In the detail?

11 December 2009 | Essays, Non-fiction

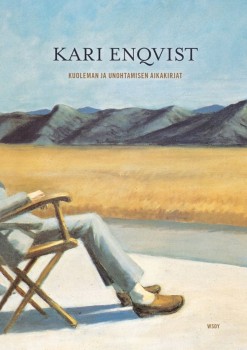

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

Extracts from Kuoleman ja unohtamisen aikakirjat (‘Chronicles of death and oblivion’, WSOY, 2009)

What’s the meaning of life? There are those who seek it in religion, while for others that is the last place to look. The scientist Kari Enqvist ponders why some people, including himself, seem physiologically immune to the lure of faith. Perhaps, he suggests, we should look for significance not in the big picture, but in the marvel of the fleeting moment

As a young boy I must have held religious beliefs. However, I cannot pinpoint exactly when they disappeared. At some point I eventually stopped saying my evening prayers, but I am unable to remember why or when this happened. ‘I was born in a time when the majority of young people had lost faith in God, for the same reason their elders had had it – without knowing why,’ writes the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa in The Book of Disquiet.

When I was reading the Christmas story aloud, I didn’t believe in it. Although I know it cannot be true, I have the feeling that I have in fact never believed in God. My memory does not stretch back as far as my childhood so I cannot say what I thought back then or what kind of child I was. It is as though I have forgotten myself, as though the connection to that little boy is nothing but a construction, a play that in the deepest recesses of my ego I perform for my own gratification. It is for these reasons that my religious Bildungsroman is not a story of relinquishing but of forgetting.

What do I believe in? I believe that the universe is an infinite physical system without goals or objectives of its own. I believe that life on Earth is the result of serendipitous coincidences: our planet happens to be located a suitable distance away from a suitable star. I also believe that life may be found in many of the solar systems in our galaxy, but that intelligent life is a very rare occurrence. At the same time, I know that I do not know these things but that they are beliefs.

I believe that my ego is a process, a capitalist system of molecule factories lacking a concrete core, a five-year plan or a designer that I might call my ‘self’. Its seat is not in only in my brain, rather my whole body takes part in preserving my sense of self. I believe that my experience of my ‘self’ has been stitched together from smaller parts, that I have been many people and that at this very moment different versions of this self are present in my brain, versions that assume prominence according to need and situation. I believe that my will is not free but that my every action, opinion, desire and thought is born of the dance of atoms and molecules that obey the laws of physics and are unguided by the spirit. I believe that the word ‘I’ is a calming lullaby, selected via a process of evolution, a narrative echoing through my consciousness, constructed by my brain to maintain an illusion of continuity and control. I consider religious faith to be a meme that can easily take root in the mind, and I believe that religions do not answer any of the big questions facing the human race but that, for people of faith, religions offer the sense that these problems are being answered.

And I also think that these views do not in any way lessen the value of humanity; they do not lead to nihilism or to the disintegration of ethical values. On the contrary, I believe that regardless of these views – or even because of them – I am on the whole an optimistic, cheerful person, a mild pacifist equipped with a conscience that, compared to that of many people of faith, is highly social.

![]()

It is often said that science answers questions as to what the world is, while religion provides the world with meaning; science tells us how, religion tells us why. In this way, science and religion can be seen to complement one another. In the words of Archbishop Jukka Paarma: ‘Science examines the mystery of the birth of the world and the development of nature and humanity. Faith trusts in the notion that God’s will and His love for human kind is behind everything.’

But what exactly is the meaning that religion gives us? What does the archbishop mean with the words ‘behind everything’? Does he mean that God has created the world and its laws? And what, then, is the significance of this belief? That human life has meaning because God has a plan that He is hiding from us? Isn’t such a manner of thinking merely an example of the simple contention, ‘faith has meaning for me’? But what significance does religion attribute to a loved one’s brain haemorrhage? What meaning can be hidden in my mother’s Alzheimer’s disease? What significance can we read into the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers or the detonation of the atomic bomb above Nagasaki? Once again, people of faith are confronted with a fundamental theistic problem in attempting to establish a correlation between the meaning of God and the significance of individual events.

