They believe in Father Christmas

Issue 4/1982 | Archives online, Authors, Interviews

Mauri Kunnas. Photo: Otava / Katja Lösönen

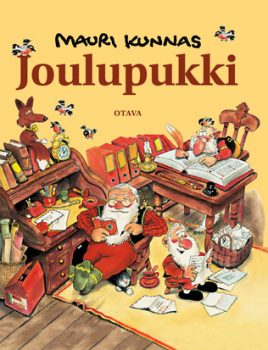

Mauri Kunnas, 32, says he believes in Father Christmas more than ever before. His wife Tarja agrees; she and her husband work together in their studio in Turku on the illustrated children’s books that have won them fame in Finland and abroad. It is easy to believe the truth of the young artists’ protestations: the success of their book Joulupukki, or Santa Claus, must have seemed like a gift from Father Christmas. It appeared in the early autumn of 1981 and was taken to the Frankfurt Book Fair by its publishers, Otava, where it attracted more attention than any Finnish book had done previously. Rights immediately went to ten countries, from Japan to Canada, and four more contracts have since been concluded. Arto Seppälä intervews Mauri and Tarja Kunnas

Mauri Kunnas says he has drawn all his life. He intended to study law, but his sister persuaded him to go to art school instead. Towards the end of his course, short of money, Kunnas began to draw a strip cartoon for a Helsinki evening paper. He progressed to cartoons – but at present his plans for new books keep him too busy to contemplate anything else.

Mauri Kunnas’s first book was Suomalainen tonttukirja (‘The book of Finnish fairies’, 1979). ‘I never thought I would write children’s books until the fairy idea came into my head,’ he says. ‘At that time I was unhappily employed in an advertising agency, and life wasn’t living up to my expectations. I wanted to splash out, try something new. The fairy idea came to me as the result of a chance conversation about the Finnish world of faerie – elves, gnomes, guardian spirits and so on.

‘In 1978 I visited a publisher with about a dozen fairy pictures in my bag,’ says Mauri Kunnas. They were pretty dubious about the whole idea of making a book out of them. I insisted that they’d sell at least 10,000 copies. They told me that children’s books in Finland scarcely ever reach such figures.

‘I made a six-part television series on fairies, and soon afterwards the publishers telephoned me and gave me the go-ahead for the book. As for the sales figures, my estimate was, if anything, a conservative one: the book sold 17,000 copies in Finland.’

Life in the old days

In his next book, Mauri Kunnas described life in a Finnish farmhouse in the mid-nineteenth century. For him, City born and bred, this was a totally strange environment, and the writing and drawing the book demanded a great deal of research on ethnographic details. The book received the title Koiramäen talossa (‘In the Koiramaki household’, 1980) – and its characters were all dogs.

‘I thought the subject would be more interesting if I used animals,’ says Mauri Kunnas. ‘Everything in the book is true, all the details are accurate, but played for laughs, with little jokes to make it move along more easily. Subconsciously I must have been thinking of my childhood companion Donald Duck.’

The second Koiramäki book, Koiramäen lapset kaupungissa (‘The Koiramaki children go to town’) has just been published.

Father Christmas and me

The Father Christmas idea came to Mauri Kunnas soon after the first Koiramaki book was published. ‘I was puzzled that there were so few books about Father Christmas, so I wrote one myself,’ he explains. ‘I didn’t think much about the commercial aspect – although it’s obviously a good thing for a book to appeal to as wide a market as possible.’

‘I didn’t want to write a book about an exclusively Finnish Father Christmas, but neither did I want to be too influenced by American traditions. I tried to use my own conception of Father Christmas and his house, which, as the tradition goes in Finland, is on Korvatunturi mountain, deep in the snows of Lapland. Our research took us to toy factories and libraries, and the book just seemed to grow.’

The popularity of their books shows that the view of the world that Mauri and Tarja Kunnas portray is an appealing one; but they are the first to admit that they do not attempt to describe reality ‘warts and all’. They concede that they avoid unpleasant subjects. ‘If our books are in any way morally educative, it’s purely subconscious on our part. We stress goodness, friendship and humour. But we do hope that our books are informative. We avoid anything that’s forced – we’re looking for spontaneity and space.

Working together

The division of labour in the Kunnas partnership is clear: Mauri draws and Tarja, who is also a primary school teacher, colours. They sit at the same table, working and exchanging ideas.

The division of labour in the Kunnas partnership is clear: Mauri draws and Tarja, who is also a primary school teacher, colours. They sit at the same table, working and exchanging ideas.

‘We don’t skimp on work,’ says Mauri Kunnas. ‘We don’t let anything leave our hands until we are satisfied with it. Three highly illustrated spreads can take the two of us a fortnight to complete. Sometimes we work twelve hours at a stretch, or even more.’

Mauri Kunnas believes that many children’s books in Finland are written too carelessly and too quickly. ‘This may be partly because the readership is so small, but it’s also true to say that there’s far too little competition in Finland. Sales don’t bring in big money, and it’s very few people indeed who can support themselves by writing and illustrating children’s books.

‘There are no short cuts in this business if you want to get on,’ says Mauri Kunnas. ‘Work’s the important thing. Work.’

Translated by Hildi Hawkins

Tags: children's books, picture books

No comments for this entry yet

Leave a comment

Also by Arto Seppälä

On Martti Joenpolvi - 30 June 1986

-

About the writer

Arto Seppälä (b. 1936) is a Finnish author and culture journalist.

© Writers and translators. Anyone wishing to make use of material published on this website should apply to the Editors.