On the job

10 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

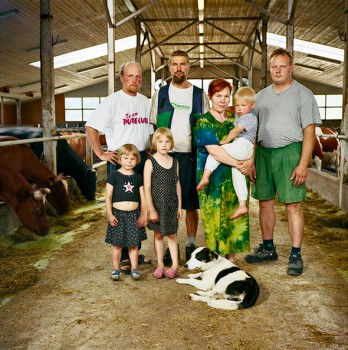

‘I like my pictures to be realistic and truthful, not that I can satisfactorily define what realism is. The real people in my pictures are in their real surroundings, even though they are posing for me. I see this as a series of encounters. The subjects present their “working role” for me, which I record‚’ says photographer Eija Irene Hiltunen. In these extracts she introduces her project and samples of her photography present people at work in contemporary Finland

Extracts from Työn tekijät. Muotokuvia suomalaisesta työstä. / Doing the job. Portraits of Finnish working life by Eija Irene Hiltunen. Texts: Pasi Alametsä. Translations: Joseph White. Layout: Petri Kuokka & Eija Irene Hiltunen (Avain, 2009)

One of the most important aims of my portraits has been to record an image of the times. I chose work as the common denominator because it relates to the social structure on so many levels.

The ‘visual inventory’ of Weimar Germany by the classic photographer August Sander has been the major inspiration for my work. He made a huge impression on me during my student days. He told of the upheavals of his own time through his portraits, as the old class society broke down, and of the time before the Second World War and the birth of modern Germany. Sander beautifully depicted history through the individual, and his portraits have remained as testaments to life during that era.

Another aspect of my series was the comparison of present day work photos with those of Sander’s time. Labour and the work environment have changed but what about the employees themselves? It used to be possible to ‘read’ what work a person was involved in from external appearances.

To what extent can we tell what a worker does from his or her appearance today? How thoroughly do we internalise occupational behaviour, consciously or unconsciously? Different trades and professions have their own behaviour, style of dress, humour and even jargon. Is there such a thing as an occupational image?

During each shoot I asked the subject to adopt a ‘neutral’, peaceful expression, in order to that the viewer would not interpret the subject’s state of mind but that the attention would shift to the occupation and the various details of the subject’s environment.

Sander’s individual portraits together make up a social fabric. So for him, each individual picture was less important than their sequence, their relationship one to another. I have the same idea in my own project.

I have also felt the allure of collecting in my project. Whenever I have completed a new photograph I have placed it among my previous works. So the collection changes with each new picture, as does the significance of the new picture. I have become a collector.

I also interviewed my subjects. My questions concerned the significance to them of work, the good and bad sides of their job, their dream job, the future and their dreams and aspirations. To my surprise, many replied that they would still do their jobs even if their income were assured in other ways. This says a lot about the significance and value a person places on his or her work.

‘I’d say I’m in a good but fairly realistic job. I don’t know any better jobs because I’ve never worked anywhere else, but this suits me so far.

‘The working conditions are quite strenuous sometimes. You can see it and hear it when you’re having a bad day, but when I’ve slept well and the machines are working properly I like the job. And of course it gets hot here inside this suit, although you even get used to that after a while.

‘I might have wondered about the value of this work from time to time, but now I suppose it is quite important, because we supply samples to hospitals too!

‘If I lost this job I’d look for work straight away, even digging ditches. But the future of this operation looks good enough that I don’t expect the work to end just like that. My remedy for reducing unemployment would be to curtail working hours so that overall earnings could be cut by ten percent.

‘I’m not looking for the traditional red summer cottage and a great swarm of kids. I just want to be happy and comfortable with what I do.’

‘If the dream job means doing something that does not feel like work, then I suppose I’m on the right track. Certainly I didn’t have to go far to learn it, since my late father was a fisherman, as was my brother, later on. We all had the same simple idea, though – to put food on peoples’ tables. Nowadays there are only a handful of professional fishermen working in Padasjoki, and the reason has to be the economic uncertainty of the job. You’re constantly at the mercy of the weather and you are never guaranteed a catch. The basic rule is that if someone promises you a certain kind of fish at the end of a week, you can be almost sure it won’t be fresh.

‘The fishmonger’s season begins when the ice recedes and continues till it comes back. I spend the winter making crayfish traps, for myself and for sale, and then smoking the fish I catch for restaurants. Summer is the most hectic time, though. A childhood friend comes to help me out but the working day still stretches round the clock, even at weekends. I get the best kicks on Saturdays when dozens of customers queue up in a good mood for the fresh-caught fish and crayfish, depending on the season. When I began this job people were complaining about why there were no locally caught fish when a nearby EU supported fishing harbour was exporting shells that Finns look down on. Nowadays we can offer more than just frozen supermarket foods and other plastic wrapped products.

