Green thoughts

Extracts from the novel Kuperat ja koverat (‘Convex and concave’, Otava, 2010)

I decided to go to the Museum of Fine Arts.

After paying for my entrance ticket, I climbed the wide staircase to the first floor. There all I saw were dull paintings, the same heroic seed-sowers and floor-sanders as everywhere else. Why were so many art museums nothing more than collections of frames? Always national heroes making their horses dance, mud-coloured grumblers and overblown historical scenes. There was not a single museum in which a grandfather would not be sitting on a wobbly stool peering over his broken spectacles, interrogating a young man about to set off on his travels, cheeks burning with enthusiasm, behind them the entire village, complete with ear trumpets and balls of wool. The painting’s eternal title would be ‘Interrogation’ and it would be covered with shiny varnish, so that in the end all you would be able to see would be your own face.

I climbed up to the next floor. All I really felt was a pressing need to run away. No Flemish conversation piece acquired in the Habsburg era was able to erase a growing anxiety related to love.

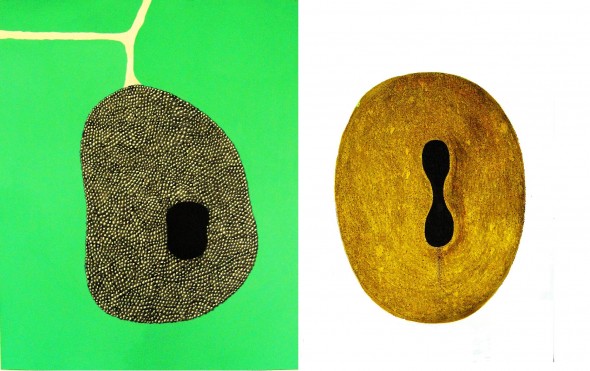

Then all my drowsy senses were awoken by a small painting, hardly the size of a box of chocolate, which I had accidentally stopped in front of. I startled so violently that I didn’t know whether to breathe through my mouth or through my nose. On the label beside the painting I read: Sassetta. Saint Thomas Aquinas at Prayer. Siena. Circa 1400… Aquinoi Szent Tamás… imája…

That small painting immediately turned me into an exclamation mark. I forgot all my needs. The green space of the painting, illuminated from the back, drew me towards it. Saint Thomas looked as if he were floating in his black cloak before the altar, his gaze fastened on an approaching dove, which was pulling a golden ribbon behind it. Particular care had been taken in the painting of the small library on the right-hand side of the painting. Books of all colours lay on their reading stands, closed and open. The centre of the work was made up of an octagonal marble fountain in the monastery garden, painted so that you could sense the coolness and freshness of the water. The finely painted tonsure on Saint Thomas’s head and the halo that surrounded it combined the flat and convex forms. A red cross was embroidered on the altar cloth; it too seemed to float clean and smooth in a painting that was otherwise so still. When I remembered that the Sienese masters also used gold leaf in the base coat of their paintings, I was not surprised at the colours glowing from a distance of five centuries. I had come to Budapest to study in the city’s art school. In a couple of minutes, Sassetta’s painting taught me more than two art schools were to teach me over many years.

Sassetta: Saint Thomas Aquinas at Prayer. Courtesy of Szépmüvészeti Múzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest

But what was that back-lit green that dominated the painting? Household green, said someone inside me. But where did the colour come from? It was not merely chromium oxide. The same green had appeared somewhere before. Then, suddenly, a memory rose up my spinal cord and entered my frontal cavity. I had seen that colour at home, in the barracks. The kitchen table, benches and the matching corner cupboard had been painted exactly the same green as the walls and study of the Benedictine monastery in Sassetta’s painting.

In the museum guide I read the legend of how Thomas Aquinas had asked for fresh herrings to eat shortly before his death. He had eaten them with a smile, retreated to his study, and died. It was believed that the herrings had been poisoned. I did not believe it. A religious hero like that simply could not die of a couple of poisoned herrings, even if he appeared, in Sassetta’s painting, as slender as a bellhop. The painting had all the elements of my childhood kitchen: the green of the table, the herrings, prayer, but raised above intellect and chronology. Righteousness begins wherever it chooses. And after, all in the Bible even hand basins were raised to the level of heavenly coppers.

According to the museum guide, the painting demonstrated the three principles of Thomas Aquinas: wholeness, right relations and purity. It was true. Everything in the painting was whole, and it produced wholeness. When I went on to read that the painting was only a small part of a reredos commissioned by the woolmakers’ guild of Siena, one of the parts of its predella, I wondered whether I should spend the rest of my life traveling the earth to see all the parts of the reredos. But I was in Budapest. I merely ordered myself: lick honey at every opportunity! As I left, I thought how I would describe my experience to Tamás, and in what language? I gazed at the wet, slimy cobblestones as I walked toward Vörösmarty square, where I would catch my tram.

One one of those metal-grey mornings when the trams screeched particularly desperately on both sides of the block of flats, after Tamás’s mother had poured very pale café-au-lait into our handleless cups, Tamás whispered to me that he was in love with some Ildiko and asked me to act as go-between. The Ildiko in question had already heard of me and would like to meet me. Tamás was beside himself with joy.

What should I do now with this café-au-lait, I wondered. And where should I put this thick sandwich with its sausage and all? Certainly not in my mouth. I counted in my mind how many nights still remained before I caught my train home.

My excessive interest in Hungarian folk music, barak pálinka, Bartók’s pentatonic compositions, Mikrokosmos, and the sulphur and mineral richness of the many bathing establishments came to an abrupt end. Tamás explained that Ildiko already knew everything about me, that a foreigner’s support would strengthen their as yet dawning union, that foreign languages and cultures would unite us all. To crown it all he told me of his dream of moving to Australia with his Ildiko. Suddenly I remembered all those hopeless families and children in my home town, families whose intention it was to ‘slip off to Australia next week to pick oranges’. Then I thought that there would soon be four of us sleeping in the big bed. It was big but not boundless. They were going to Australia! My ‘saison hongroise’, as I had characterised that period in various Budapest art cafés, was ending in a silent whimper.

I whimpered and went away, alone. I did not wish anyone to see me off. The eastern railway station expelled from its stomach a plump, dark green train decorated with numerous hammers and sickles; I sat, my lip quivering, in the carriage reserved for foreigners. I was returning home via Moscow. The train was the right one, but felt wrong, as did everything else. The country was wrong, the time was wrong, I was wrong and everything I had imagined was wrong. Why Hungary? Why not, just as well, Sylvania or Vojvodina? In my mind, Budapest shrank to a box, twenty-four by thirty-nine centimeters in size. It was no longer anything but a shell, which contained Sassetta’s painting of precisely the same dimensions.

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: art, contemporary art, novel

No comments for this entry yet