The man and his work

Issue 3/1984 | Archives online, Authors

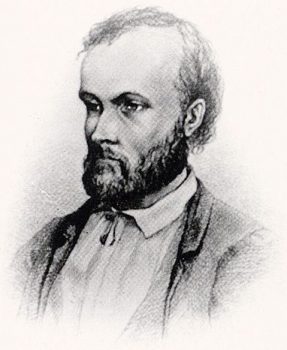

Aleksis Kivi. Drawn in 1873 almost certainly by Albert Edelfelt (1854–1905).

Aleksis Kivi’s Seitsemän veljestä (Seven Brothers, English translation 1929), is the best known and the most beloved in Finland. Its sentences have become part and parcel of the common tongue. Its events are often cited as historical happenings, its characters and their vicissitudes are now permanent national property just as the characters of Shakespeare are for the English, those of Molière for the French, or those of Cervantes for the Spaniards.

Aleksis Kivi’s life (1834–1872) is filled with paradoxes and unanswered questions. How could a village tailor’s son who has acquired only a little learning at home and who managed to graduate from secondary school, after many efforts, only at the age of 23, became an author of the first rank? How could a man who travelled within a radius of only a few dozen miles during his life know the Finnish landscape and the Finnish mind so thoroughly that his novel even today, mutatis mutandis, conveys a true picture of an entire nation? How could he free himself from the spirit and the idealised conception of the art of his own day so completely as to be able to write books sharply at variance with the other literary works of the same era, in which he followed his own path and found fully independent artistic solutions? And how could a book which is, practically speaking, the first Finnish-language novel and which thus springs up as a unique phenomenon from an inadequately cultivated linguistic soil, reach such heights as to become the supreme achievement of all Finnish literature? The enigmatic quality of Kivi’s character is further enhanced by the fact that there exists only one authentic portrait of him, drawn when he already lay dead; that the original manuscript of Seitsemän veljestä is not extant; and that of his letters, only about seventy have been preserved, some only brief notes and most of them dealing with financial arrangements.

The story of Aleksis Kivi’s life is quickly told. The son of a tailor, he was born in Palojoki village in the parish of Nurmijärvi (some 25 miles north of Helsinki) on 10 October 1834. Among his ancestors there were peasants and craftsmen, a few soldiers and a sailor, but not one with any higher education. Aleksis Stenvall – this was Kivi’s real name, which he always used as a private person – spent his childhood years in his home village, receiving his elementary education in the modest village school. He subsequently went to school in Helsinki, being successful at first, then less successful, in his studies. In any case, he matriculated in 1857, and attended, among other courses, classes in literature, history, and folklore at the University of Helsinki. Systematic studies, however, were not to his liking, and the works of Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Ludvig Holberg found their way into his hands much more often than university textbooks. When, in 1860, he won an award from the Finnish Literature Society with Kullervo, a play with a Kalevala theme, the doom of his student life was sealed and the writer’s free career lay open before him.

A Finnish-language author’s career in the Finland of the mid-nineteenth century was extremely uncertain, even hazardous. Swedish was the dominant language of literature and of all cultural life. J. L. Runeberg was the leading poet of the period, and he wrote in Swedish. Some literature in the Finnish language did exist but, with a few exceptions (Kalevala, 1835 and 1849), it generally served the purposes of pedagogic or religious needs. A Finnish novel as such did not exist; it was Kivi who produced it.

The 1860s were Kivi’s most productive period. He was offered an opportunity to live at Charlotta Lönnqvist’s house at Siuntio (about 25 miles west of Helsinki) and to carry on his work under her patronage. The lady in question was not well-to-do, and often the writer shared with her only her debts. Yet her name is recorded in the history of Finnish literature as one of our foremost patrons. The value of her benefaction is heightened by the fact that she knew no Finnish and hence was not able to follow Kivi’s progress. Here again one of the great paradoxes in Kivi’s life is revealed: the greatest of Finnish writers did his life’s work in entirely Swedish surroundings, among people who were unable to read his books.

