Search results for "ulla-lena lundberg"

The Tollander Prize to Ulla-Lena Lundberg

17 February 2011 | In the news

One of the biggest literary prizes in Finland is the Tollander Prize, awarded annually on 5 February, the birthday of he national poet J.L. Runeberg, by Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland (the Society of Swedish Literature in Finland). The prize is worth €35,000.

The recipient of the 2011 Tollander Prize is Ulla-Lena Lundberg, a versatile writer of novels, short stories, poems and travel essays. ‘She moves freely in different landscapes, times and cultures, finding universality in locality, whether on the island of Kökar in Åland, in Africa or in Siberia’, said the jury.

Written between 1989 and 1995, Lundberg’s fictional trilogy of Leo, Stora världen (‘The big world’) and Allt man kan önska sig (‘Everything one can wish for’), focused on the seafaring history and evolution of shipping in the Finnish Åland islands. Her autobiographical work Sibirien (Siberia’, 1993) has been published in German, Danish and Dutch.

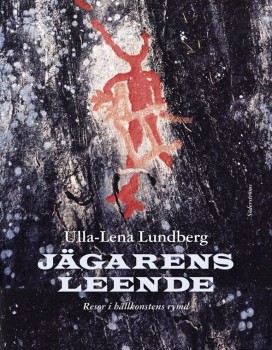

Read the extracts from her latest book, Jägarens leende (‘Smile of the hunter’, 2010), on rock art, reviewed on our pages by Pia Ingström.

Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is [Ice]

1 November 2012 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Is

Is

[Ice]

Helsingfors: Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 364 p.

ISBN 978-951-52-2987-8

€ 23.25, hardback

Finnish translation:

Jää

Helsinki: Teos & Schildts & Söderströms, 2012. 365 p.

Suomennos [Translated by]: Leena Vallisaari

ISBN 978-951-851-475-9

€ 28.40, hardback

Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born on the island of Kökar, Åland, 1947) is already the author of an extensive list of award-winning books, but her new novel Is (‘Ice’) is undoubtedly her most impressive work. It is written in a classic genre, an epic bound by time and place, in which the sensitive portrayal of characters and details takes a strongly ethical direction. Is describes life in a outer archipelago in the late 1940s, where a young priest arrives with his small family. In his calling he is a man devoted to the Word: helpful, friendly, naïvely unsuspecting in his philanthropy. His wife is cast in a different mould: a practical, at times apparently emotionless survivor, who runs a large household single-handed. The couple becomes part of the community of small islands and its harsh living conditions. At times the ice that shuts the island off from the outside world melts into freedom, only to lapse again into a cold that rudely limits human destinies. Barren nature and a community spirit reverting to early Christianity take the measure of each other in the novel’s dramatic events.

Translated by David McDuff

Heartstone

2 December 2010 | Reviews

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

‘Knowledge enhances feeling’ is a motto that runs through the whole of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s oeuvre – both her novels and her travel-writing, covering Åland, Siberia and Africa.

In her trilogy of maritime novels (Leo, Stora världen [‘The wide world’], Allt man kan önska sig [‘All you could wish for’], 1989–1995) she used the form of a family chronicle to depict the development of sea-faring on Åland over the course of a century or so. She gathered her material with historical and anthropological methodology and love of detail. The result was entirely a work of quality fiction, from the consciously old-fashioned rural realism of the first volume to the contradictory postmodern multiplicity of voices in the last – all of it in harmony with the times being depicted.

When Lundberg (born 1947) takes us underground or up onto cliff-faces in her new documentary book, Jägarens leende. Resor i hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’), in order to consider cave- and rock-paintings in various parts of the world, she also reveals a little of the background to this attitude towards life that takes such delight in acquiring knowledge – an attitude that is familiar from many of the protagonists of her novels. More…

Canberra, can you hear me?

31 March 1987 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Johan Bargum. Photo: Irmeli Jung

A short story from Husdjur (‘Pets’, 1986)

Lena called again Sunday morning. I had just gotten up and was annoyed that as usual Hannele hadn’t gone home but was still lying in my bed snoring like a pig. The connection was good, but there was a curious little echo, as if I could hear not only Lena’s voice but also my own in the receiver.

The first thing she said was, ‘How is Hamlet doing?’

She’d started speaking in that affected way even before they’d moved, as if to show us that she’d seen completely through us.

‘Fine,’ I said. ‘How are you?’

‘What is he doing?’

‘Nothing special.’

‘Oh.’

Then she was quiet. She didn’t say anything for a long while.

‘Lena? Hello? Are you there?’