Indeed, is it not the case that religion cannot offer explanations of the meaning of human life, and that rather, in the face of disasters like the 2004 tsunami, it must accept that these are such incomprehensible events that all prayers simply evaporate on our lips? Why did the Burma Plate slip on Boxing Day 2004? Neither texts deemed to be holy nor the most fervent man of prayer can provide an answer. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that there is no glorious core that can be considered the source of religious meaning. Rather, there is simply a selection of practices that have assumed the stamp of religiosity. At times that stamp can fade away, while at others it can become strengthened through influence of strange coincidences in the surrounding society or human life. It is as though religion were a means-tested stencil for which the logic guiding its use is both fuzzy and passed down through generations.

This is the stance espoused by, amongst others, theologian Ilkka Pyysiäinen, who argues that Lutheran practices provide Finns with a religious prototype. They represent a yardstick by which other religions can be recognised as religions. ‘After this, there is a widening, never-ending sphere of phenomena that resemble religions to a greater or lesser degree. There is no clear boundary between religion and non-religion; there are only phenomena, some of which seem religious, while others do not,’ writes Pyysiäinen.

The small amount of religiosity that I was able to make out in my parents was also largely ritualistic in nature. As a family we never went to church. At Christmas we had a tradition of reading the Christmas story aloud before eating. This was designated my task, and perhaps my parents were hoping to achieve something almost holy as they listened to their only son’s clear voice as he read fluently and with conviction (and over the years with a certain level of theatricality) the familiar story of Emperor Augustus’ decree. As a child, my mother used to read my evening prayers with me, but on the whole it was as though the mere mention of religion was, by some unspoken agreement, deemed improper. The words ‘Lord’, ‘Jesus’ or ‘Christ’ were never used. I believe that my grandmother’s Pentecostalism must have been lurking in the background as an example of the dangers that can be associated with religious language, as though devout religious practice had, thanks to my grandmother, become synonymous with failure, misery and insanity.

It seemed that, over the years, my father’s attitudes towards faith became increasingly indifferent. In this he was very much the product of the age, a century marked by the marginalisation of religious life in industrialised countries. Religion is dying away. It long ago relinquished its place as a guiding beacon for all human life, but its memory lives on in religious practices and rituals. My mother, whom I believe to have been more religious than my father, would sometimes use expressions like ‘such is our lot’, though I am unsure whether there was any deep, religious sentiment behind these words or whether they too were merely part of a ritual of sorts.

Although the focus of faith may be something supernatural, the seat of faith is firmly in the flesh. Though it is often said (in my opinion, erroneously) that thoughts are more than simply the sum total of electrical brain impulses, faith itself remains firmly anchored in the real world and in the laws of physics. It resides in the brain’s neurons and synapses. It rattles along the cortex and flies like a bird over the corpus callosum. It is both electrochemical and molecular biological. In our consciousness, it is physically present in the same way as memories, predilections or next week’s shopping list.

![]()

The analogy to a virus is particularly apt in the case of religion, as faith can be transmitted unwittingly and spontaneously. Unlike purely physiological viruses, religion is a virus of psychological reality or, more specifically, a collection of viruses – or memes.

Memes contain some element that makes them easier to remember. However, we cannot say with any certainty what that element is. Why some books become bestsellers while others are flops is a mystery that every publishing editor would dearly like to solve. One can only surmise that the architecture of our brains, their physiological structure and the ways in which they are filled with memories, opinions and personality traits make us particularly susceptible to certain memes.

Once the faith meme has been transmitted, it already has the power to spread itself. ‘Go ye therefore, and make disciples of all the nations,’ it commands us. As a result of this, sparing no expense, people will get into their cars, drive around ringing the doorbells of complete strangers and asking whether they would like to hear about Jesus. More importantly, however, it commands us to baptise small children and to implant the meme in their minds. Were this not a question of religious faith, such brainwashing would seem wholly immoral, making, for instance, the British scientist and writer Richard Dawkins’ outrage over the religious labelling of children seem perfectly reasonable. Dawkins argues that talk about Christian or Muslim children is grotesque, for what is at stake is not the children’s faith but that of their parents. Still, the faith meme does not listen to such reasoning, but tells us that this is all for the good of the children, that in this way those children will be saved.

Seen from this perspective, faith is a collection of practice that is descended from one generation to the next as a meme. Its longevity is assured by the subsidiary belief, namely that the prize of such ritualistic practice is everlasting life and that to deny this will be punished with eternal suffering. The faith meme carries with it a package saying that faith is always the morally right choice and that non-belief is wrong in the most profound manner. This branding bears painful similarities to Microsoft’s saturation of the computer technology market.

