Poetry and Patriotism

Issue 4/1985 | Archives online, Authors, Essays

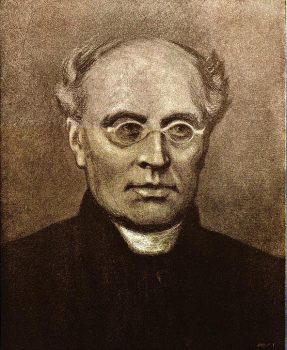

J.L. Runeberg. Painting by Albert Edelfelt. 1893.

Much revered, but little read today, Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804-1877) is famed for his patriotism and glorification of war in a just cause. Yet Finland’s national poet did not write in Finnish, and never heard a shot fired in anger. It is, perhaps, time for a reappraisal.

What did he himself think about becoming a national poet?

Enjoyed it, probably? Who wouldn’t!

Did he write what he wanted and let

the people find their own interpretation?

Or did he write what he believed

the people expected

of a national poet?

Lars Huldén, 1978

It would not be inappropriate to begin a collection of thoughts about Finland’s ‘national poet,’ Johan Ludvig Runeberg, with a biblical text, Second Samuel, 1:25: ‘How are the mighty fallen!’ Runeberg does not own the position he once did, either in the world at large or in Scandinavia; even in his home land his exceptional grandeur has been reduced or, horribile dictu, smiled at.

His once quite substantial English-language popularity began during the Crimean War; a rendering of ‘Sveaborg’ from Fänrik Ståls sägner (‘Tales of Ensign Stål’, 1848-1860) – about the ignominious surrender of the ‘Gibraltar of the North’, the fortress-complex off Helsinki, to the Russians in the Swedish-Russian War of 1808-1809 – appeared in the Illustrated London Times for July 15, 1854; a historical wit might say that it fell into the wrong hands, since, a year later, a combined British-French fleet bombarded the fortress, and inadvertently blew up a few houses in the town. Then, in 1878, Runeberg’s Lyric Songs, Idylls and Epigrams were issued by Kegan Paul, London, and the Cambridge University Press; the translation was made by Eirikr Magnusson, a Cambridge librarian of Icelandic birth, and Edward Henry Palmer, professor – of all things – of Arabic.

The early translators were a mixed lot: ‘Sveaborg’ was done into more-or-less English by one Frans Diderick Wackerbarth, professor of Anglo-Saxon at the Roman Catholic college of Oscott, near Birmingham, an institute better known for its role in the conversion of John Henry – later Cardinal – Newman; Magnusson became a seminal figure in Old Norse studies in Britain; the adventurous Palmer, interpreter-in-chief with the British field force in Egypt, was murdered in a desert ambush.

In 1879, in Boston, Marie Adelaide Brown brought out a translation of Runeberg’s Nadeschda (1841), ‘a poem in nine cantos’; four years later, Wickham Hoffman, war correspondent, sometime secretary of the American legation in St Petersburg and presently Minister Resident in Copenhagen, issued a book called Leisure Hours in Russia, which contained another translation of Nadeschda and four cantos from Ensign Stål. The popularity of Nadeschda – unquestionably the weakest of Runeberg’s long verse-narratives, with its over-picturesque Russian setting, its hostile brothers who are princes, and its eponymous and tiresome ly virtuous heroine, of humble birth, who loves the good brother, and is lusted after by the bad – is hard for us to swallow today, since the poem is so reminiscent of a sentimental opera; indeed, it was turned into just that by Arthur Goring Thomas in 1885. One of its arias, ‘O, my heart is weary,’ was a favorite number in the albums of ‘Songs for the Home’ which ornamented American and British parlorpianos well into the twentieth century; amateur vocalists sang Runeberg, watered down in Julian Sturgis’s libretto, without knowing anything about ‘the eminent Finnish poet’.

