Tchotchkes for the tsar

11 August 2011 | Reviews

Cornflower and ear of oats: one of the several Fabergé gemstone ornaments now owned by Queen Elizabeth of England (gold, rock crystal, diamonds, enamel, ca 18 cm)

Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm

Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit

[Fabergé’s Finnish masters]

Design: Jukka Aalto/Armadillo Graphics

Helsinki: Tammi, 2011. 271 p., ill.

ISBN 978-951-31-5878-1

€57, hardback

In its online shop, the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg sells a copy of a most delicate, enchanting little nephrite-and-opal lily of the valley that perfectly imitates nature, sitting in a vase made of rock crystal that looks like a glass of water.

These small flowers made of gold and gemstones were manufactured by the jeweller Fabergé a hundred years ago. The lily of the valley was the most frequently used floral motif in the Fabergé workshops – it was the favourite flower of Empress Alexandra (1872–1918), and the imperial family was the the foremost client of the world’s foremost jeweller.

The replica (13.5 centimetres high) is available at the Hermitage as a ‘luxury gift’ for the price of mere $3,300. (N.B. Since we published this review, the ‘luxury gift’ items seem to have disappeared from the Hermitage online shop selection, so we have removed the link. Several Fabergé egg replicas are available though, ranging in price from $200 upwards – link below.)

For those who feel the price is excessive, there is also a rather modestly-priced little bay tree (original: gold, Siberian nephrite, diamonds, amethysts, pearls, citrines, agates and rubies as well as natural feathers, about 30 centimetres tall, featuring a little bird that emerges flapping its wings and singing when a small key is turned) at just $ 219,95. Despite its form, it is classified as one of the famous imperial Easter eggs. (However, as I write, this item is unfortunately sold out…)

In the world of the unfathomably rich, in this instance the imperial family and their circle, it was not just the obvious items – jewellery and ornaments such as the famous Easter eggs, gifts of the family members to each other – that were made of the most precious materials. Naturally also the handles of parasols had to be loaded with diamonds, golden cigarette cases studded with rubies, thermometers made of coloured gold and jewels.

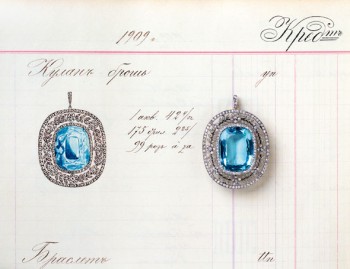

Siberian aquamarine: Albert Holmström's design of 1909. The pendant could also be used as a brooch

The last imperial family of Russia in 1914: from left, Grand Duchesses Olga and Maria, Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra Fyodorovna, Grand Duchess Anastasia, Prince Alexey and Grand Duchess Tatyana. The elder daughters wear necklaces designed by the Finnish designer Alma Pihl

So, St Petersburg of the late 19th and early 20th century offered plenty of work for goldsmiths, clocksmiths, gem-cutters and jewellers. The most famous of them, Karl Fabergé (1847–1920), was a son of the French goldsmith Gustave Favry (Fabergé after he established a business in St Petersburg in the 1840s). Karl was well-trained and well-travelled; as the century changed, he had become the purveyor of fine jewels not only to the Tsar but also to the rulers of Sweden and Norway. He employed more than 500 people.

Fabergé’s first and closest business partner was a Finn: Hiskias Pöntinen (1823–1881, later Pendin) was originally a poor lad from the small town of Mikkeli in eastern Finland, who had come to St Petersburg to look for work. He eventually became a skilful jeweller, and it was he who taught Karl the basics of his trade.

Bolshaya Morskaya 24, 1903: Master August Hollming is in the centre of the photograph

Karl Fabergé worked with 24 goldsmiths, all of whom led their own workshops, and 14 of them were Finnish: he regarded Finns particularly skilled craftsmen as well as honest and reliable employees. The workshops were fully employed by Fabergé, and their production was sold to him exclusively.

Clock with a cockerel: Mme Beatrice Ephrussi, a heiress of the Rothschild family, gave this clock topped with a cockerel (by Mikhail Perkhin of Fabergé) to her brother as an engagement present in 1902

After the outbreak of the Revolution in late 1917 and the murder of the imperial family the following year, Fabergé’s trade was finished, and he left the country. As most of the Finnish craftsmen had no more work either, many of them returned to their now independent homeland.

Among them was jewellery designer Alma Pihl (1888–1976). Alma’s father was the Finnish goldsmith Knut Oskar Pihl, and she was born in Moscow. She began to work in her uncle Albert Holmström’s workshop in St Petersburg and without any formal training became a skilful and remarkable Fabergé designer: a very rare career for a woman.

Alma designed many pieces of jewellery for Emanuel Nobel, the head of the Nobel oil industries, who ordered dozens of brooches, necklaces, bracelets and pendants, all decorated with Alma’s inventive ice-crystal and snowflake designs. Nobel donated them to his business associates and guests all over Europe.

The greatest achievement of her career, however, is the Winter Egg of 1913, a gift from the Tsar to his mother, the dowager Empress Maria Fyodorovna: a staggering 1308 diamonds are set on the eggshell, and a further 1378 in the basket of tiny white anemones inside the egg, made of white quartz. The egg stands on a pedestal of Siberian mountain crystal. Alma’s design was excecuted by her uncle, and it was the most expensive of the 50 imperial Easter eggs made by Fabergé.

The Revolution dispersed them all – the people, the eggs, the jewellery, the clocks and the parasols. The pictures of these priceless luxuries inevitably bring to mind the masses of people in vast old Russia: those who lived in serfdom and exploitation and whose slavery had provided the ruling class with the means to live the lives they chose.

After the Revolution, Alma and her husband had to return to Finland to find work. From 1927 until her retirement in 1951 she held a post as an arts teacher at a secondary school. She never spoke of her flourishing career as a jewellery designer in imperial St Petersburg.

A rare gem: Alma Pihl (1888–1976), Finnish self-made woman whose career at Fabergè was brilliant but short

Alma Pihl’s designs were fresh and new, inspired by Art Nouveau and modernism. It is a pity her career was cut short, writes Ulla Tillander-Godenhielm, an art historian who is herself a Finnish goldsmith of the fourth generation. Her book, which is an edited version of an earlier work – Fabergé, a limited edition published in 2008. Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit concentrates on the craftspeople who designed and manufactured the objects which were realised with the buyers’ unlimited financial resources – an Easter egg might require the work of one man for a whole year.

3,046 diamonds: the Winter Egg (platinum, gold, rock crystal, moonstone, white quartz, nephrite, demantoid granates, ca 14 cm, 1913) was an Easter present from the Tsar to his mother

Tillander-Godenhielm points out that Finnish goldsmithing benefited greatly from the skill and experience of the tradespeople who moved to Finland after the Revolution. The art of jewellery that flourished in St Petersburg and was passed on by apprenticeship became practiced in Finland, too.

Fabergén suomalaiset mestarit is a thoroughly well-researched, handsomely illustrated, beautifully printed work. (An English-language version would probably find an interested readership.) It turns the spotlight on to the numerous anonymous hands that made so many precious objects for emperors and lesser princes – and not just Finnish hands; the book offers a wealth of information about the turbulent years of the late 19th and early 20th century when money was no obstacle, and when the lack of it set the world on fire.

Most of Fabergé’s artefacts disappeared from Russia. Some of the now incredibly expensive and coveted collectors’ items have also now returned to Russia – after the years of Revolution and the Soviet Union. Alma Pihl’s magnificent Winter Egg is now owned by a private collector in Qatar.

Tags: art, cultural history, history

No comments for this entry yet