Dawkins famously argues that DNA is selfish; its only concern is to reproduce itself. If we consider the faith meme in the same fashion, the various characteristics of organised religion seem suddenly to fall into place. The faith meme does not jump from one mind to the next as physical matter (doctrine), rather it is transmitted with the help of associated subsidiary beliefs (‘it is right to believe’, ‘faith will be rewarded’) and rituals. If the spread of Christianity had relied solely upon its muddled theology, the church would have dwindled away and become a mere curiosity centuries ago. But the image of the crucifixion or the thought of life after death, a life in which we will be reunited with our loved ones, awakens such powerful physiological reactions within us that faith is transmitted almost by force. All of a sudden we are saved – and who wouldn’t want to go out and spread the good news? It makes no difference that the doctrine itself is incomprehensible and riddled with inconsistencies. Why does a benevolent God allow evil to exist? How can one God become three? Why do we eat God – quite literally – at communion? But what of this! This is why faith has no core to speak of, for ultimately what we are dealing with is simply a group of practices that help the meme to reproduce and that caress and calm the human mind. Faith does not reveal the meaning of life and neither does it provide answers to the why-questions so despised by scientists, but regardless of this it gives us a strong sense that these questions have been answered.

One occasionally hears the contention that, whereas the genes written into our molecules are real, memes are nothing but words and, as such, are every bit as real as the tooth fairy. However, it would be wrong to imagine that memes have no physical being. They inhabit not only the world of the imagination, for thoughts and beliefs are firmly rooted in physical matter. When a belief takes root in our minds, it does so in a very concrete sense. Changes occur in the structure of certain nerve cells; the chemistry of our synapses is altered. The trace of a memory is a physical trace left on our molecules themselves. In fact, memes are probably far more complicated affairs than genes, as an individual belief is not isolated to one single molecule, rather, with all probability, it affects collections of different molecules in different areas of the brain. A meme is therefore a configuration made up of certain molecules. Neither is it necessarily an unambiguous one: different configurations can, in principle, correspond to the same beliefs.

The American philosopher Daniel C. Dennett had argued that, though we cannot identify the physical manifestation of a given meme in different people’s brains, this does mean that the meme itself doesn’t exist. All in all it is a question of how matter is arranged. We might consider memes as intricate mobiles suspended in abstract space, something that can grow or crumble as beliefs change. That being said, certain constellations can be very stable indeed and can latch on to brain matter with relative ease. If, by virtue of their structure, they strive to build similar constellations in other brains, they are behaving like viruses.

The genetic information stored in our DNA is copied from one molecule to the next using, for instance, messenger RNA, which transports the structural drawings of proteins into the cytoplasm around individual cells. Copying and transporting the faith meme is a more complicated affair: the meme causes an electrochemical reaction that is released in the form of preaching and chanting, practices which in the recipient’s brain trigger a construction process resembling the constellation of the original meme.

In the manner of real viruses, the faith virus can be easily transmitted to children whose immune systems have not yet fully developed. Children can be infected at the drop of a hat. The elderly are also in the high-risk group. This too fits the picture.

In theory, viruses can spread easily, but there is always someone who is immune to them. There are a myriad of reasons for this, but of crucial importance is the fact that the reason for their immunity is physiological. Certain parts of that person’s certain cells are structured in such a way that the virus – which is itself nothing more than a longish molecule – cannot latch on to other cells or reproduce itself in the way it is programmed to do (though, naturally, viruses do not have a free will of their own). Alternatively, in some people the body’s defence mechanism is so exceptionally effective that it even produces molecular structures that can neutralise the effects of the virus.

Similarly, the faith virus doesn’t infect everyone. The reasons for this must also be physiological, as recent neuroscientific research suggests. It has been discovered that religious experiences activate certain areas of the brain, leading some neuroscientists to talk of the ‘god module’. And although such a module may not exist, ultimately the phenotype of religion, anything from singing a hymn to reciting the creed is, as has already been ascertained, the expression of brain activity. Non-religious people are therefore people who, because of the architectural make-up of their brains – and therefore, by chance – demonstrate an immunity to the faith virus. In non-religious people, the meme does not trigger any kind of reaction.

Non-religiosity is not a wholly rational position either. People do not become non-religious merely from the weight of the scientific evidence. The unresolved problem of evil or the wrongs of history are not enough to snuff out religious sentiments, though of course they have played a role in developing atheists’ opinions. The philosophical semiotic analysis of religious language is, I assume, of even less significance. For non-religious people, their beliefs do not represent the rational acceptance of a certain doctrine, but what their heart tells them. I cannot reasonably claim that I decided that faith doesn’t have any emotional significance for me. This is simply the way things have happened, thanks to the architectural make-up of my brain. This is the way the molecular machine of my ego has worked: it has created certain chemical changes in my cells and synapses, the manifestations of which we call beliefs. It therefore follows that I do not believe my will has been free in the vulgar sense of the word.