A central figure in this Anglo-American enthusiasm for Runeberg was Edmund Gosse, better known as the critic who introduced Ibsen to the English-speaking world: Gosse’s well-informed essay on the poet in the Cornhill Magazine of 1878, reprinted in his Studies in the Literature of Northern Europe (1879), gave Runeberg a genuine literary stature; furthermore, Gosse stayed loyal to Runeberg, and, late in life, still seemed to regard him as the prime poet in the Swedish language. In the introduction to ‘The Poetry of Sweden’ for The Oxford Book of Scandinavian Verse (1925), Gosse wrote that ‘with his gift for direct and transparent expression, Runeberg com bined the accomplishments of a great artist; no one has moulded the Swedish language with more purity and skill than he.’ Oddly, Runeberg’s verse-narrative, King Fjalar (1844), a combination of Sophoclean and Ossianic and Viking elements, cast in fearfully complex meters of

Runeberg’s own devising, was not done fully in English until1904, despite Gosse’s extravagant praise of it; this first rendering, by someone named Bonhoff, and published in Helsinki, was quickly superseded by a new one from the above mentioned Magnusson, printed by the prestigious London house of J.M. Dent.

Oddly, too, Ensign Stål first entered its English own in the twentieth century, although translations of single cantos had been plentiful. A full translation by the poetaster Clement Burbank Shaw (‘A.M., Litt.D., Mus.D.’), with some musical settings and (blurred) reproductions of Johan August Malmström’s and Albert Edelfelt’s illustrations, came out at a small publisher, Stechert’s, in New York (1925), and then, the pinnacle of success, an incomplete version (nine cantos were omitted) appeared at the Princeton University Press in 1938, under the auspices of the American-Scandinavian Foundation and done by the indefatigable Charles Wharton Stork. (Stork had made a whole career out of turning Scandinavian verse and prose, often of the patriotic variety, into English fustian. His translation of Verner von Heidenstam’s epic about the warrior-king, Charles XII, The Charles Men, published by Princeton and the Foundation in 1920, is dedicated by the translator ‘to the memory of those heroes who with honesty of purpose have battled gallantly in lost causes and gone down smiling before many spears.’)

Shaw and Stork worked in response to the popularity the new Republic of Finland (‘plucky little Finland, honest little Finland’) enjoyed in the United States, a popularity culminating in the attention paid to the Winter War, when Stork’s book got a particularly large readership. Actually, though, the two American Ensign-versions had been preceded by one in Finland, made in 1907 by a member of Finland’s distinguished Donner family – Donners can do anything – and published by the old firm of C.W. Edlundh. This effort fell into the hands of a snippy and clever English traveler, Rosalind Travers, leading her to say in her Letters from Finland (1911) that she found Runeberg’s work rather boring, however much she was aware that such authorities as Gosse gave him a very high rank in world literature. Travers’ remarks are interesting, as a harbinger of the reversal in Runeberg’s fortunes which has taken place during the last forty years.

Need it be mentioned that Runeberg was held in even higher esteem in other major cultural realms than in the English American one? To make a long story short: in France, he was mentioned in a breath with Victor Hugo, and Ernest Seillière – the author of La Philosophie de l’imperialisme – thought sufficiently well of him to learn Swedish and translate Nadeschda. (The Hugo comparison, made once again, very recently, by the distinguished Swedish literary scholar, Magnus von Platen, may call to mind André Gide’s response when asked to name the greatest French poet; he said: ‘Victor Hugo – alas!’) In Germany, comparisons with Goethe were not unknown: Rudolf Eucken, himself a Nobel Prize winner, saw in Runeberg’s work an ‘expression of a deep and joyful feeling for life, an affirmation of the innermost center of existence, an unshakeable belief in reason at the utter most basis of things’ (!); in the German language, Runeberg’s works were widely read. For evidence, see Erich Kunze’s Finnische Literatur in deutscher Übersetzung (Helsinki, 1982), where the Runeberg entries occupy fifteen pages – to nine for Zacharias Topelius, three for Aleksis Kivi, and two for Eino Leino. Not surprisingly, Fähnrich Stahls Erzählungen had several printings during the Second World War.