No answer. Suddenly I couldn’t stand it any longer. More…

The rocket

30 September 1988 | Archives online, Fiction, Prose

Raketen (‘The rocket’), a novella from the collection Den segrande Eros (‘Eros triumphant’), 1912. Introduction by George C. Schoolfield

The sun shone straight in through the veranda’s little windows that made the whole ‘villa’ resemble a hothouse. With a sigh, Elsa let the morning paper fall to the floor; she had gotten halfway through the classified ads: ‘Three lads wish to correspond with likeminded lasses.’ ‘If Mr Söders-m does not fetch his effects, left as bond for unpaid rent, within a week, they will be regarded as our property, and his name will be published in toto.’ Now she could stand no more. The air seemed to come from a bakeoven. Listlessly, she watched two flies as they flicked the ceiling paper in their humming dance of love. It seemed as though knives were being thrust into the back of her head; that was the way her sick headaches began. A long walk might stop it, she knew, but she felt too tired.

At last, she was able to make herself get up and open the door for some fresh air. But with the air she got a powerful smell of roasting pork from the baker’s villa; the yells of the children playing cops and robbers up on the rock were doubled in force. A nasty stabbing sensation began in Elsa ears. And so she decided to take a walk after all, but only to the steamboat jetty. More…

The Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012

13 December 2012 | In the news

Ulla-Lena Lundberg. Photo: Cata Portin

The winner of the 29th Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, worth €30,000, is Ulla-Lena Lundberg for her novel Is (‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms), Finnish translation Jää (Teos & Schildts & Söderströms). The prize was awarded on 4 December.

The winning novel – set in a young priest’s family in the Åland archipelago – was selected by Tarja Halonen, President of Finland between 2000 and 2012, from a shortlist of six.

In her award speech she said that she had read Lundberg’s novel as ‘purely fictive’, and that it was only later that she had heard that it was based on the history of the writer’s own family; ‘I fell in love with the book as a book. Lundberg’s language is in some inexplicable way ageless. The book depicts the islanders’ lives in the years of post-war austerity. Pastor Petter Kummel is, I believe, almost the symbol of the age of the new peace, an optimist who believes in goodness, but who needs others to put his visions into practice, above all his wife Mona.’

Author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg (born 1947) has since 1962 written novels, short stories, radio plays and non-fiction books: here you will find extracts from her Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010). Among her novels is a trilogy (1989–1995) set in her native Åland islands, which lie midway between Finland and Sweden. Her books have been translated into five languages.

Appointed by the Finnish Book Foundation, the prize jury (researcher Janna Kantola, teacher of Finnish Riitta Kulmanen and film producer Lasse Saarinen) shortlisted the following novels: Maihinnousu (‘The landing’, Like) by Riikka Ala-Harja, Popula (Otava) by Pirjo Hassinen, Dora, Dora (Otava) by Heidi Köngäs, Nälkävuosi (‘The year of hunger’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen and Mr. Smith (WSOY) by Juha Seppälä.

New from the archives

29 January 2015 | This 'n' that

Ulla-Lena Lundberg

Low-lying, sea-girt pieces of rock strewn across the sea midway between Finland and Sweden, the Åland Islands – known in Finnish as Ahvenanmaa – are a world unto themselves. In mind and spirit they are separate from both Finland (to which they technically belong) and Sweden, giving their inhabitants, writers included, a fascinating outsider status.

This week’s archive find, an extract from Leo, the first volume of Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s trilogy set in 19th-century Åland, offers a compelling portrait of the potent mix of cosmopolitanism and (literal) isolation of the islands’ seafaring community, in which the men sail the seas and the women stay at home.

Born on Åland in 1947, Lundberg is a writer of novels, short stories, poems and other essays; her work, she says, derives from her habit of sitting under the table as a small child and listening to what the grown-ups said. She received the Finlandia Prize in 2012 for her novel Is [‘Ice’], and the Tollander Prize in 2011.

*

The digitisation of Books from Finland continues apace, with a total of 354 articles and book extracts made available online so far. Each week, we bring a newly digitised text to your attention.

Human destinies

7 February 2014 | Articles, Non-fiction

To what extent does a ‘historical novel’ have to lean on facts to become best-sellers? Two new novels from 2013 examined

When Helsingin Sanomat, Finland’s largest newspaper, asked its readers and critics in 2013 to list the ten best novels of the 2000s, the result was a surprisingly unanimous victory for the historical novel.

Both groups listed as their top choices – in the very same order – the following books: Sofi Oksanen: Puhdistus (English translation Purge; WSOY, 2008), Ulla-Lena Lundberg: Is (Finnish translation Jää, ‘Ice’, Schildts & Söderströms, 2012) and Kjell Westö: Där vi en gång gått (Finnish translation Missä kuljimme kerran; ‘Where we once walked‘, Söderströms, 2006).

