an architectural dream must be realised, with plenty of wow-factor.

Its mere maintenance costs will be around 14.5 million euros a year. It has been estimated that the Helsinki Guggenheim’s income could be 7.7 million a year. In addition, a 20-year Guggenheim licence costs 24.6 million euros.

The project has provoked widely differing reactions. Proponents of the project believe that the Guggenheim brand would bring thousands of new visitors to Helsinki and that half a million people would visit it each year. Opponents doubt this, speak of a ‘Guggenburger’ franchising concept and of the fact that not even the existing art museums of Helsinki are particularly crowded.

The odd thing is, however, that the basic demographic differences between Helsinki and, say, Bilbao – where the Guggenheim museum has been a big success – are constantly ignored in the discussions: the population of Spain is almost 50 million and another 50 million visitors go there every year, while the corresponding figures for this most northerly part of Europe are five million inhabitants and visitors.

In Bilbao, moreover, there was no museum of contemporary art before the advent of the Guggenheim; Helsinki, on the other hand, opened Kiasma, a new museum of contemporary art (165,000 visitors in 2010) in 1998 and the neighbouring city of Espoo its Emma museum of modern art (82,000 visitors in 2010) in 2006.

Economic prospects on any level now offer little hope. The Finnish government, in the shape of the ministry of culture, has just cut grants to state-aided museums by three million euros – the Museum of Cultures in Helsinki, for example, is closing its doors, and some 40 of the museum staff elsewhere will be sacked. The government is not promising any money to the Guggenheim.

How, then, to fund an annual deficit of 7 million euros? Finland does not have a great supply of art-minded millionaire sponsors, and no one has so far made any concrete offers on how to fund this project.

The Guggenheim Foundation itself is not taking any financial risks with this project. Neither has it announced in any detail what sort of art will feature in the museum’s temporary exhibitions.

People who live in the city are more preoccupied with, for example, the shortcomings of the health services: there are waiting lists for everything, often of many weeks, and the old university children’s hospital has outgrown its present space. There are cuts and shrinkages yet to come in the spending structure of the country as a whole and of Helsinki – civil servants themselves estimate that the city’s budget is not sufficient to cover even the upkeep of basic services.

To judge by the public debate, the deep ranks of Helsinki taxpayers do not want a new monument, one for which it will be necessary to pay – in addition to maintenance – more than a million euros a year to an American brand for the mere use of its name, for more than 20 years.

Do the people of Helsinki wish to begin to pay additional taxes for the revival, yet again, of the age-old dream of guaranteeing Finland ‘a place on the world map’, in a situation where economic difficulties are a matter of everyday life for increasing numbers of them? (We believe, incidentally, that Finland already has an appropriate place on the world map.) Will their opinion be asked, or heard?

Horse sense

2 February 2012 | Essays, Non-fiction

The eye that sees. Photo: Rauno Koitermaa

In this essay Katri Mehto ponders the enigma of the horse: it is an animal that will consent to serve humans, but is there something else about it that we should know?

A person should meet at least one horse a week to understand something. Dogs help, too, but they have a tendency to lose their essence through constant fussing. People who work with horses often also have a dog or two in tow. They patter around the edge of the riding track sniffing at the manure while their master or mistress on the horse draws loops and arcs in the sand. That is a person surrounded by loyalty.

But a horse has more characteristics that remind one of a cat. A dog wants to serve people, play with humans – demands it, in fact. With a dog, a person is in a co-dependent relationship, where the dog is constantly asking ‘Are we still US?’ More…

A Finnish comics award

2 February 2012 | In the news

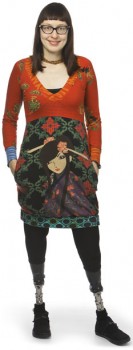

Kaisa Leka

Suomen sarjakuvaseura (The Finnish Comics Society) has awarded its Puupäähattu Award 2012 to the graphic artist and illustrator Kaisa Leka.

The prize is not money but a honorary hat, and is named after a classic Finnish cartoon character, Pekka Puupää (‘Pete Blockhead’), created by Ola Fogelberg and his daughter Toto. The Puupää comic books were published between 1925 and 1975, and some of the stories were made into film.

Leka describes herself as a mouse named Kaisa. Both of her legs have been replaced with steel prostheses, and she has featured disability in her comics book, for example in I Am Not These Feet.

Artificial limbs haven’t stopped her from cycling, for example, from Finland to Nice in France; she has described this tour in her book entitled Tour d’Europe.

The award: Puupäähattu (‘Blockhead hat’)

(See a video of Kaisa cycling, by Lina Jelanski.)

Johanna Sinisalo: Enkelten verta [Angels’ blood]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Enkelten verta

Enkelten verta

[Angels’ blood]

Helsinki: Teos, 2011. 274 p.

ISBN 978-951-851-414-8

€ 32, hardback

The literary career of Johanna Sinisalo (born 1958) has embraced fiction, drama, sci-fi and children’s books. Her 2000 Finlandia Fiction Prize-winning fantasy novel Ennen päivänlaskua ei voi and the novel Linnunaivot (2008) have been published in English as Not before Sundown and Birdbrain respectively. In this new novel, set in the near future, the central role is played by bees: widespread beehive failures in the United States and the resulting drop in pollination have resulted in an enormous food shortage that threatens the world economy. Orvo is a loner, the father of Eero, his grown-up son. Sinisalo cleverly works in animal rights activist Eero’s controversial blog comments on animal rights and modern man’s flawed relation to nature. However, this is also the novel’s biggest problem, as the blogging starts to weaken the story, of three generations of men in a family. Both the mythic, parallel reality of the bees and the tough-and-tender relationship between father and son are strong indications of Sinisalo’s narrative skill.

Translated by David McDuff

Asko Sahlberg: Häväistyt [Disgraced]

2 February 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Häväistyt

Häväistyt

[Disgraced]

Helsinki: WSOY, 2011. 331 p.

ISBN 978-951-0-38275-2

€ 33, hardback

The tenth novel by Asko Sahlberg (born 1964) is reminiscent of the earlier works of this distinctive author: its principal characters are hardened by experience and lead their lives somewhere in the Finnish countryside during a recent period of the country’s history. The sentences are beautifully constructed, and the pace of the narrative is very slow – sometimes even too slow. The main role is played by a middle-aged man who is running away with a woman and a small boy. What they are running away from for a long time remains a puzzle, as does the question of who they are looking for, a man called The Master. In the flashbacks of the last part of the book all is explained, and the rhythm of the story quickens. Considering the book’s desolate, even fatalistic view of the world, it is slightly surprising that everything eventually turns out as happily as in a fairytale. But perhaps this is Sahlberg’s tribute to his characters, and to all of us human beings, for whom he seems to care a great deal? His novel He (2010) will be published in February in England under the title The Brothers (Peirene Press).

Translated by David McDuff