‘In the future I intend to concentrate more on developing the business. The Baltic is a competitor with its farmed, unecological trout but it will never be able to beat the Finnish lakes for purity. But because you cannot advertise the arrival of lake fish in advance, in the press, the fishmonger in the market can offer almost the same surprise in the morning that the fisherman had a short while ago during the night.’

‘Being a hospital pastor means discussing questions of sickness, guilt, suffering and death with patients, relatives and staff. Becoming infirm and having to give up so many things often provokes the deepest questions. Sometimes it is very difficult and taxing to dwell on such matters but it is also important, valuable and rewarding.

‘Faith is a gift that can provide hope and confidence when someone must face sickness and approaching death. I cannot give a patient faith. I can only talk with them, help them in their search and pray with them. The clergy too are only ordinary people and they experience their calling in different ways. I also reflected carefully before I dared to believe I had what it takes for this work. There are many expectations associated with the priesthood but I’m still the same person I was before I was ordained. I sometimes have to seek a balance between superhuman expectations and my own ways of working.

‘There is far more work to do in a hospital than I can ever actually do, an enormous number of people who yearn for someone to listen. Patients are ever more infirm and need a great deal of help. They need people here who have time.’

‘We’re a group of friends who have known each other since we were children. At some stage we noticed that we all had a similar interest in making a bigger investment and expanding our activities in other ways. Actually, we could each have made the investment ourselves but it would have been a bigger risk compared with the gain.

‘We each have our own area of responsibility in this joint barn venture, which is mainly for organic farming. There’s financial and bureaucratic management, tending the animals, the arable farming and so on. This way we can be less tied down to our work than we could with a traditional farm, which would be more vulnerable in other ways, too. But financial reasons are not the only ones for organic farming. We think this is only one of the modern the ways to do this job. Besides, the land is not ours, we are borrowing it from our children.

‘Never mind if the bureaucracy has increased and the common EU regulations are stiff and slow to change – the EU does at least offer more opportunities for organic farming than the previous agricultural policy did. One demonstration of this is the current demand for organic produce, which already exceeds the supply. In fact we hope that new policies will help to bring about new companies in the countryside.’

‘I felt the fascination of the new when I first came to Finland. Then I met the day to day reality and I got fed up. Many of my friends left the country. They felt the pay in this field was higher elsewhere and the Finnish weather was depressing. Although I have already spent five years here, I am sure that my future lies elsewhere. My engineering competence is such that I could get a job anywhere in the world. To me, work should be enjoyable and a modern way of earning money, so that I can have a personal life like travel and hobbies. At some later stage in life I will return to my own country. I do intend to visit Finland in the future, too, but mainly in the summer.

‘The best thing here is that the system works. The work atmosphere is relaxed and its easy to push things forward. I also feel I get a good energy here since there is no opposing force in the form of bureaucracy. Colleagues in India share a deeper level of affection for one another, whereas in Finland colleagues are literally that, usually just colleagues. Though I spend eight hours at work I know very little about my workmates but in India that is not the case.

‘Another attraction is that Finland is more absorbent ground for new inventions. By international standards, the country is also very business-friendly, although the taxation side leaves very much to be desired. Here, however, after the constructing and testing it is possible to come up with some great idea and sell it abroad. And it has also been observed here that the new generation wants to work in its own way. I am also certain about what I want for myself. I want to get rich but I also want to spend it all straight away. When you find yourself floating in still water it’s time to start swimming. That’s my motto.’

‘I remember that as a child I knew I’d be a doctor. Specialising as a brain surgeon, however, was more a matter of chance (my childhood friend had a malignant brain tumor)…. I think a good surgeon needs manual dexterity and the ability to make quick decisions, as well as empathy and sensitivity, the latter not always being immediately evident. In my case it’s also a matter of measuring myself and competing against myself.

‘It’s a matter of passion for the job that keeps me together – if I didn’t operate, I wouldn’t feel like me. The most important motive, however, is always the desire to help people in a tangible way.

‘The high standard of Finnish neurosurgery is widely known around the world. The system works efficiently in Finland although the hospitals do not always look high-tech from the outside. But inside the equipment is of top quality. Hospitals don’t compete against each other like they do in some other countries, where the standard is more variable. Patients in Finland are in a class of their own, too. They are usually educated, knowledgeable and demanding but nevertheless sensible and most have realistic expectations. It’s also easy to discuss even difficult matters with them.

‘I aim constantly to improve myself, to progress with my career, and if all goes well become a full professor in neurosurgery. I’m not interested in working abroad because the skills are right here. I also aim to have a long career and to work as long as possible, bearing in mind that one day it will be time to quit this somewhat addictive profession before I have to be ‘carried out’ from the operation theatre.’

Tags: Finnish society, photography

No comments for this entry yet