The later years of Kivi’s life were filled with anxiety. All along, his financial status was poor, and he was afflicted by mental depressions which gradually drove him into insanity. His melancholy was intensified by the fact that his contemporaries did not adequately understand the value of his work: Seitsemän veljestä, which appeared in serial form in 1870, was sharply criticised by Professor August Ahlqvist, the leading literary critic of the period, and its appearance in book form was postponed until 1873. In 1871 Kivi had to enter an asylum, from which he was sent home the following year as an incurable case. In his brother’s lowly cabin, now a museum, he died at Tuusula, near his birthplace, on the last day of the year 1872. His last words, ‘I live’, have assumed a symbolic connotation in the ears of posterity, and although at the time they may have been a plain statement of a fact, they have shown a symbolic truth: in his works Kivi is still, powerfully and intensely, alive.

The greater part of Kivi’s production is drama: plays occupy almost exactly one half of the four volumes of his collected works. The most popular of Finnish comedies came from his pen: Nummisuutarit (‘The heath cobblers’, 1864) and Kihlaus (‘The engagement’, 1866), which, in addition to Seitsemän veljestä, also popular as a play, are regarded as his greatest achievements. They are both exuberant peasant comedies which combine comic and tragic elements. The first relates the unsuccessful courting trip of simple, obstinate Esko, and the second book also concerns the failure of a proposed marriage. (The basic theme must have been close to Kivi’s heart; he never married.) Recently some other plays by Kivi have been gaining popularity as well, and the renaissance-type tragedy Karkurit (‘The deserters’, 1867) has been successfully produced, for example, by the Finnish National Theatre. Also Kivi’s lyric pieces, which his contemporaries considered unfinished and incomplete, have proved more daring and personal than other Finnish poetry of that time.

The position of Seitsemän veljestä as Kivi’s central work has not been shaken by these revaluations. The book is unique for its period and, indeed, in all Finnish literature. The chief characters are seven adolescent, stubborn brothers who, sometime in the early 1800s, flee from society and its obligations (including the necessity of learning to read) into deep woods, build a house there, clearing land for tilling and, as if unnoticed, grow into socially minded responsible citizens in the hard school of solitude and the forest. The book combines realism and romanticism, humour and lyricism, so that even today it can be approached from many different angles. Kivi had not in vain read the writers of the renaissance; something of the spirit and conception of art inherent in the works of Shakespeare and Cervantes can be detected in his novel. In other respects, too, it can be characterised as a ‘renaissance novel’: it was born at the dawn of Finnish literature, during the years of the awakening of Finnish culture, when conscious cultural work in Finland underwent a sudden expansion, gaining dimensions far larger than ever before. Its language is archaic, patinated Finnish, the like of which is no longer written and which for a modern Finnish reader is almost as distant as Shakespearean English is for a modern English reader. For this reason, the genuine tone of Seitsemän veljestä hardly comes through in translation. The only translation currently available, Alex Matson’s of 1929, unfortunately strikes today’s reader as dated.

The hand of a deliberate, careful artist can be traced everywhere in the novel’s structure, the environmental description and the portraiture and juxtaposition of its characters. Kivi rewrote his novel three times, a sign of unusually vigilant and purposeful artistic self-criticism. The characters of the brothers are outlined by the dialogues without explanations: they introduce themselves to the readers through their words and deeds; no background comments by the author are audible. In his narrative Kivi is surprisingly ‘modern’. Scene by scene, the action of the novel advances with careful deliberation; humorous situations, exciting adventures, and lyrical, fantastic stories are interwoven into a balanced, harmonious, and thoroughly original pattern.

There is one contemporary of Kivi’s, whose themes are a far cry from his, but who can be viewed as his distant counterpart: Herman Melville. Kivi springs from an equally unsullied literary scene; his work is as independent and fresh, and he received as little understanding from his contemporaries. The distance from Melville’s vast oceans to Kivi’s vast forests is great, and Kivi’s lyrical imagination and Melville’s symbolism have hardly any thing in common. But each writer demonstrates that an exceptional talent is capable of freeing itself in an astounding manner from its own time and from its conventional standards, and of creating in its art a world of its own which cannot be understood without a knowledge of its hidden laws.

Tags: classics

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Kai Laitinen

On not translating Volter Kilpi - 31 March 1996

A writer and his conscience - 31 March 1993

Builder of words - 31 December 1988

Life and sun: the writer and his time - 30 June 1988

A poet’s perspective - 31 December 1986

-

About the writer

Kai Laitinen (1924–2013) was a literary critic, journalist, author and professor of Finnish literature at Helsinki University. In early 1950s he was the editor of the new literary journal Parnasso. Among his publications are literary history books, essays and a memoir. Laitinen was also the Editor-in-Chief of Books from Finland from 1976 to 1989.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.