![]()

When the city of Espoo celebrated its 550th anniversary, every home – including mine – received a little booklet from the church entitled Safe: An Espooite’s Faith. The booklet consists of short tales, which are a mix of high literature in the style of the author Bo Carpelan and texts by ordinary people. According to the text on the back cover, their aim is to ‘make the reader think about life and its meaning’. Well, I read it and I thought hard. Little booklets like these provide a far better window into the everyday religious life than the learned and carefully honed epistles of bishops. (An essay fragment by the pastor and writer Matti Paloheimo remembers to mention Wittgenstein, but who among us would not have committed that same sin?)

I had forgotten quite how anguished religious language can be: ‘One day this sorrow and wretchedness will end.’ Many of the texts in the booklet make repeated reference to ‘fear’ and ‘shame’. The assurance of joy and happiness, the climax of most of these texts, sounds like a mantra, just as a tightrope walker crossing a ravine might repeat to himself, ‘I will not fall, I will not fall’. Exaggeration and the obsessive exaltation of mercy speak of a terror that, despite the beatitude of faith, lurks on the edge of consciousness. These writers are at their most sincere as they thank the parish for the sense of security it offers, being able to cuddle up to someone else, protected from the dark, just as our ancestors at the dawn of humanity must have warmed themselves in their caves at night.

For me this booklet did not serve to anchor my everyday life; it made me sad. I felt bad for these people because of the anxieties they experience. They offload this anxiety by writing to one another: once I was lost, living in fear of death, adrift on a churning sea, but now I am safe. But why do people feel the need to repeat these matters ad infinitum? Why did not a single text take joy and love as its starting point? The only exception to this was a text written by an 81-year-old former deacon, offering an uncomplicated account of his working life. I felt almost embarrassed for the editors of the booklet. For once they had the perfect opportunity to reach the vast majority of people in Espoo for whom religious life means very little. And yet I get the sense that, in that respect, they have been unsuccessful. What invigorates those in the hermetic common rooms at the parish, wilts under the broken light of the indifferent outside world into something banal.

These small vignettes about moving from the darkness into the light do not touch me, because I do not live in constant fear of death, I do not feel shame, sorrow or wretchedness. The average day is not perfect and my life includes unfortunate events, but it is not constructed around fear and shame. In this respect, I do not believe that I am in any way exceptional.

![]()

When we look for life’s meaning, we should not look for it in the overall structure but in life’s constituent parts. This is by no means a new observation but one that dates back to Horace when he shouted ‘Carpe Diem’! The words ‘seize the day’ may sound somewhat business oriented, but they can also be understood as a Zen microscope focussing on a single moment in order to separate it into as many elements as possible. This is also what natural science teaches us.

In fact, nature only teaches us if we examine it closely, with as fine a resolution as possible. In this way, nature reveals the mysteries of both matter and the cosmos, thus uncovering the world’s secrets, everything from the atomic bomb to the physiology of proteins. In science, people often say that the devil is in the details. But perhaps something else is hidden there too.

A pragmatist might argue that, if human life is the sum of its experiences, one would be well advised to maximise those experiences. However, this does not refer only to extreme experiences: hang-gliding over the Antarctic, riding on dolphins or travelling to Mars. In this instance, less can often be more. Perhaps it is enough to watch the Sun casting a beam on the wall; an autumn butterfly warming itself there; a cloud high in the summer sky; the wind scattering leaves; a hand holding a book. You need only watch people hurrying along the street to the Market Square; people spilling out of commuter trains at the station; people in far off countries sitting behind their stalls, hopeful and expectant; people that every day, with every step, carry life’s light burden with them. It is enough to listen to the sound of your breath, just enough that you can say to yourself: I am here, I am alive in this moment, this fleeting moment like a diamond between two strikes of the clock. ‘Not altogether bad,’ as the Brits say.

And perhaps it is at moments like this that we can disregard our destiny, forget the past and the future, and feel, if only for a brief moment, the burden of sorrow lift from our shoulders.

Translated by David Hackston

Tags: philosophy, religion, science

No comments for this entry yet