Sphere of influence

As for the praise showered upon Runeberg in the North, we must be content to quote – out of the giant chorus – only one voice, that of the writer Frans G. Bengtsson. Speaking of King Fjalar in 1927, he called it a work ‘without fault from beginning to end’ and ‘incomparably the greatest, most beautiful and most sterling work ever produced in a Nordic tongue.’ Addressing not Runeberg’s literary quality but his impact, Professor Johan Wrede has correctly stated that Ensign Stål is ‘the most influential belletristic work ever to have been written in Swedish;’ and von Platen has said with equal accuracy that ‘no poetic work in the Swedish language realm has been loved as much.’ In Finland, Runeberg’s attraction was such that his work – read and quoted in translation – penetrated the consciousness of the linguistic majority in an instance probably unique in cultural history; what other nation has chosen as its national bard a poet who employed the language of a dwindling minority? The unimpeachably Finnish and not very lettered infantrymen of the 1940s in Väinö Linna’s Unknown Soldier allude to Ensign Ståls verses with ease if not always with accuracy or respect; and some of the most sensitive academic writing on Runeberg has been by Finnish hands, from Lauri Viljanen’s two-volume biography of 1944-48 to Pertti Karkama’s Vapauden muunnelmat (‘Variations of freedom’) of 1982.

But there is no denying that, for our age, Runeberg’s star has descended, although it may not have sunk. Abroad, translations into the major western languages have ceased to appear; at home, the last major biography was Viljanen’s; in Sweden, where Runeberg had been a special favorite of teachers, the last school edition of Ensign Stål appeared in 1957, and we can deduce the age of Swedish friends by their ability (or inability) to quote Runeberg. Similarly, in the United States, the person who recites John Greenleaf Whittier is bound for the old folks’ home. As a curiosity, it may be added that Ensign Stål, intended for Swedish instruction in American public schools by the Augustana Book Concern in 1915, remained in print until the middle 1960s. America has always been behind the cultural times.

It is only Finland itself that persists, albeit not universally, in its residual piety. A mayor of Porvoo, ‘Finland’s Weimar,’ the town whose Runeberg House is a tourist attraction, may bristle at the suggestion that Runeberg is not, after all, a Goethe; and a major Finnish publishing house may quickly sell out a monumental edition of Ensign Stål, with Edelfelt’s illustrations, and have to reprint it. The edition rivalled the old-fashioned family Bible in proportions and crushing weight. Yet even in Finland, which Rosalind Travers once upon a time found littered with Runeberg statues, big and little, as though he were a national saint, the cult has markedly abated; and a gathering devoted to the modernist poet Edith Södergran will get more newspaper attention than a Runeberg symposium.

Threadbare inspiration

What caused the decline? For one thing, certainly, the employment of the patriotic texts of Ensign Stål as an effective instrument of propaganda, stiffening the Finnish will to resist the giant of the east – first in the years of the attempted Tsarist Russification of Finland, around the turn of the century; then in the Civil War of 1918 and its aftermath, where the Whites were equated with the brave defenders of Finnish soil in 1808-1809, and the Reds were supposed to be the tools of the Bolsheviks; and then in the Winter War of 1939-40 and the Continuation War of 1941-44. Yet, however valuable Ensign Stål was as an inspiration in trying times, he became more than a little threadbare from overuse. Such surfeiting on Runeberg’s war poetry, of course, took place mainly in Finland proper, and, to an extent, in neutral and nervous Sweden; everywhere in the West after 1945, and even before, there was a natural skepticism on the part of a sophisticated public toward the very concept of a poet who incorporated the nation’s virtues; witness the hard times the reputations of Kipling (not wholly understood, to be sure) and Longfellow experienced. (The Swedish author and literary scholar Sven Delblanc has wisely observed that Runeberg’s reputation as a representative poet could have much better survived in an eastern bloc nation, where blanket and unquestioning patriotism is required.) Another difficulty for Runeberg, related to that of his excessive exposure in times of Finland’s trials, has been the fact that he was worked to death by schoolmasters; the American Germanist Jeffrey Sammons cogently argues that Schiller (another literary artist easily put to idealistic and inspiratory ends) has been made essentially unreadable for a broad German audience because of force-feeding in the classroom, and the same may be true in Runeberg’s case. Perhaps his disappearance – save for a little lyric poetry – from the curriculum of schools in Sweden, and the reduction of his importance on home ground, will be a boon for him: future adults, if they approach him at all, will be able to approach him with fresh eyes.