What kind of historical novel wins over a large readership today, and conversely, why don’t all of the many well-received novels set in the past become bestsellers? More…

The books that sold

21 February 2013 | In the news

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s novel Is (‘Ice’), also turned out to be the winner of the ‘Shadow Finlandia’ prize of the Academic Bookstore in Helsinki. The novel, set on the Åland islands in postwar years, was simultaneously published in Finnish as Jää. This book trade prize is awarded to the best-selling title of the six finalists on the Finlandia Prize list.

The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Fiction 2012, Ulla-Lena Lundberg’s novel Is (‘Ice’), also turned out to be the winner of the ‘Shadow Finlandia’ prize of the Academic Bookstore in Helsinki. The novel, set on the Åland islands in postwar years, was simultaneously published in Finnish as Jää. This book trade prize is awarded to the best-selling title of the six finalists on the Finlandia Prize list.

The best-selling Finnish debut work in the Academic Bookstore was Nälkävuosi (‘The hunger year’, Siltala) by Aki Ollikainen.

Also number one on the December list of best-selling Finnish fiction titles compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association was Lundberg’s novel – in its Finnish translation; the original Swedish-language book came number ten on the same list.

Number two was Sofi Oksanen’s new novel set in Estonia, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’, Like), and number three the hilarious graphic story, Piitles. Tarina erään rockbändin alkutaipaleesta (‘Beatles. The story of the first stage of a rock band’, Otava), by Mauri Kunnas who has written and illustrated dozens of children’s books.

In first and second place on the translated fiction list were J.K. Rowling and J.R.R. Tolkien (The Casual Vacancy, The Hobbit or There and Back Again).

Children chose Finnish books in December – or rather their parents did, buying them as Christmas presents – for the first four places were taken by popular writers such as Sinikka and Tiina Nopola, Aino Havukainen & Sami Toivonen, Mauri Kunnas (Piitles is for mums and dads, not kids!) and Timo Parvela.

On the non-fiction list there was a selection of world record books, cookbooks and biographies – not unusual, considering the season – but number one was Kaiken käsikirja (‘Handbook of everything’) by astronomer and popular writer Esko Valtaoja. A present for all occasions, then?

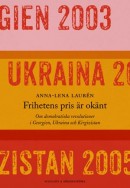

Anna-Lena Laurén: Frihetens pris är okänt. Om demokratiska revolutioner i Georgien, Ukraina och Kirgizistan [The price of freedom is unknown: On democratic revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan]

22 November 2013 | Mini reviews, Reviews

Frihetens pris är okänt. Om demokratiska revolutioner i Georgien, Ukraina och Kirgizistan

Frihetens pris är okänt. Om demokratiska revolutioner i Georgien, Ukraina och Kirgizistan

[The price of freedom is unknown: On democratic revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan]

Helsinki: Schildts & Söderströms, 2013. 212 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-523-227-4

€25, paperback

Finnish edition:

Kuinka kallis vapaus – värivallankumouksista Georgiassa, Ukrainassa ja Kirgisiassa

Suomentanut [Translated into Finnish by] Liisa Ryömä

Helsinki: Teos, 2013. 219 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-951-851-473-5

€28.40, paperback

Anna-Lena Laurén (born 1976) is an award-winning Finland-Swedish journalist, author and Moscow-based foreign correspondent. In this volume of reportage, she investigates three post-Soviet states after their ‘democratic revolutions’, which took place between 2003 and 2005. Georgia, Ukraine and Kyrgyzstan differ from one another in many respects. Georgia has made the most progress along the road to democracy, but even it remains an authoritarian state. Ukraine is plagued by corruption; impoverished Kyrgyzstan – culturally and linguistically divided, like Ukraine – is relatively free, but corruption is rife. For good or ill, these countries are overshadowed by their former ruling power, the present-day nation of Russia. Anna-Lena Laurén has listened with a keen ear to politicians, intellectuals, farmers and workers, as well as members of minority groups. She is well-versed in the history and current situation of these countries and portrays people’s everyday lives with empathy while spotting the green shoots of democracy in among the difficulties.

Translated by Ruth Urbom

What Finland read in February

28 March 2013 | In the news

Artist and painter Hannu Väisänen (born 1951) began writing an autobiographical series of novels in 2004. Born in the northern town of Oulu, he colourfully described his somewhat bleak childhood in a family of five children headed by a widowed soldier father. His fourth novel, Taivaanvartijat (‘The guardians of heaven’, Otava), is number one on the February list of best-selling Finnish fiction titles compiled by the Finnish Booksellers’ Association.

Number two is former number one, the Finlandia Prize -winning novel Is (‘Ice’, in Finnish Jää; also to be published in English, possibly later this year) by Ulla-Lena Lundberg.

The latest comic book by Pertti Jarla about the inhabitants of Fingerpori (‘Fingerborg’, Arktinen Banaani), Fingerpori 6, was number three.

