Landscapes of the mind

Issue 2/1986 | Archives online, Fiction, poetry

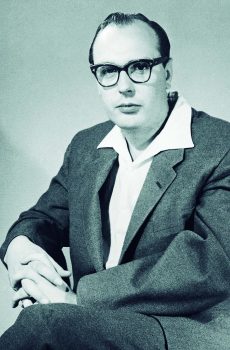

Tuomas Anhava. Photo: Otava

In his book Suomalaisia nykykirjailijoita (‘Contemporary Finnish writers’), Pekka Tarkka describes Tuomas Anhava’s development as a poet as follows: In his first work, Anhava appears as an elegist of death and loneliness; and this classical temperament remains characteristic in his later work. Anhava is a poet of the seasons and the hours of the day, of the ages of man; and his scope is widened by the influence of Japanese and Chinese poetry. As well as his miniature, crystalclear, imagist nature poems, Anhava writes, in his Runoja 1961 (‘Poems 1961’), brilliant didactic poems stressing the power of perception and rebuffing conceptual explanation. The mood in Kuudes kirja (‘The sixth book’, 1966) is of confessionary resignation and intimate subjectivity.

Anhava’s literary inclinations reflect his most important translations, which include William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1959), selections of Japanese tanka poetry (1960, 1970, 1975), Saint John Perse’s Anabasis (1960), a selection from the works of Ezra Pound, published under the title Personae, and selections from the work of the Finland-Swedish poets Gunnar Björling and Bo Carpelan.

![]()

Song of the black

My days must be black,

to make what I write stand out

on the bleached sheets of life,

my rage must be the colour of death, to make my black love stand out,

my nights must be summer white and snow white,

to make my black grief burn far,

since you're grieving and I love you

for your undying grief.

Let the sun's rolled gold gild dunghills,

let the moon's blue milk leak out till it's empty,

we're not short of those.

The obscure black darkness of the cosmic night

glitters on us enough.

From Runoja (1955)

*

The moon in my youth was always thin and pale,

stooping over the stars

or reclining on a cloud, exhausted,

now,

whenever I go out into the evening,

the moon's round,

it's the northern sky's ample navel,

pulled in slightly, slightly off-centre,

but girdled with lard against the cold,

and it never turns its back.

Spring, nightfall, and night’s black hay is ripening –

its myriad wrists are waving and it touches every shape.

When the eye sinks into oblivion, and sleep deepens,

what do we know then that we don’t know?

Once upon a time there wasn't a kingdom that didn't have a king

and he didn't have a head.

This weighed heavily on him.

And he sought out a man who didn't have a spine and placed

his head on the man's shoulders.

The king didn't die. Long live the king.

And he lived happily ever after, and the kingdom

endured for a thousand years and wasn't once upon a time.

From Runoja 1961

*

Absence of wind. Water

in which you see bud by bud

trees clearer than the tree itself.

A civilised glance, an educated voice.

Spends agreeable evenings.

In the company of good friends.

Drinks a glass of wine.

Knows that in the world there’s everything –

the small, the medium-sized and the large.

Not a single living creature

has ever seen him

except before a meeting or after

Trees, wind-collectors around the house,

bird-colonisers, crowned with smoke.

But the forest. . . darkness's only profile,

plains: distance is a sound.

An organising wind.

And the sea, the sky's only portrait.

Darkness insinuates itself silently inside

like fingers along a thigh's inner surface

towards the groin's soft cavity.

That half of the sky, that square

nautical mile, the island and the lights, all these

I’ve arranged here for you,

I’ve laid in supplies of days, nights,

quietness and noise, work and leisure,

I’ve long been laying in supplies of nights,

autumns, winters, springs, springs,

you generate boys (like trees) I too generate,

I make you blossom with my eyes, and with my eyes

I bring a girl out of you,

and you receive all the ages and the passing world.

The water-source stirs.

Like

a child's sleeping face.

I’ve never made a book out of less;

I shall never say more.

No one knows how to hope for his own birth,

and all the rest is theory.

It’s a land of flowing bridges.

Anyone who believes what he sees

is a mystic.

Walk slowly in the dark.

I look at a stone: sixty-eight years

about which no-one has known a thing.

What knowledge is that – that she existed,

that two of her brothers got the reprieve

of an exile to Siberia, 1853, that her sister

was the mother of two illegitimate children

and lived with one of them down the road

and lives there still.

And the birch that grew from their bones has been uprooted

to stop it upsetting the stone.

The snow has sharpened and silenced the landscape

My mind is uncomplicated and patient.

I can see down to the finest detail

the leisurely way the earth is growing trees,

and deep down I hold my breath and go on waiting

for it to sprout grass and the flowers’ brief singing.

From Kuudes kirja (1966)

Translated by Herbert Lomas

No comments for this entry yet