Surely, the Runebergian ethos is not a fashionably liberal one, liable to appeal to advocates of permissiveness. His message of self-discipline, of patience, and of self-sacrifice, is currently not very appealing, at least not in the countries where he is likely to be known at all. Also, to societies that pay much lip service to equality, he presents a message of hierarchy: people have their special places, and had better be satisfied with them. Väinö Linna has written that a great many things can be made of Runeberg, but a ‘democrat’ is not one of them; the reader should not be misled by Runeberg’s numerous sympathetic portraits of the disadvantaged. The well-to-do peasants in Elgskyttarne (‘The elk-hunters’, 1838) are kind to beggars, even as Homer’s heads of the household were, and the honest mendicants lament but never chafe at their rôle; Pistol in Julkvällen (‘Christmas Eve’, 1841), maybe the most complex of all Runebergs veterans, is invited to the Major’s estate for the holidays, ‘a brother-in-arms of the owner’, but goes straight to the servants’ hall; Sven Duva is one of those many satisfyingly humble hearts in Runeberg that live and die without complaint. (Yet who among us, Linna asks, would really want to be a Duva, a Paavo?) Conversely, some actors have received the better parts. Dawdling at his well supplied table, Sandels (in the canto of that name in Ensign Stål) behaves with the elegance befitting a Swedish officer, and his men applaud him when at last he gallops to the front; meanwhile they have taken the brunt of the Russian attack. Good Runebergians, their huzzas are not ironic. Even that apparently most democratic of the poems in Ensign Stål, ‘Von Konow and his corporal,’ is about a relationship between master and man; reading it, an American recalls Maxwell Anderson’s and Laurence Stalling’s old play What Price Glory, where Captain Flagg and Sergeant Quirt are genuine equals. But perhaps the hardest of Runebergian thoughts for the contemporary mind to appreciate, let alone embrace, is his glorification of death for the native land, or, simply, battlefield death. We squirm as we read the summary remarks of the girl in ‘The cloud’s brother,’ upon learning that her lover has died a hero: ‘Sweeter far than life I found that love was,/ Sweeter far than love to die as he did’ (Stork’s translation). Such sentiments become all the more distasteful in consideration of the circumstance that Runeberg never served in the military, never heard, a shot fired in anger.

Peasant fiddle?

Turning away from Runeberg’s oeuvre for a moment and examining his life, we seem to discover a figure that is singularly reticent and, in its contradictions, somewhat unattractive. It is disheartening to compare Runeberg’s correspondence to that of his Swedish competitor, Esaias Tegnér. Recently, for the celebration of Tegnér’s two-hundreth birthday, a Stockholm publisher brought out a selection from the Swede’s letters – a bright idea, since the Bishop is one of the North’s great epistolary artists, well-informed, witty, cranky, sharp, insulting, filling every line with a vividness that makes us want to re-explore his excessively florid verse. Runeberg’s letters, on the other hand, even those famous love letters to Emilie Björksten (he destroyed the earlier and perhaps more fiery ones to Mari Nygren, when they were returned to him after her death), are often tiresome: with few literary allusions (Runeberg was not much of a reader), containing little of the sovereign wit his friends so often praised, and politically guarded to the point of pussy-footing. In his correspondence, Runeberg does not show many signs of the valor he demands of his heroes.

