Narcissus in winter

Issue 4/1984 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

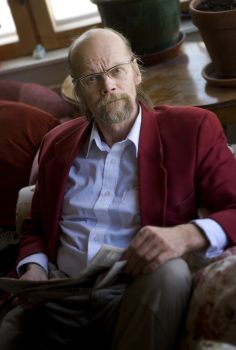

Risto Ahti. Kuva: Harri Hinkka

Poems from Narkissos talvella (‘Narcissus in winter’, 1982). Introduction by Pertti Lassila

Risto Ahti (born 1943) published his first work in 1975. His poetic expression finds form remarkably often in prose poems, and Narkissos talvella is made up exclusively of these. His poems transmute language into a mystical, surreal world, sometimes enigmatic and subjective in the extreme, and at its best strangely suggestive. It is as if Ahti’s world were in a state of constant change, subjected to a relentless process of demolition and rebuilding. The experience of the individual, generally his encounter with truth, is central to many of Ahti’s poems; the inner reality of a person manifests itself as more essential than the outward appearance. Ahti’s poems exhibit a fruitful contradiction: on the one hand, the accuracy with which he uses words and, on the other, the continual shape-changing and lack of definite boundaries of the world they describe. One could say, with one of Ahti’s poems, that the heart is more important than the head. Most unequivocally of all contemporary Finnish poets, Ahti is the champion of the emotions. He is a poetic mystic who experiences visions that go beyond language but who must nevertheless clothe them in language. This paradox generates poems that at their best are brilliant – but it can also result in texts in which the thread of communication between the poet and his readers is threatened or breaks. The problem of knowing is prominent in Narkissos talvella. Its basic form is in the love between two people – certainly a typical choice of subject – communication without words. One of the central mysteries of Ahti’s art is his capacity to approach in words that which lies on the other side of language. This reality cannot be conquered or won by words, but it can be achieved by giving oneself up to it. The poet Ahti seems to operate in no-man’s-land: unlike the philosopher, the poet cannot be silent over that which cannot be spoken.

![]()

Porcelain girl

Even though she's dressed in long pale heavy garments, she seems naked. Her skin's extremely white. She's a china doll that hasn't been enamelled. Life repels her so – I know she's concentrating on death as hard as I'm concentrating on her. My fear ages and enrages me, but I daren't touch her. I daren't! I'm terrified her skin really is ... wax or china. Maybe I'd not be competent to stir her into life with hot longing: her alienation might clang against my cold soul like a bell-clapper.

Moon goddess – if I impregnated her, she'd parturate with things, bones, snow, guns, curdling music, a colonel, a sword of diamond.

Happening

I don't claim nothing happens. When a bird flies back and forth, its nest is shaping up, or a nestling is growing. Waves run ashore, out there a boat's going somewhere. I know its home voyage is already planned. I wait and there they are, the boat's lights in the autumn evening. I think, we go circling around ourselves without ever taking off for anywhere. I think so again at the station as the woman asks: 'Return?' And inadvertently I mutter aloud: 'In reality, though, you can't ever go back.' My voice is so odd, the woman glances up at me, checking softly: 'So – one way?' Agh! a tourists' world. In the train, like a bird flying back and forth, or a boat whose owner has already planned its home voyage, I bump into a stranger: I fly into a wall, I steer onto a rock.

The clock lurks on the wall

The clock lurks on the wall. It looks on like a cold, toothless moon. It lurks and wastes my time. It's a burglar, spreads warmth, takes away cold. Darling! More than the clock of your face I long for the hour-glass of your body! And just as this physical clock depends on our longing, I think fervently of past generations who used to measure time with the movements of their hands.

A rite

A scientist is driving a custom-built car hot after imaginings that contain the cornerstones of his personality. A physical rapture keeps asking: 'To whom – to what can I abandon myself utterly?' The sun burns in his long spindly limbs. A poet in his room is mourning the light of melodies and images. We see dying soldiers everywhere.

Who are the barbarians? The priests and judges? Those who damage reality with queries and alternatives. Those who consider themselves possible, and by making themselves possible create chaos.

Hand me the philosophers' stone, so I can smash the neighbour's living-room window.

Translated by Herbert Lomas

Tags: poetry

No comments for this entry yet