In first and second place on the translated fiction list were Stephen King – (11/22/63) and J.R.R. Tolkien (The Hobbit or There and Back Again).

At the top of the non-fiction list is, for the second time, Kaiken käsikirja (‘Handbook of everything’, Ursa) by astronomer and popular writer Esko Valtaoja. In these hard times Finns seems also to be interested in economics, so number two was Talous ja utopia (‘Economics and utopia’, Docendo) by Sixten Korkman, professor and specialist in international and national economics.

How much did Finland read?

30 January 2014 | In the news

The book year 2013 showed an overall decrease – again: now for the fifth time – in book sales: 2.3 per cent less than in 2012. Fiction for adults and children as well as non-fiction sold 3–5 per cent less, whereas textbooks sold 4 per cent more, as did paperbacks, 2 per cent. The results were published by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association on 28 January.

The book year 2013 showed an overall decrease – again: now for the fifth time – in book sales: 2.3 per cent less than in 2012. Fiction for adults and children as well as non-fiction sold 3–5 per cent less, whereas textbooks sold 4 per cent more, as did paperbacks, 2 per cent. The results were published by the Finnish Book Publishers’ Association on 28 January.

The overall best-seller on the Finnish fiction list in 2013 was Me, Keisarinna (‘We, tsarina’, Otava), a novel about Catherine the Great by Laila Hirvisaari. Hirvisaari is a queen of editions with her historical novels mainly focusing on women’s lives and Karelia: her 40 novels have sold four million copies.

However, her latest book sold less well than usual, with 62,800 copies. This was much less than the two best-selling novels of 2012: both the Finlandia Prize winner, Is, Jää (‘Ice’) by Ulla-Lena Lundberg, and the latest book by Sofi Oksanen, Kun kyyhkyset katosivat (‘When the doves disappeared’), sold more than 100,000 copies.

The winner of the 2013 Finlandia Prize for Fiction, Riikka Pelo’s Jokapäiväinen elämämme (‘Our everyday life’, Teos) sold 45,300 copies and was at fourth place on the list. Pauliina Rauhala’s first novel, Taivaslaulu (‘Heaven song’, Gummerus), about the problems of a young couple within a religious revivalist movement that bans family planning was, slightly surprisingly, number nine with almost 30,000 copies.

The best-selling translated fiction list was – not surprisingly – dominated by crime literature: number one was Dan Brown’s Inferno, with 60,400 copies.

Number one on the non-fiction list was, also not surprisingly, Guinness World Records with 35,700 copies. Next came a biography of Nokia man Jorma Ollila. The winner of the Finlandia Prize for Non-Fiction, Murtuneet mielet (‘Broken minds’, WSOY), sold 22,600 copies and was number seven on the list.

Eight books by the illustrator and comics writer Mauri Kunnas featured on the list of best-selling books for children and young people, with 105,000 copies sold. At 19th place was an Angry Birds book by Rovio Enterntainment. The winner of the Finlandia Junior Prize, Poika joka menetti muistinsa (‘The boy who lost his memory’, Otava), was at fifth place.

Kunnas was also number one on the Finnish comic books list – with his version of a 1960s rock band suspiciously reminiscent of the Rolling Stones – which added 12,400 copies to the figure of 105,000.

The best-selling e-book turned was a Fingerpori series comic book by Pertti Jarla: 13,700 copies. The sales of e-books are still very modest in Finland, despite the fact that the number of ten best-selling e-books, 87,000, grew from 2012 by 35,000 copies.

The cold fact is that Finns are buying fewer printed books. What can be done? Writing and publishing better and/or more interesting books and selling them more efficiently? Or is this just something we will have to accept in an era when books will have less and less significance in our lives?

Stories in the stone

2 December 2010 | Extracts, Non-fiction

Extracts from Jägarens leende. Resor in hällkonstens rymd (‘Smile of the hunter. Travels in the space of rock art’, Söderströms, 2010)

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘Why do some people choose to expend what is often a great deal of effort hammering images in the bedrock itself, while others conjure up, in the blink of an eye, brilliantly radiant pictures on a rock-face that was empty yesterday but is now peopled by mythological animals, spirits and shamans?

‘I think about this often – I who love painting but who still chose a career that involves me sitting and hammering away, day in and day out, like a true rock-carver,’ writes author and ethnologist Ulla-Lena Lundberg in her new book on the art of the primeval man

When the children of Israel went into Babylonian captivity, hanging up their harps on the willow-trees and weeping as they remembered Zion, my sister and I were already sitting by the rivers of Babylon. We knew how they felt. Our father was dead and we had been sent away from our home. We sat there clinging to each other, or rather I was the one clinging to Gunilla, and she had to try to rouse herself and find something for us to do, to give us something else to think about. More…