There is something cramped here – just as his life was cramped: the childhood in Ostrobothnia (a realm for which he later evinced curiously faint nostalgia), the training at Åbo Academy and the stays as a tutor in the interior of Finland, the removal to a new capital where cultural conditions were pretty well at a pioneer stage, the marriage to an ugly poor relation of an establishment family, the failure to get a university professorship, the years as a teacher in Porvoo (where he achieved a special kind of fame for beating his pupils), the consecration as a pastor (for practical reasons), the hole-and-corner love-affairs, the lack of interest in travel (his patient wife, Fredrika, left an account of his grumpy behavior during an excursion to eastern Finland in the summer of 1838, and he went abroad only once, to Sweden), the passion not only for hunting and fishing but for poisoning foxes. It was in the course of inspecting his baitlines that he had the stroke confining him to the narrowest of prisons, his bed and wheel-chair, for the rest of his days.

The picture we get is of a big fish in a little pond, a school tyrant, a house despot. His eldest son, the sculptor Walter Runeberg, perhaps breathed a sigh of relief, and release, when he got away to Copenhagen and Rome and Paris. Yet, out of fairness to Runeberg, we should add that he may have been what he said he was, in an interview with a Danish visitor shortly before his stroke ‘a peasant fiddle God picks up and plays now and then, and we become the finest Cremona violin, and then He puts us down, and we are a peasant fiddle again.’ Cutting through the false modesty and the boast, we see something else: unlike Tegnér, Runeberg was not an exuberant artist who lived his creative life constantly and intensely, but a plainer man who had sudden bursts of inspiration amidst what was carefully regulated commonplaceness. Or, better, an artist whose emotional activity was hidden inside a shell. Runeberg refused to admit others to his inner world, except in the quick flashes a few of his poems afford, such as ‘Vain wish’ and ‘The single moment.’ Here lies a cause for the striking difference in quality between the handful of masterpieces and the main body of his lyric work. He could not drop his guard very often: this emotional discipline, too, accounts for his devotion to ‘objective’, story-telling forms of verse.

His affection for verse-narrative may also have come from the persistent old-fashionedness of his poetics. In the 1830s, he followed a moribund literary fad with his (brilliant) use of Horatian meters, like Klopstock’s of the 1750s; in the 1840s, he cultivated the Ossianic mode Goethe had briefly used in the 1770s. His single attempt to write a novel was broken off; the surviving chapters point toward the Scottian-humorous vein of The Antiquary. Rather, he cultivated a form Scott had abandoned, the narrative poem in separate cantos ‘romances’, a form destined to die out in the nineteenth century’s course. (It was an artful genre he shared with many of his contemporaries, from Pushkin and Mickiewicz to Tennyson and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer; and he was a master of it – but how we regret that he did not cultivate the gift of prose-writing of which he gave a tantalizing hint in his handful of short stories or sketches, works he regarded as bagatelles.) Lured by the theater, of which he had no practical experience, he wrote a couple of silly farces, some fascinating fragments (one of them, Belägringen (‘The siege’), offering characters almost crazily devoted to the beauty of ‘the courage to die’), and an essentially unperformable Greek tragedy – again, a bow toward the past.

Drama and transfiguration

But Runeberg clearly had the makings of a deft literary psychologist; concealed in the hexameters of ‘The elk-hunters’ and ‘Hanna’ and ‘Christmas Eve’, we can find dramas or, at least, carefully conceived dramatic figures: the hen-pecked Petrus and the ambitious Hedda of the peasant tale, the innocent but intense olfactory eroticism of the tale of the manse, the ‘illicit’ desires – expressed in a glance, as Kim Nilsson has noted, or a misapprehension – in the tale of lonely people at holiday time. Runeberg requires a very attentive reader and, it must be admitted, does not always reward the reader’s close attention. And, old-fashioned as he was, he requires a reader with some training in classical rhetoric, of the very kind he taught so energetically, or even brutally. Rational beings, we may not like the old man in ‘The veteran’ (in Ensign Stål), who enjoys the experience of war; but we have to admire Runeberg’s rhetorical slyness in having him go forward to the churchyard wall, from which (we expect) he will hold a teichoscopy, the account of what the observer on the wall beholds. Instead, the observer himself is absorbed into the spectacle, and becomes – a favorite word of Runeberg – transfigured by the battle. (In his commentary to Ensign Stål, included in the standard edition of Runeberg’s work, Johan Wrede has provided an excellent guide to Runeberg’s rhetorical refinements.) On a more elementary level, we are seduced by Runeberg’s sheer ability to give the colores rhetorici memorable formulation. Who can forget the chiasmus in which Sven Duva is encapsulated: ‘ett dåligt huvud hade han, men hjärtat, det var gott?’ (see p.264). The answer is: no one. Even as Schiller, Runeberg has been a major – the major – provider of quotable winged words for his native tongue.

Finally, another side of Runeberg renders him interesting today, although it sets him at some remove from Schiller’s moral greatness. Backward looking in so many of his literary practices, Runeberg looks forward in his implications to some of the less attractive attitudes of the later nineteenth and the twentieth century. King Fjalar can be taken as a lesson in might-makes-right: the gods, punishing a man of good intentions, merely because he has defied them, are nonetheless to be respected and obeyed. (Subsidiarily, Fjalar may also imply that older and ‘decadent’ societies are properly overcome by young and vital ones.) In Ensign Stål the quasi-holy legend (used by Runeberg in the edifying story of patient Paavo) is turned into a legend of war, with ‘priests’ who approve it and thrive on it (‘The veteran’, ‘Old Lode’), and women who love it (as we are told Lotta Svärd does, ‘She loved the war, whatever it gave’), and officers whose beating of their men is approved (von Fieandt), or who (Lieutenant Zidén) sacrifice their own and their command’s lives for the sake of the ‘transfigured moment’ Runeberg – a primitive mystic? – so much desired. Then there are soldiers who are too stupid to retreat and, in their stupidity, likewise achieve transfiguration. In order to justify the apparent madness of attitude in ‘The Siege’, Runeberg had a biblical verse at hand: First Corinthians 1:27: ‘For God has chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise.’ Sometimes, in his irrationalism and his love of war’s transfigured moment (a moment around which his peaceful idylls are also built, as Tore Wretö has shown), Runeberg appears to arrive at a place not so far away from, say, that of Ernst Jünger, in Der Krieg als inneres Erlebnis. And his admiration of blind loyalty can call to mind the once familiar motto of an elite troop, ‘Meine Ehre heisst Treue.’ (The Finnish people’s ‘loyalty defies death,’ Runeberg wrote, and a little voice may ask: loyal to what?) At his best, Runeberg is a subtle artist; in his undertones, he is also slightly sinister. But are subtlety and a dash of sinisterness qualities we expect, or want, in a national poet?

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by George C. Schoolfield

Life as an outsider - 30 September 1988

Fairy tales of a journalist - 31 March 1984

A portrait of Elmer Diktonius - 30 June 1982

-

About the writer

George C. Schoolfield is professor emeritus of German and Scandinavian literature, Yale University. He is an author, editor and translator of numerous books, among them A Baedeker of Decadence. Charting a Literary Fashion, 1884–1927 (2003) and A History of Finland’s Literature (1998). Schoolfield has written articles and books on Rainer Maria Rilke and on Swedish and Finland-Swedish writers including Selma Lagerlöf, Elmer Diktonius and Edith Södergran.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.